But lets start from the top. What is a minimum income? Currently, there are two main models for a minimum income - the universal basic income (UBI), and the negative income tax (NIT). They're similar, but also slightly different in how they're implemented. A negative income tax basically gives you money to top you up to a certain among, after which point you start getting taxed. However, this has problems, such as how often would your income be evaluated? If it was only annually, then someone could be unemployed for a year or more before they receive their minimum income payments. More frequently would be better, but would also be more challenging to implement. The other alternative is a universal basic income, which gives every adult a monthly cheque regardless of income. At the end of the year, this would be included in taxable income. This is also problematic: primarily because of the high costs up front, plus the optics of giving everyone a cheque, including those who do not need it.

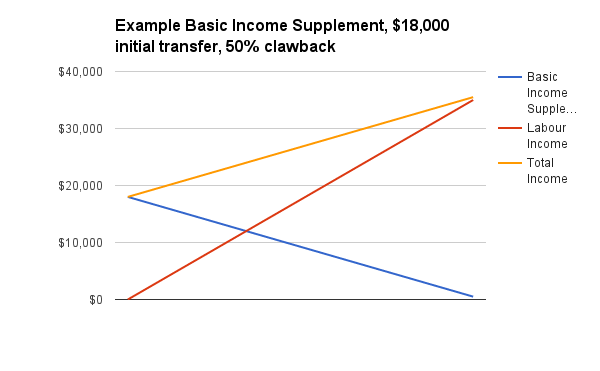

One of the first questions people have when I mention a minimum income is what's to stop people from working. Well, the current model of welfare doesn't incentivize work - once you earn over a certain threshold, you are no longer eligible. So there's a hard cut off before which point there's no reason to work. Under a minimum income model, you are not penalized for working more, and instead the supplement is taxed at a certain rate (often suggested to be 50% for every dollar you earn), up until a certain amount. So there's always an incentive to work (as shown below).

When the data from Dauphin was analyzed, Dr Forget's found that while there was a slight decrease in people working, it was among those in late high-school who stayed in school to graduate (rather than picking up part-time employment), and parents who stayed home to be with their children. In fact, the biggest benefit is to allow you to take risks that may not pay off immediately, such as furthering your education, obtaining more training or qualifications, or setting up your own business. Forget found that many young people stayed in school, and Grade 12 enrollment increased while the project was active. Oxfam recently implemented a mincome project in eight villages in India, and compared the results to 12 control villages. They found that the experiment had huge impacts on the community, with "improvements in child nutrition, child and adult health, schooling attendance and performance, sanitation, economic activity and earned incomes, and the socio-economic status of women, the elderly and the disabled." (Standing, 2014) In fact, they saw a shift from from casual wage labour to own-account farming and small-scale business, which helps people move out of poverty. Perhaps the most challenging aspect of the above is the stigma and mindset associated with giving everyone "free money." While we can acknowledge that people can be trapped in poverty, there's less of an onus on helping people out of poverty. A minimum income helps people plan for the future, helps absorb unforeseen circumstances and situations, and can allow for people to take risks.

Fascinatingly, there are people on both sides of the aisle who are interested. On the one hand, you have those who are socially liberal recognizing the benefits of giving everyone a guaranteed income for the reasons outlined above. On the other side of the political spectrum, you have fiscal conservatives recognizing that this could save money by eliminating social assistance programs and reducing bureaucracy. However, we need to pilot test it and collect better data to evaluate how sustainable or enforceable such a policy would be. Nationally, this would be very difficult to implement. However, the benefits, which could range from a better educated workforce to lower hospital visits, could result in massive savings overall.

With changing global economies, and a large proportion of the population in precarious employment, there's been a renewed interest in a minimum income guarantee. In Canada, estimates for the number in precarious employment (contract work, temporary short term work) ranges, but estimates suggest around 20% of people in Toronto and Ontario are precariously employed. As we gain a deeper understanding on poverty and how it can be passed down between generations, our current approach is evidently not sustainable or successful. This isn't a silver bullet solution to poverty by any stretch. Income is one part of it, but there are also issues around discrimination and stigmatization, lack of contacts to obtain experience and jobs, and other factors that feed into it. However, this is a start, and evaluating whether it works with good data is the only way to know if this is the way of the future.

.

= This is so fundamentally accurate.

Economists know this, politicians know this, wethepeople know this.

Yet psycho politicians continue to use the lower-incomed amongst us as economic pressure valves. When they've FUBARed the economy - which is often - they simply give out less welfare benefits to balance their books. And hope that many will die from starvation which will amount to yet more savings (which they'll give to their pals the banksters to boost their directors' bonuses....)

.

.

"Nationally, this would be very difficult to implement. "

.

= Oh come off it, Atif!!

Who da fek told you to write that?

Have you actually filled in any income tax forms yet or are you still so wet behind the ears that you've still got that protracted delight in store for you?

.

Similarly, have you any idea how eyewateringly complex are all the banksters' instruments and systems for making profits/evading tax as they manipulate fiat money into incredible contortions as they move their deals around the globe?? They couldn't give govts a few tips on running a new economic system?

.

(Cf. tax revenue collection systems above).

.

.

"[the plan]...gives every adult a monthly cheque regardless of income. At the end of the year, this would be included in taxable income. This is also problematic: primarily because of the high costs up front, plus the optics of giving everyone a cheque, including those who do not need it. "

= Fek again, Atif!

Are you in need of remedial classes?

Do you know how many public $billions/trillions even are being wasted on such hare-brained schemes as 'affordable care for all', the NHS's endless 'reforms', the UK's 'Universal Credit' wheeze, US food stamps, 'Welfare to Work', 'Workfare', joined-up information/IT systems that ALWAYS fail, investigating and assessing those who cannot work, and so on and so on...?? (Most of which profits the big corps charged with implementing such FUBARs).

And 'optics'?? Let's have some plain English here!

Seems like you've already spent too long around those govt spin doctors with their dodgy jargon. Clearly they're telling you to nix the whole idea before it 'grows legs'.

Jiminy, Atif! Do you have any idea what sort of psychopathic crowd you're running with these days!

.

I can assure you Atif, that if EVERYONE has $18k deposited in their bank account in monthly installments there will be ZERO "optics" involved! People aren't going to give a flying fig what their neighbors are getting as long as they've got theirs.

.

And, of course, this income is taxable if the recipient earns over and above the $18k.

.

You do know the extremely low cost of mass BACS type transfers, don't you?

.

Plus, and here's the biggie, the army of poor people in receipt of $18k/yr each will actually be able to BUY MORE.

On which purchases they will PAY TAX!

Which, as you may know, means that the tax money actually goes back into the public treasury.

.

And, here's a cracking bonus, because more people are able to spend more money on goods and services...it will mean that more employees are needed!! And the newly enriched might just be able to better their lot! Thus adding even MOAR to the public commonwealth in oh-so-many-ways!

(Doesn't all that make you feel warmfuzzy all over, Atif? It does me...)

.

.

Did I make all that simple enough for you, Atif?