Isn't that the conventional wisdom? Whenever a person gets old, or even "old," they complain about the growing rapidity of time. Weeks seem shorter. The endless summers of childhood become one or two sweaty months of having to wear work clothes in 90 degree weather. The holidays come and go before you realize it. Time used to go slow enough that you could run out of things to do and actually get bored. Now, most people complain about not having the time to do the stuff they claim to want but never really pursue.

As you all know, I'm committed to living well over living long. I'll take a long life, but I'm more interested in compressing my morbidity—the end-of-life inability to take care of oneself and appreciate the good things this world offers. If a long life means being hooked up to life support for the last ten years, I'll pass.

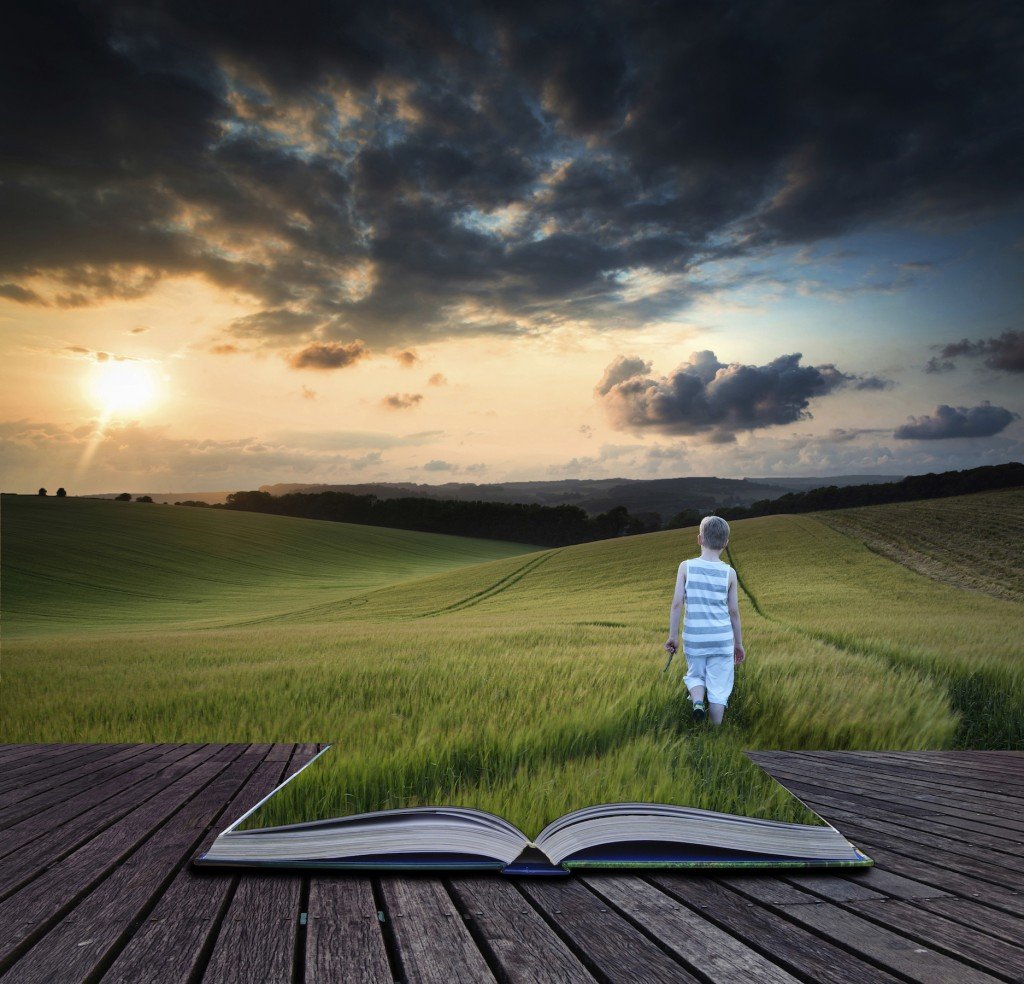

An important piece of living well as you age that most never consider is taking advantage of the fact that time perception is entirely a construction of the brain. By slowing down the perceived passage of time, you seemingly have more of it and live longer—and better.

Stop thinking of time as money (even if it is).

Increasing value breeds scarcity, even if it's just the perception of scarcity. So when we think of our time as money, our time gets more valuable—and more scarce. And instead of packing our schedules full of interesting experiences, we work longer to make more money. Reading for pleasure becomes wasteful. Sitting down to dinner with the family is an extravagance you have trouble justifying. The time we do take as leisure becomes more harried with worry we could be doing more.

Embrace novelty.

Time passes slowly for children in part because everything they're seeing, doing, experiencing, smelling, hearing, and tasting is new and takes up a larger portion of their memory. They've only just arrived on this plane of existence and their brains are working overtime to process an abundance of novelty. Each experience is fascinating.

Compare that with the average adult working a 9-5. They get up at the same time every morning. They eat the same breakfast. They take the same route to work. They sit down at their desk and perform the same tasks they performed yesterday and every day prior. Everything is routine. The brain doesn't have to work to process any new information or remember the specifics. It's the same thing day in, day out. They can't really remember what they did one, two, three days ago—not because they're going senile at age 33 but because every day is the same and the brain literally doesn't see the need to retain the memory of each. This is precisely when days slip into months into years and before you know it you're coming up on 40 and The Simpsons is on season 26 and that new Star Wars movie is already out and is it really 2016 in less than a week?

One researcher devised a cool method to test this concept in the lab. He showed people a slideshow of identical images of a brown shoe interspersed with the occasional "oddball" image of a flower. Though the flower image spent the same amount of time on the screen as each individual shoe image the slideshow, participants swore it remained onscreen for much longer than the others. Other researchers have confirmed the "oddball" effect; time lengthens in the presence of novelty.

It turns out that "with repeated presentations of a stimulus, a sharpened representation or a more efficient encoding is achieved in the neural network that codes for the object, affording lower metabolic costs." In other words, doing the same routine every day barely registers in the brain. You don't notice it. You don't remember doing it. Thus, entire days are lost.

Novelty can be objectively exciting things like going to a drum circle at the beach, skydiving, rock climbing, or taking a salsa class. But small changes work, too. Take a strange route to work. Take your bike to work. Try a new restaurant every week instead of eating at the same diner.

Work smarter.

We're more productive, sure. We have dozens of high-tech tools to help us multitask and communicate with anyone at a moment's notice. We can find the most arcane bit of knowledge in under a minute. It's all saving us time, right?

Except we're working more than ever. And when we're not working, we're thinking about work. Or we're turning our leisure time into work by trying to "optimize" it. We tell ourselves we're saving time, but we're really chasing the optimization dragon. Few ever condense work to a few productive hours each day and spend the bulk of their time enjoying the moment. It just doesn't happen. Instead, we just use our productivity gains to spend even more time working.

Avoid multitasking. Stick to the task at hand. Don't go flitting off into Wikipedia. Don't have so many tabs open that the favicons disappear. Multitasking only makes time perception speed up, and it doesn't even improve productivity.

Check email twice a day. If email's a big part of your day, do not keep the inbox open on your browser. You're going to look at it every ten minutes, dreading/hoping for incoming messages. It will rule your day and compress your time. Instead, designate two 10-20 minute blocks per day to check your email. People can text, call, or ping you if it's truly urgent (wife giving birth, a death, an arrest, an accident).

Move.

Everyone knows that the faster you move through space, the slower time unfolds. We see this in sci-fi movies about astral explorers aging more slowly on interstellar journeys, but there's no reason it doesn't also work on a local, micro level, even if just barely and mostly imperceptibly. Try it out if you don't believe me.

Spend one day on the couch mainlining the latest Netflix show. Watch an entire season of something you haven't seen before, so it retains novelty. Get up only to use the bathroom.

Spend one day exploring the city on foot. Walk briskly, bike, whatever you want. Just physically move through space without stopping.

Which one took longer? Which was a fuller, richer day? They both introduced novelty, so that shouldn't be confounding the results. The only difference was physical movement.

Comment: There are many other reasons why movement and exercise are beneficial versus being inactive for hours on end, particularly when combined with watching TV:

- Three hours of sitting can damage your blood vessels

- Sitting for too long can do harm to your body

- The synergistic effects of exercise cannot be 'bought'

- Watching TV is bad for your health

Disconnect.

Scientists think our relationship to technology has sped up our perception of time. In a series of human experiments (results awaiting peer-review), researchers discovered that people who are constantly connected to technology perceive time to flow faster. What was actually 50 minutes felt like an hour to the tech addicts, who were more anxious and stressed about time running out than the folks who used technology less.

Plan trips.

Doesn't this conflict with "Be spontaneous"? No. Bear with me. If you've got a big trip coming up, rather than wait til the last minute to book the AirBNB and decide where you'll actually be going, give it some thought. This doesn't mean you have to plan everything down to the last detail. You don't have to decide now where to have breakfast on the sixth day. Planning a bit, even if it's just a skeleton plan, gives you something to look forward to. It extends and enriches the trip beyond the trip itself. You'll spend the four or five months eagerly anticipating the trip. You'll spend the two to three weeks actually on the trip. And you'll have the rest of your life to savor the memories. Throwing together a rough itinerary several months out, one that leaves plenty of room for improvisation, can really increase the density of your experience and thus slow your perception of time.

Go into nature.

We're slaves to the clock. In the wilderness, there are none. Rather than seconds and minutes, out there time is measured in seasons, sunrises and sunsets, temperature changes. It's a much grander thing embedded in the landscape itself. The linear tick of a digital display cannot hope to contain it.

Comment: Spending time in natural settings can benefit your health and emotional well-being in numerous ways:

If our perception of time is sped up by the mundane then why does time "fly when you're having fun?"