These findings raise the possibility that such contact is a major health determinant, and that greening may constitute a powerful, inexpensive public health intervention. It is also possible, however, that the consistent correlations between greener surroundings and better health reflect self-selection - healthy people moving to or staying in greener surroundings. Examining the potential pathways by which nature might promote health seems paramount — both to assess the credibility of a cause-and-effect link and to suggest possible nature-based health interventions. Toward that end, this article offers: (1) a compilation of plausible pathways between nature and health; (2) criteria for identifying a possible central pathway; and (3) one promising candidate for a central pathway.

How Nature Might Promote Health: Plausible Pathways

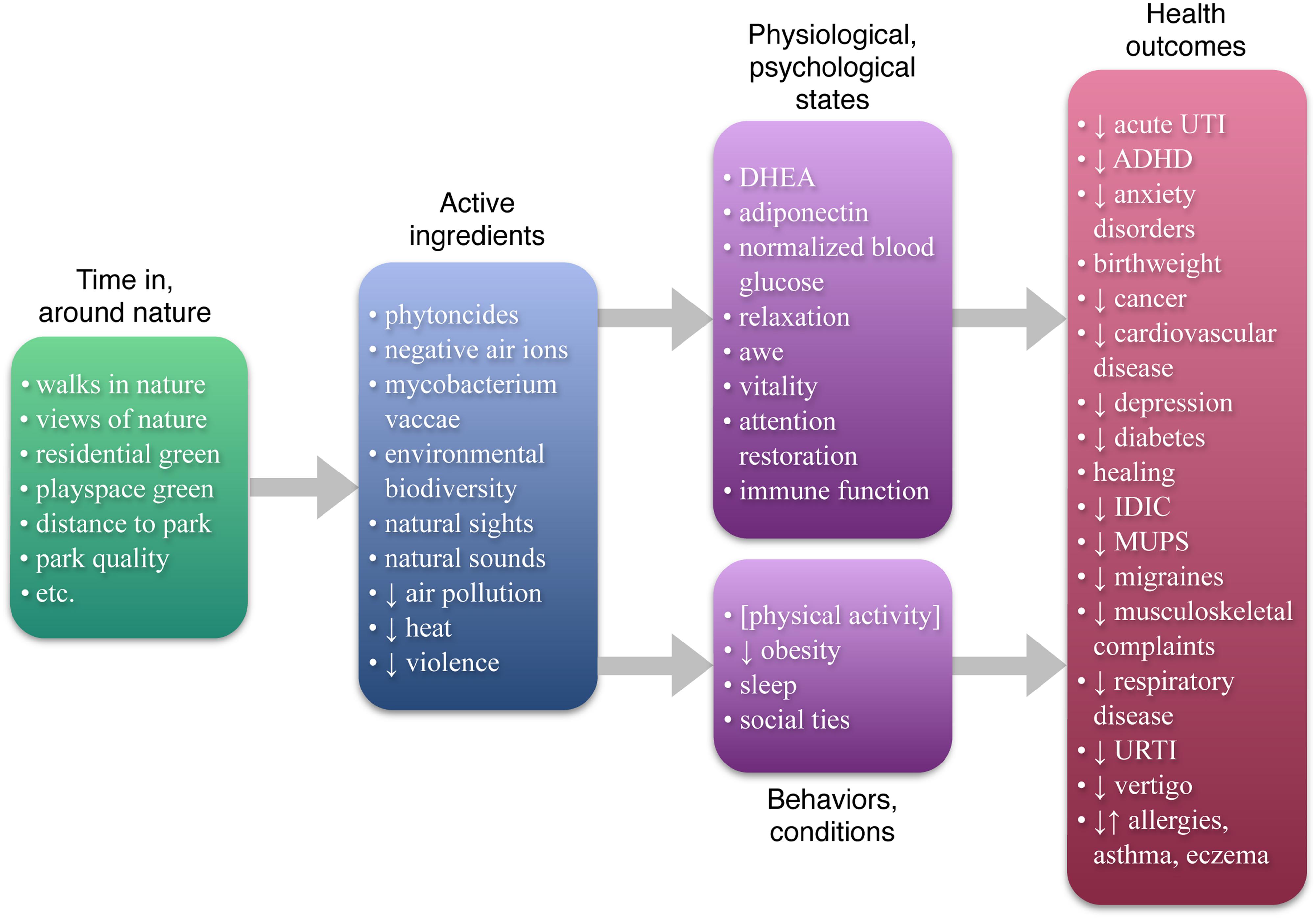

How might contact with nature promote health? To date, reviews and studies addressing multiple possible mechanisms (Groenewegen et al., 2006, 2012; Sugiyama et al., 2008; de Vries et al., 2013; Hartig et al., 2014) have focused on four - air quality, physical activity, stress, and social integration. But the burgeoning literature on nature benefits has revealed an abundance of possible mechanisms: as Figure 1 shows, this review identifies 21 plausible causal pathways from nature to health. Each has been empirically tied to contact with nature while accounting for other factors, and is empirically or theoretically tied to specific health outcomes (for details on the scope of this review, see Table 1 in the Supplementary Materials). The 21 pathways identified here include environmental factors, physiological and psychological states, and behaviors or conditions, and are summarized below (for more details on each of these pathways, see Table 2 in the Supplementary Materials).

Some of the plausible pathways from contact with nature to improved health stem from specific environmental conditions. Natural environments contain chemical and biological agents with known health implications. Many plants give off phytoncides — antimicrobial volatile organic compounds — which reduce blood pressure, alter autonomic activity, and boost immune functioning, among other effects (Komori et al., 1995; Dayawansa et al., 2003; Li et al., 2006, 2009). The air in forested and mountainous areas, and near moving water, contains high concentrations of negative air ions (Li et al., 2010), which reduce depression (Terman et al., 1998; Goel et al., 2005), among other effects (Table 2 in the Supplementary Materials). These environments also contain mycobacterium vaccae, a microorganism that appears to boost immune functioning (see Lowry et al., 2007 for review). Similarly, environmental biodiversity has been proposed to play a key role in immune function via its effects on the microorganisms living on skin and in the gut, although the evidence for this is mixed (Table 2 in the Supplementary Materials).

The sights and sounds of nature also have important physiological impacts. Window views and images of nature reduce sympathetic nervous activity and increase parasympathetic activity (e.g., Gladwell et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2013), restore attention (e.g., Berto, 2005), and promote healing from surgery (Ulrich, 1984). Sounds of nature played over headphones increase parasympathetic activation (Alvarsson et al., 2010). These sympathetic and parasympathetic effects drive the immune system's behavior (for review, see Kenney and Ganta, 2014), with long-term health consequences.

In built environments, trees and landscaping may promote health not only by contributing positive factors like phytoncides but also by reducing negative factors. Air pollution is associated with myocardial inflammation and respiratory conditions (Villarreal-Calderon et al., 2012). High temperatures can cause heat exhaustion, heat-related aggression and violence, and respiratory distress due to heat-related smog formation (Anderson, 2001; Akbari, 2002; Tawatsupa et al., 2012). And violence affects physical and mental health (e.g., Groves et al., 1993). Vegetation filters pollutants from the air (although see Table 2 in the Supplementary Materials for details), dampens the urban heat island (e.g., Souch and Souch, 1993), and appears to reduce violence (Table 2 in the Supplementary Materials for review).

Physiological and Psychological States

Some of the plausible pathways between contact with nature and health involve short-term physiological and psychological effects, which, if experienced regularly, could plausibly account for long-term health effects.

Blood tests before and after walks in different environments reveal that levels of health-protective factors increase after forest but not urban walks. Didehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) increases after a forest walk (Li et al., 2011); DHEA has cardio protective, anti-obesity, and anti-diabetic properties (Bjørnerem et al., 2004). Similarly, time in nature increases adiponectin (Li et al., 2011), which protects against atherosclerosis, among other things (Table 2 in the Supplementary Materials), and the immune system's anti-cancer (so-called "Natural Killer," or NK) cells and related factors (Table 2 in the Supplementary Materials). NK cells play important protective roles in cancer, viral infections, pregnancy, and other health outcomes (Orange and Ballas, 2006).

Further, walks in forested, but not urban areas, reduce the levels of health risk factors, specifically inflammatory cytokines (Mao et al., 2012), and elevated blood glucose (Ohtsuka et al., 1998). Inflammatory cytokines are released by the immune system in response to threat, and have been implicated in diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and depression (Table 2 in the Supplementary Materials). Chronically elevated blood glucose carries multiple health risks, including blindness, nerve damage, and kidney failure (Sheetz and King, 2002). The powerful effects of a walk in a forest on blood glucose are particularly striking (Table 2 in the Supplementary Materials for review).

Contact with nature has a host of other physiological effects related to relaxation or stress reduction (Table 2 in the Supplementary Materials). The experience of nature helps shift individuals toward a state of deep relaxation and parasympathetic activity, which improves sleep (El-Sheikh et al., 2013), boosts immune function in a number of ways (Kang et al., 2011), and counters the adverse effects of stress on energy metabolism, insulin secretion, and inflammatory pathways (Bhasin et al., 2013). Evidence suggests this pathway contributes substantially to the link between nature and health (Table 2 in the Supplementary Materials).

Three psychological effects of nature — experiences of awe (Shiota et al., 2007), enhanced vitality (Ryan et al., 2010), and attention restoration (Table 2 in the Supplementary Materials) — offer additional possible pathways between nature and health. Regular experiences of awe are tied to healthier, lower levels of inflammatory cytokines (Stellar et al., 2015); the ties between nature and awe, and awe and cytokines, respectively, may help explain the effects of forest walks on cytokines above. Similarly, feelings of vitality predict resistance to infection (Cohen et al., 2006) and lowered risk of mortality (Penninx et al., 2000). Attention restoration could theoretically reduce accidents caused by mental fatigue and, by bolstering impulse control, reduce risky health behaviors such as smoking, overeating, and drug or alcohol abuse (Wagner and Heatherton, 2010).

Read the remainder of the article here.

Comment: See also: