Scientists fear thawing permafrost beneath the ocean is causing methane to become free, forming underwater pingos - mounds of earth and ice - off the coast of the Yamal Peninsula in Siberia.

Similar structures are thought to be behind enormous craters that have appeared on the land on the peninsula as methane exploded out of the Earth.

The researchers warn the underwater pingos appear to be forming through the same process and are also at risk of causing huge blow outs under the ocean.

This could release huge amounts of methane - a potent greenhouse gas - into the atmosphere.

WHAT ARE PINGOS?

Pingos are lumps of ice covered by soil or seabed.

As permafrost melts, due to global warming, methane gas is released, and a build up can cause a leak or an explosion.

On-land pingos are typically formed when the water freezes into an ice core under soil, this is caused by the chilling temperatures of permafrost.

However, subsea pingos may be formed because of the thawing of subsea permafrost as it separates from methane-rich gas hydrates.

Gas hydrates are ice-like solids made of, among other things, methane and water.

They form and remain stable under a combination of low temperature and high pressure.

In permafrost the temperatures are very low and gas hydrates are stable even under the low pressure, such as on shallow Arctic seas.

Thawing of permafrost leads to temperature increases, which in turn leads to melting of gas hydrates, therefore, releasing the formerly trapped gas.

'Gas leakage from one of the ocean floor pingos offshore Siberia shows a specific chemical signature that indicates modern generation of methane.

'We suggest that the mound formed more recently, moving material physically upwards.'

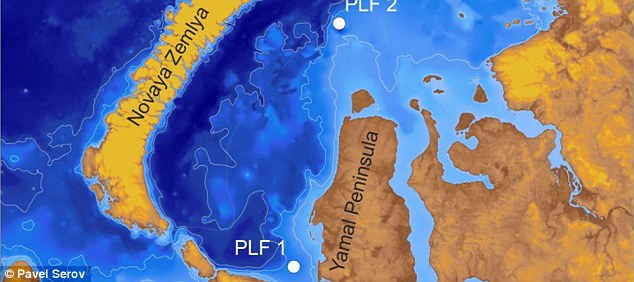

The pingos were discovered in the shallow South Kara Sea at a depth of around 131 feet (40m), just off the coast of the Yamal Peninsula.

The seabed there is formed of thick layers of permafrost that formed during the ice ages of the late Pleistocene.

As organic material trapped in the soil broke down this formed an icy substance known as gas hydrate.

When sea levels rose following the end of the last Ice Age 19,000 years ago, several million square miles of this frozen permafrost was flooded.

The researchers, whose work is published in the Journal of Geophysical Research, believe the underwater pingos may be forming because this relict permafrost is now thawing and the methane gas is being released.

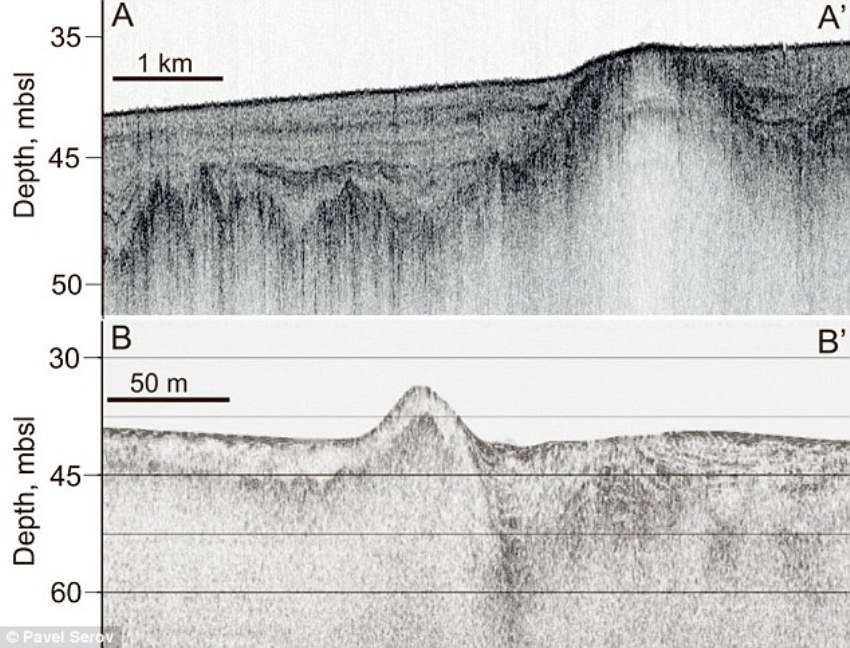

The mounds are roughly 230ft (70 metres) and a staggering 3,280ft (1,000 metres) in diameter.

They rise between 16ft (5 metres) and 30 ft (9 metres) above the surrounding sea floor.

The researchers warn that they could also pose a significant hazard to companies drilling for natural gas and petroleum in the arctic.

In 1995 the Russian vessel Bavenit got into trouble while undertaking 'geotechnological drilling' after drilling into one of these mounds and triggering a sudden methane release west of Vaygach Island in the Pechora Sea.

Dr Serov said: 'Pingos are intensively discussed in the scientific community especially in the context of global climate warming scenarios. They may be the step before the methane blows out.

'We don't know if the methane expelled from the subsea pingos reaches the atmosphere, but it is crucial that we observe and understand these processes better, especially in shallow areas, where the distance between the ocean floor and the atmosphere is short.'

Comment: The 'warming' that is taking place is likely due to increased volcanic activity, especially under the Arctic Ocean, where methane clathrate deposits are being ruptured in enormous quantities these days, releasing methane gas into the atmosphere. Recently an active underwater volcano was discovered spewing methane gas in southern Alaska.

Sinkholes and fissures of all descriptions appearing all over the world in recent years, as the planet is literally 'opening up'. A few recent incidents include: