These people are tone-deaf, a disorder known as congenital amusia. People who are really tone-deaf aren't just bad at karaoke: They can't pick out differences in pitch, the quality of music we're referring to when we say something is "low" or "high."

Say you're listening to your neighbor practice the piano, for example. In general, you could probably say whether the note you just heard was higher or lower than the one you heard before that.

People who are tone-deaf lack that ability. They still hear a difference, but they don't process it the same way as someone who isn't tone-deaf.

A world that sounds completely different

We talked to Marion Cousineau, a researcher at the International Laboratory for Brain, Music and Sound Research at the University of Montreal who spent years working with people with amusia (or "amusics") in the lab to get a sense of what the world sounds like to them.

Each person she's talked to, Cousineau said, describes their amusia a little bit differently.

While some people hear clanging pots and pans, for example, others might hear sounds they find beautiful. In the lab, they find out if participants have amusia using a version of this test, which you can try online right now.

"We had a journalist once who came to the lab to do a piece on it once. He was crazy about music and was constantly going to shows and concerts. Then he took the test and found out he was amusic."

In other words, while some tone-deaf people might experience sound one way, others might experience it in a vastly different way.

Amusia runs in families

Exactly what causes tone-deafness is still somewhat mysterious, but researchers are finding some fascinating clues.From studying families, for example, scientists have been able to conclude that it's hereditary, meaning that if you have it, chances are higher that your children will too.

We also know that amusia is a type of agnosia, a word derived from Greek roots that together essentially mean "not knowing." Agnosias describe conditions characterized by an inability to connect your sensory input (what you're seeing, hearing, or feeling) with your previous knowledge about the thing that you're sensing.

Brains that don't know they're tone-deaf

A 2009 study got a bit closer to telling us what's happening in the brain of a tone-deaf person when she or he listens to music and hears noise instead. For that study, two groups of volunteers — one with amusia and one without — were hooked up to an EEG so researchers could take a look at some of the electrical activity in different areas of their brains.

They had both groups listen to a series of notes in which one was out of key.

Each time the out-of-tune notes were played, the researchers saw specific and similar activity across the brains of both groups. In other words, it appeared that amusic or not, everyone's brains were at least picking up on the mismatched sounds. But while both the non-amusics and amusics displayed similar brain activity in the first few milliseconds after hearing the sound, only the non-amusics displayed another smattering of activity a few hundred milliseconds later. This second burst of activity in people without tone deafness, the scientists reasoned, suggested that only the brains of people who were not tone deaf were communicating the harsh tune with a higher brain area, making them aware that they'd heard it.

In other words, the researchers suspect, while the brains of both groups had identified the harsh tune on some level, amusics were not aware that they'd done so.

"Their brains were picking it up," said Cousineau, "but they couldn't say there was a change."

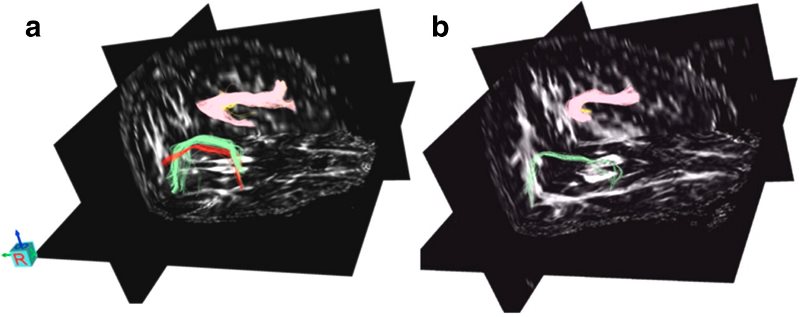

That idea has been bolstered by several other, more recent studies that suggest that amusics have weaker links between fronto-temporal brain areas, one of the regions we rely on to think critically and solve problems, and posterior auditory areas, important for processing sound.

What this growing body of work has shown is that in amusics, many aspects of the brain involved in experiencing music are working just as they should. But somewhere up the chain of command — between hearing a tune and processing it — something goes awry.

And this is responsible for the vastly different musical world that tone-deaf people experience.

"A lot of the people who'd come into the lab were told all their lives that they can't sing, that there's something wrong with them and that it's their fault," said Cousineau. "But it isn't their fault at all, and that's what we were able to share with them."

Reader Comments