Kennedy stated his demands in a letter to Levi Eshkol dated July 5, 1963, less than ten days after Eshkol became prime minister of Israel. The document is in the Israel State Archive, and is online at the National Security Archive, in a section titled Israel and the Bomb. Text below (thanks in part to the Jewish Virtual Library).

Avner Cohen, author of Israel and the Bomb, writes at the National Security Archive:

Not since President Eisenhower's message to [David] Ben Gurion, in the midst of the Suez crisis in November 1956, had an American president been so blunt with an Israeli prime minister. Kennedy told Eshkol that the American commitment and support of Israel 'could be seriously jeopardized' if Israel did not let the United States obtain 'reliable information' about Israel's efforts in the nuclear field. In the letter Kennedy presented specific demands on how the American inspection visits to Dimona should be executed. Since the United States had not been involved in the building of Dimona and no international law or agreement had been violated, Kennedy demands were indeed unprecedented. They amounted, in effect, to American ultimatum.What's the larger context?

In The Samson Option: Israel's Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy (1991), Seymour Hersh reports that Kennedy was dead-set against Israel getting the bomb and frequently pressured David Ben-Gurion, Eshkol's predecessor, to agree to inspections at Dimona. Kennedy even sold out his concerns about Palestinian refugees' return in order to gain concessions on Dimona - much to the consternation of the State Department. Hersh says that the Israelis misled American inspectors at the site, which had gone "critical" in 1962 with the help of the French. And some members of Congress undercut Kennedy's policy in private communications with the Israelis.

Lyndon Johnson succeeded Kennedy as president on November 22, 1963, of course. He was also opposed to Israel getting the bomb, Hersh says. "A nuclear Israel was unacceptable." But Johnson was in the end more accommodating: "By the middle 1960s, the game was fixed: President Johnson and his advisers would pretend that the American inspections amounted to proof that Israel was not building the bomb, leaving unblemished America's newly reaffirmed support for nuclear nonproliferation."

"Unlike Kennedy, Johnson was not eager for a confrontation," Michael Karpin writes in The Bomb in the Basement. "He preferred compromise." Israel achieved nuclear capability in 1966, he says.

Comment: Obviously. He saw firsthand what would happen to him if he didn't 'compromise'. And he profited mightily from Kennedy's assassination, which he probably had a hand in.

Both Karpin and Hersh attribute Johnson's winking acceptance of Israel into the nuclear club to his sensitivity to the Jewish experience in the Holocaust and the effect of what both men call "the Jewish lobby." Hersh mentions Johnson's dependence on financial contributions from Abraham Feinberg.

Here is that Kennedy letter:

"Dear Mr. Prime Minister:

"It gives me great personal pleasure to extend congratulations as you assume your responsibilities as Prime Minister of Israel. You have our friendship and best wishes in your new tasks. It is on one of these that I am writing you at this time.

"You are aware, I am sure, of the exchanges which I had with Prime Minister Ben-Gurion concerning American visits to Israel's nuclear facility at Dimona. Most recently, the Prime Minister wrote to me on May 27. His words reflected a most intense personal consideration of a problem that I know is not easy for your Government, as it is not for mine. We welcomed the former Prime Minister's strong reaffirmation that Dimona will be devoted exclusively to peaceful purposes and the reaffirmation also of Israel's willingness to permit periodic visits to Dimona.

"I regret having to add to your burdens so soon after your assumption of office, but I feel the crucial importance of this problem necessitates my taking up with you at this early date certain further considerations, arising out of Mr. Ben-Gurion's May 27 letter, as to the nature and scheduling of such visits.

"I am sure you will agree that these visits should be as nearly as possible in accord with international standards, thereby resolving all doubts as to the peaceful intent of the Dimona project. As I wrote to Mr. Ben-Gurion, this government's commitment to and support of Israel could be seriously jeopardized if it should be thought that we were unable to obtain reliable information on a subject as vital to peace as the question of Israel's effort in the nuclear field.

"Therefore, I asked our scientists to review the alternative schedules of visits we and you had proposed. If Israel's purposes are to be clear beyond reasonable doubt, I believe that the schedule which would best serve our common purposes would be a visit early this summer, another visit in June 1964, and thereafter at intervals of six months. I am sure that such a schedule should not cause you any more difficulty than that which Mr. Ben-Gurion proposed in his May 27 letter. It would be essential, and I understand that Mr. Ben-Gurion's letter was in accord with this, that our scientists have access to all areas of the Dimona site and to any related part of the complex, such as fuel fabrication facilities or plutonium separation plant, and that sufficient time be allotted for a thorough examination.

"Knowing that you fully appreciate the truly vital significance of this matter to the future well-being of Israel, to the United States, and internationally, I am sure our carefully considered request will have your most sympathetic attention.

"Sincerely,

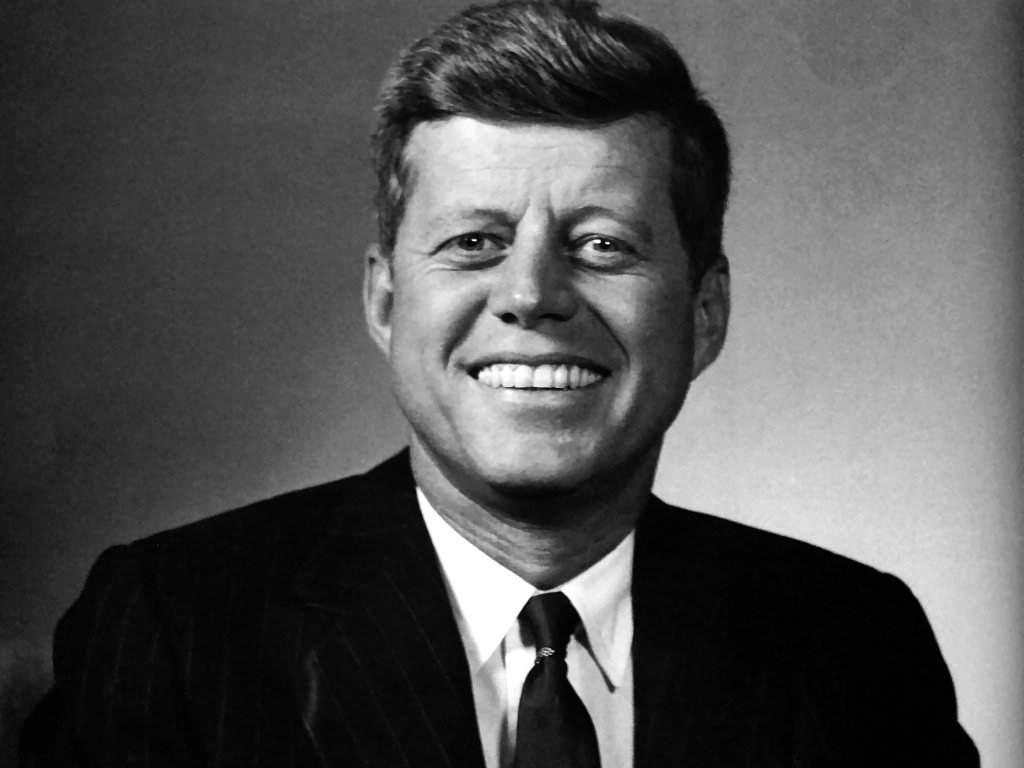

"John F. Kennedy"

to the gold standard which would have destroyed the Jewish-owned private bank known as the Federal Reserve. You just don't mess with the Rothschilds and their money collection industry. The IRS is the collection arm of the FED and the FED is the collection arm of the Rothschilds.