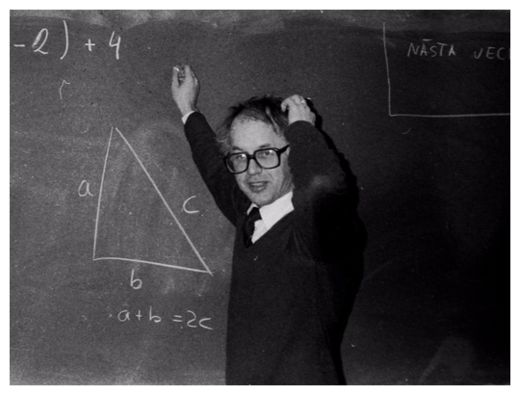

© Business InsiderSelf-proclaimed experts may be more susceptible to the illusion of knowledge.

Here's a trick you can try at the next party you attend: Come up with a completely bogus money term and then ask your financial expert friend to explain it to you.

Chances are he'll make a fool of himself when he assumes it's a real concept and claims to know all about it.

That's according to new research, which suggests that self-proclaimed experts are more susceptible to the "illusion of knowledge." In other words, people who believe they know a lot about a particular topic are more likely to claim they know about fake concepts related to that topic.This phenomenon, called "overclaiming," could easily undermine you and work, making you look like an arrogant idiot or leading you to offer bad advice to others seeking your expertise.

The

study, led by Stav Atir, a graduate student at Cornell University,

tested this phenomenon among self-proclaimed experts in fields like personal finance, biology, and literature.

In one experiment, 100 participants were asked to rate their general knowledge of personal finance as well as their knowledge of 15 financial terms. Most of the terms on the list were real (e.g., "Roth IRA" and "inflation"), but participants also saw three made-up terms ("pre-rated stocks," "fixed-rate deduction," and "annualized credit").

As it turns out, those who said they knew a lot about finance were most likely to claim familiarity with the made-up terms.

In another experiment, participants were warned that some of the terms on the list would be made up. Still, those who claimed to be experts in specific fields were more likely to say they knew the made-up terms. For example, self-perceived experts in biology said they knew fake terms like "meta-toxins" and "bio-sexual."

To ensure that people's self-perceived expertise was the reason why they overestimated their knowledge, the researchers made some participants feel like geography whizzes and then tested their knowledge on the topic. Some people took an easy quiz on US cities; others took a difficult quiz; and some people didn't take any quiz.

As predicted, participants who completed the easy quiz (presumably feeling like geography experts) were more likely to say they knew made-up cities like Monroe, Montana, and Cashmere, Oregon.

"Our work suggests that the seemingly straightforward task of judging one's knowledge may not be so simple," the authors write.The authors also highlight the potential adverse effects of thinking you know more than you do. "Self-perceived experts may give bad counsel when they should give none," they write. For example, a self-perceived financial expert may give inappropriate advice to a friend making an important money decision — instead of taking the time to really learn about the topic.

Perhaps a wiser choice than pretending to be familiar with an unfamiliar topic is simply to

admit you don't know about it. It may even make you look smart — which you certainly won't when it turns out you just lectured your friends on a topic that doesn't exist.

The relationship between 'the expert' and the believer in 'expertise', is a highly incestuous one. They are of a 'kind' (made of the same stuff) and each is fully dependent on the other to maintain the status quo, ie., the belief system.

The current belief system is of course, the cult of technology.

Both experts and expert followers and believers of the cult of technology are getting stupider and stupider.

Only because the Universe itself is so highly intelligent can such stupidity exist and actually increase and 'flourish', as it has.

It is rather a paradox.

Think about it.

ned, out....