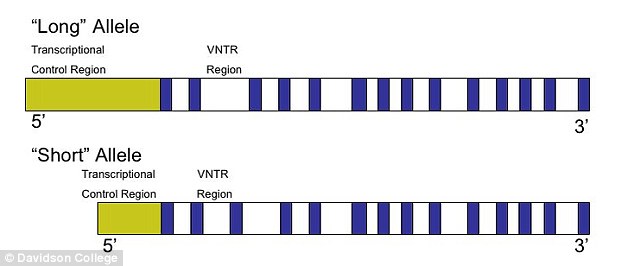

- Study looked at short and long alleles, or variants, of gene 5-HTTLPR

- This is involved in the regulation of a chemical known as serotonin

- Research found the short allele amplifies emotional reactions during both good and bad environments

People with a specific gene variant, which affects the way the brain chemical serotonin works, smiled and laughed more while watching cartoons or amusing films. And data from the experiments indicated that people with the short variations of the gene showed greater positive emotional expressions in general.

In the study by Northwestern University in Illinois, the researchers looked at short and long alleles - or variants - of the gene 5-HTTLPR. This is involved in the regulation of serotonin, a neurotransmitter involved in depression and anxiety.

While previous research has found that those with the short version were more sensitive to negative emotions than those with the long version, this study found they were more responsive to the emotional highs of life as well. 'Having the short allele is not bad or risky,' said researcher Dr Claudia Haase. 'Instead, the short allele amplifies emotional reactions to both good and bad environments.

'People with short alleles may flourish in a positive environment and suffer in a negative one, while people with long alleles are less sensitive to environmental conditions.'

For the study, published in the journal Emotion, participants were shown newspaper-style cartoons or a 'subtly amusing' clip from the film Strangers In Paradise. The scientists videotaped the volunteers' faces and then researchers who were trained in distinguishing real laughter and smiles coded their responses. Because people sometimes smile or laugh - even if they don't find something funny - simply to be polite or to hide negative feelings, the researchers focused on subtle signals.

'The important clues lie in the muscle around the eyes that produce the so-called crow's feet,' said study co-author Ursula Beermann, of the University of Geneva. 'Those can only be seen in real smiles and laughs.'

The researchers also collected saliva samples from the volunteers to analyse the 5-HTTLPR gene.

The data from the experiments indicated that people with the short allele of the gene showed greater positive emotional expressions. Specifically, people with the short allele displayed greater genuine smiling and laughing than people with the long allele. 'This study provides a dollop of support for the idea that positive emotions are under the same tent as negative ones, when it comes to the short allele,' said another of the researchers, Robert Levenson from the University of California-Berkeley.

'It may be that across the whole palate of human emotions, these genes turn up the gain of the amplifier. 'It sheds new light on an important piece of the genetic puzzle.'

Then the usual question is nature or environment? Born that way or made that way? Or a little of each, or a lot?