Americans had to be convinced their breath was rotten and theirs armpits stank. It did not happen by accident. "Advertising and toilet soap grew up together," says Katherine Ashenburg, author of The Dirt on Clean. As advertising exploded in the early 20th century, so did our obsession with personal hygiene.

Even our very notion of "soap" changed. Until the mid-19th century, "soap" meant laundry soap, the caustic stuff used for scrubbing soiled linens and clothes. A kinder, gentler alternative was invented for cleaning the body, and it had to be called "toilet soap" to distinguish from the unrefined stuff. Today, "toilet soap" is a superfluous designation. Toilet soap is simply soap.

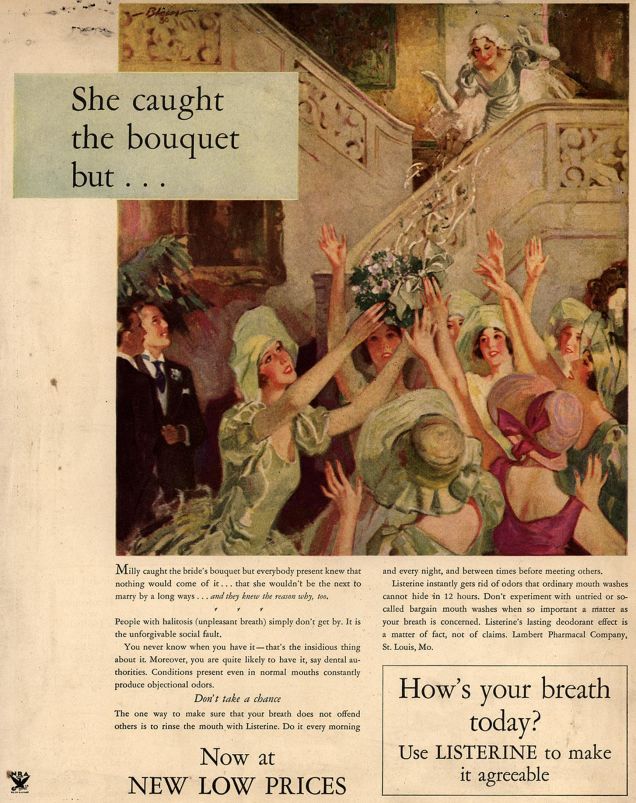

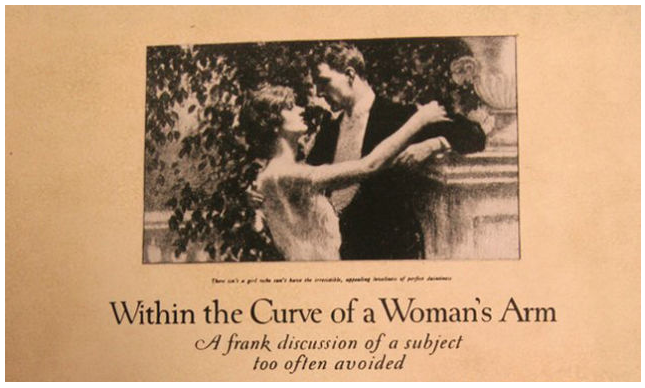

Advertisers did not invent a notion of cleanliness out of a vacuum, but they did cannily tap into anxieties wrought by social upheavals in the early 20th century. As people moved from farm to factory to office, working spaces became where they spent all day with strangers in closer and closer quarters. Men and women began to work together. Women, especially, were a target of ads playing on the theme, "Often a bridesmaid, never a bride."

And to be sure, advances in science and technology played a role, too. Plumbing made the weekly ritual of a Saturday night, pre-Sabbath bath easy to repeat every night of the week. Public health campaigns born out of a better understanding of germ theory trumpeted cleanliness.

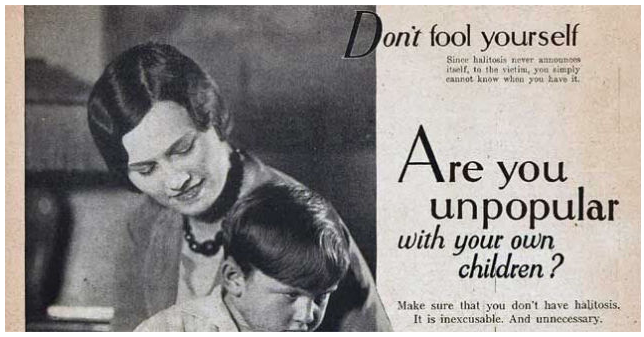

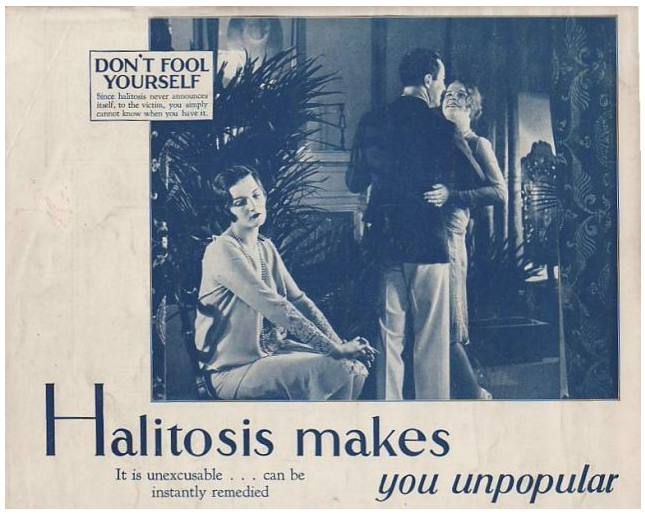

Amidst all this, a new affliction called halitosis descended upon American. You know about it thanks to Listerine, the orchestrator of what maybe be one of the most successful advertising campaigns in history.

How Listerine Made Americans Terrified of Bad Breath

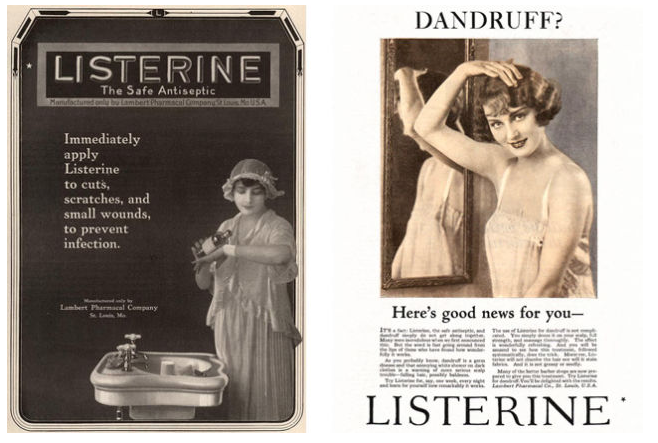

There's a reason why Listerine is so nasty—it wasn't originally meant to go in your mouth. When Joseph Lawrence invented the alcohol-based liquid in 1879, he created it as disinfectant for surgery. And for the first several decades of Listerine's existence, it was only available to doctors.

Halitosis lent Listerine the authoritative air for a fantastically successful advertising campaign, creating a market for the novel product of mouthwash. In an early version of A/B testing, coupons were sent out accompanying old and new-style Listerine ads. The halitosis ads did four times as well. Sales climbed 33 percent in just the first month.I asked him if Listerine was good for bad breath. He excused himself for a moment and came back with a big book of newspaper clippings. He sat in a chair and I stood looking over his shoulder. He thumbed through the immense book.

"Here it is, Gerard. It says in this clipping from the British Lancet that in cases of halitosis . . ." I interrupted, "What is halitosis?" "Oh," he said, "that is the medical term for bad breath."

[The chemist] never knew what had hit him. I bustled the poor old fellow out of the room. "There," I said," is something to hang our hat on."

From then on, Listerine took out a parade of advertisements insinuating that bad breath was pervasive, but people were simply too polite to tell you. Bad breath I mean halitosis was secretly holding you back, and only Listerine could fix it.

Lambert would become the third largest advertiser in major American magazines, according to Vincent Vinikas in Soft Soap, Hard Sell. The company created the demand for a product Americans did not know they wanted, let alone needed. And it's not just bad breath Americans came to fear.

The Ad Man Who Launched His Career With Antiperspirant

James Webb Young, one of the legendary ad men of the 20th century, was still a young copywriter when he got the Odorono account. Odorono was, well, not great. As Sarah Everts describes in a fascinating piece in Smithsonian Magazine, the antiperspirant's acid solution had a nasty habit of eating through clothes, including one woman's wedding dress.

A bigger problem, though, was a pervasive belief that blocking sweat was bad for health. To counter that, Young's first advertisements emphasized Odorono's origins as a formula developed by a doctor. But he ran into an even bigger problem, which is that a survey revealed two-thirds of women didn't feel like they needed to use antiperspirant. And here, Young found his true target for selling Odorono: embarrassment.

The 1919 ad in the Ladies Home Journal (above) hit a nerve. Two hundred angry subscribers supposedly canceled their subscriptions because they were so insulted by the ad. But it also worked. Sales for Odorono doubled in the next year. Competitors like Mum (below) jumped on the "whisper copy" train, insinuating what people were supposedly too polite to say directly.

The Cleanliness Institute

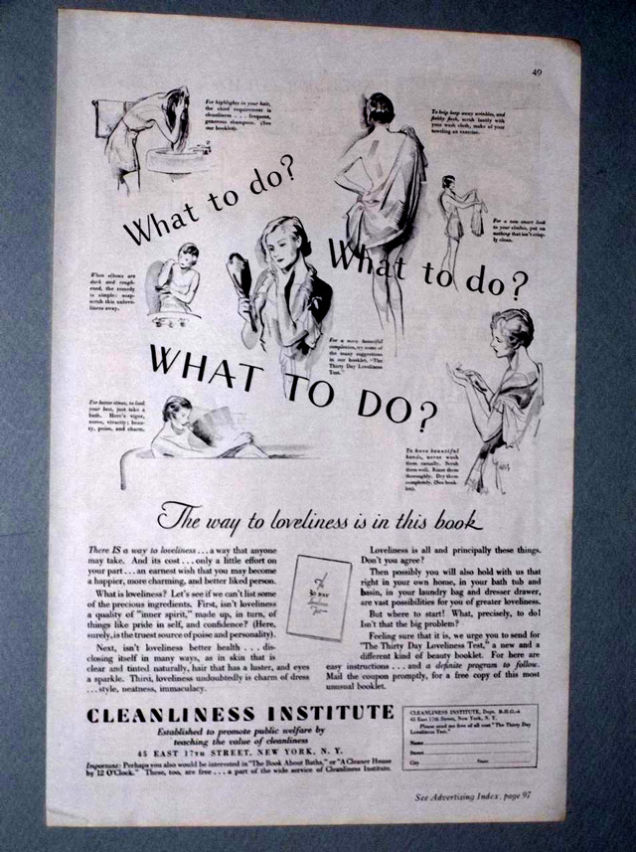

Early on, the soapmakers also realized that advertising could only do so much to differentiate brands—what they really needed to do was band together to convince Americans that cleanliness was paramount. Thus, the Association of American Soap and Glycerine Producers established the friendlier sounding Cleanliness Institute in 1927. The institute could promote keeping clean and, by extension, soap consumption.

The industry cannily made school children its primary target. "No approach could better meet the industry's ends than inculcating every youth in American to a tale of soap-and-water. Once habituated to regular and frequent consumption, the children could guarantee a market for years to come," writes Vincent Vinikas in an excellent chapter on the institute from his book Soft Soap, Hard Sell.

As one of its first major activities, the institute conducted a study of the hygiene habits of students in 145 schools. They found, by their own standards much room for improvement. Only 57 percent of the schools had soap. "The object should be not merely to make children clean but to make them love to be clean," read an institute report.

So the institute set about correcting the course with a flurry of storybooks, teacher's guides, and and posters. Teachers were to write letters to parents about the cleanliness. In one case, the institute reported on a school where students were given "wash tickets" after washing their hands. Only by presenting these tickets could they even enter the school cafeteria.

The methods may read as heavy-handed today, but the habits promoted by the Cleanliness Institute will be utterly familiar. "The trade association wanted Americans to to wash quite unwittingly after toilet, to wash without thought before eating, to jump into the tub as automatically as one might awake each new day," writes Vinikas.

That vision is not far from today's reality. If anything, the grooming products deemed essential for proper hygiene have only proliferated. Even a quick stroll through the drugstore—past what seems like infinite varieties of shampoo and deodorant and whatever new product just rolled out of the factories—can tell you that.

One of the big disagreements I have as a humble and small dairy farmer, with the dairy industry and in particular (in my case) the organic segment, is the total wastage of water on a typical dairy farm and the vast amount of other product and packaging one is supposed to add to the water (and to the milk, and the cows) and that one (as a dairyman) must purchase and rely on to produce wholesome, 'good' and 'safe', 'healthy' milk.....

My own reasoning goes along the lines that milk produced in the '60's (for example) under far less scrupulous and demanding (wasting) routines and regulations with much less bureaucratic interference and control and technological 'efficiency' was far superior to milk produced now. As it also just so happens, so was everything else edible then and before GMO and glyphosate basically superior to now.

And there were many more farms! And a good deal less total chronic and diseased, damaged beyond repair dipshits, as I recall.....

But I am, as noted by myself, here at Sott previously, am a madman, a Luddite and a backassward bum who can't advance and won't compete properly in modern theater/showtime and organize my energy toward the highly tenuous and precipitous market of product and sales and aggressive advertising (propaganda, mind control) with the other actors and film stars, agents and directors and idol worshippers.

I can't act and I won't lie. What a bum. What a fucking bum.

ned, out