In mid-July, reindeer herders stumbled across a crater that was approximately 260 feet (80 meters) wide, on the Yamal Peninsula, whose name means "end of the world," The Siberian Times reported. Since then, two new chasms - a 50-foot (15 m) crater in the Taz district and a 200- to 330-foot (60 to 100 m) crater in the Taymyr Peninsula - have also been reported.

Neither aliens nor meteorites caused the strange cavities, as some had speculated, but the true explanation could be exciting nonetheless. Russian scientists have launched an investigation to find out more.

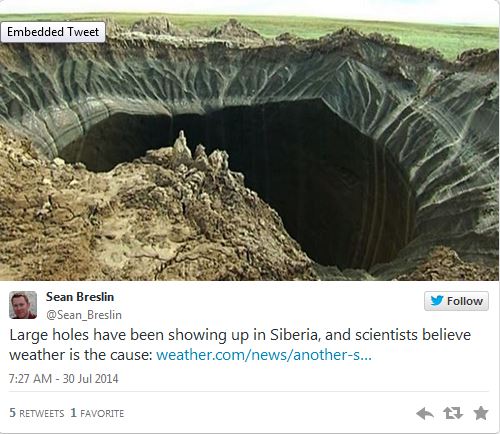

Helicopter video footage of the first hole shows it is surrounded by a mound of loose dirt that appears to have been thrown out of the hole.

"My personal opinion is it's some type of sinkhole," said Vladimir Romanovsky, a geophysicist who studies permafrost at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Sinkholes are pits in the ground formed when water fails to drain away.

The water likely came from melting permafrost or ice, said Romanovsky, who has spoken with the Russian scientists investigating the site. But whereas most sinkholes suck collapsed material inside, "this one actually erupted outside," he told Live Science. "It's not even in the [scientific] literature. It's pretty new what we're dealing with," he added.

Early on, polar scientist Chris Fogwill of the University of New South Wales, in Australia, suggested the first hole was created by the collapse of a pingo, a large, earth-covered mound of ice that usually forms in Arctic and subarctic regions.

Kenji Yoshikawa, an environmental scientist also at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, said he also thinks that a drained, collapsed pingo pond is the most likely explanation for the Yamal Peninsula pit. In Alaska, similar pingos exist in the Northern Seward Peninsula and near the city of Nuiqsut.

But Romanovsky said the hole doesn't look like a typical collapsed pingo; such features usually form from larger mounds that slowly cave in over a period of decades, with all the material falling inside.

From the photo of the Yamal crater, "it's obvious that some material was ejected from the hole," Romanovsky said. His Russian colleagues who visited the site told him the dirt was piled more than 3 feet (1 m) high around the hole's edges.

The crater's formation probably began in a similar way to that of a sinkhole, where water (in this case, melted ice or permafrost) collects in an underground cavity, Romanovsky said. But instead of the roof of the cavity collapsing, something different occurred. Pressure built up, possibly from natural gas (methane), eventually spewing out a slurry of dirt as the ground sunk away. Anna Kurchatova, a scientist at the Sub-Arctic Scientific Research Center in Russia, made a similar observation to The Siberian Times.

The photo of the crater rim shows some vegetation that does not appear freshly grown, which suggests the hole may be several years old, Yoshikawa said. Romanovsky said it might be more recent, but investigators will need to look at archived high-resolution satellite images to pin down exactly when the crater appeared.

And many other questions remain: If a sinkhole erupted material, why is the hole's border so round and even? Would there be enough gas to fuel such an eruption, and where did such gas come from?

This part of Siberia contains deep gas fields, and it also contains a lot of small lakes, which formed between 4,000 and 10,000 years ago when the climate was warmer, Romanovsky said. Perhaps these odd holes developed in the same way that sinkholes did, but later expanded.

Domes of natural gas also exist in the United States, located east of the Sagavanirktok River in Alaska's North Slope Borough.

The development of permafrost sinkholes could be one indication of global warming, Romanovsky. "If so, we will probably see this happen more often now."

Underground Bases and Tunnels - What is the government trying to hide? by Richard Sauder, Ph.D talks about large underground drilling machines that make symmetrical holes with smooth sides that definitely resemble the ones in these pictures and video. Tunnel Boring Machines or "TBM's" (made by Robbins Co.) and Vertical Shaft Drilling Machines are massive. The ones depicted are not 80M wide, but who knows. Food for thought.