The answer is yes, it probably will. But it's not worth losing sleep over, experts say. (See "Q&A: Ebola Spreads in Africa - And Likely Will Spread Beyond.")

The virus is one of the deadliest ever seen, killing up to 90 percent of its victims. And the death isn't pretty. About half of patients exhibit the gruesome bleeding symptoms typical of any hemorrhagic fever - seared into the American consciousness by the 1995 movie Outbreak. But it can also resemble other tropical diseases, like dengue with its high fever, so Ebola is sometimes missed in its early stages.

That may be why a feverish man was able to board a plane last week from Liberia to the Nigerian city of Lagos, Africa's most populous city. He fell ill on the flight and was taken directly to a hospital, where he was isolated and later died.

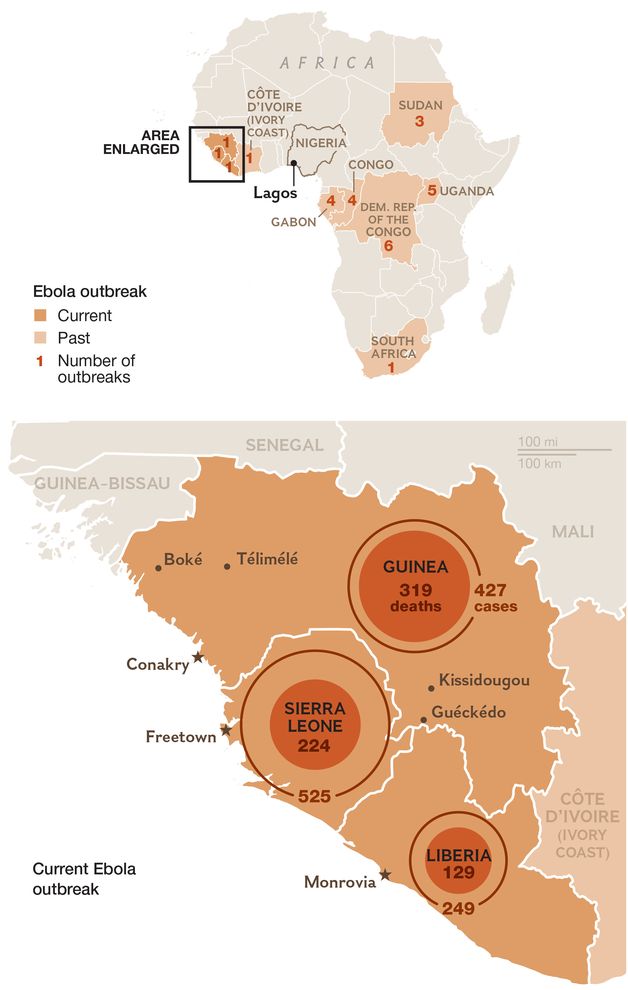

Ebola outbreaks grow

The deadly Ebola virus has been devastating parts of Africa since the first outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1976. In the latest outbreak, the World Health Organization has reported 1,201 cases and 672 deaths since March of this year, in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. Last Friday, a Liberian man died after his plane landed in Lagos, Nigeria, one of the world's largest cities.

Maggie Smith, NG Staff; Joey Fening

Air Passengers Monitored

Several West African nations are planning to set up monitoring at airports to try to identify people with fevers before they board planes. It makes more sense to put checkpoints in West African countries than to scan incoming passengers in the U.S., said Martin Cetron, the CDC's director for Global Migration and Quarantine.

There are few direct flights from West Africa to the U.S., so most feverish passengers entering American airports will have something far more routine and less risky than Ebola.

Ebola is contagious only when symptomatic, so someone unknowingly harboring the virus would not pass it on, Monroe said.

Even passengers showing symptoms are unlikely to pass the disease on to fellow travelers, he said.

Blood and stool carry the most virus - which is why those at highest risk for Ebola infection are family members who care for sick loved ones and health care workers who treat patients or accidentally stick themselves with infected needles.

Theoretically, there could be enough virus in sweat or saliva to pass on the virus through, say, an airplane armrest or a nearby sneeze, said Stephen Morse, an epidemiologist and virologist at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University in New York. But droplets would still need a way to get through the skin.

Health authorities are tracking the passengers and crew who flew from Liberia to Lagos, Monroe said, to ensure that they didn't catch Ebola from the sick man.

Airplane Risk Uncertain

The fact that experts are still unsure about the risks of airplane travel shows how unusual the current outbreak is. In the past, outbreaks have been focused in small rural villages, mostly in central Africa. Rural hunters generally bring the virus to their villages via infected monkeys killed for meat. But such villages are remote and can be easily quarantined, allowing the virus to burn itself out.

The current outbreak seems to have started in rural Guinea, but it was able to spread for some time before being reported to the World Health Organization.

These Guinean villages hadn't see the virus before, Morse said. A lack of familiarity with the disease, coupled with porous borders and burial rituals that exposed family members to the bodily fluids of the dead, led to much greater spread, he said.

"In places where they've seen Ebola outbreaks, both the local people and health authorities have some idea of what precautions to take," Morse said.

Lack of training and experience is compounded by the lack of basic infection-control equipment such as gloves. Using protective gear safely requires training and practice for health care workers, "especially how to take it off without accidentally contaminating equipment and themselves," Morse said. "It's partly a training matter and partly an equipment issue."

Bringing the outbreak under control in West Africa, Morse said, will require more equipment, better training in health care settings, and more outreach to rural healers and leaders to teach them how to reduce transmission.

More help from the outside world is essential, Morse said, adding that one of his colleagues in Sierra Leone is now treating patients "12 to 24 hours a day," according to an email he received Monday.

Because it's exhausting to keep up with all the necessary safety precautions, attention to detail can slip after such long hours of patient care, he said. Perhaps that's why 43 health care workers in Liberia, including two well-trained Americans, have come down with Ebola. The Americans are in stable condition, but are still symptomatic.

One of the Americans, a doctor, sent his family members home to the U.S. before becoming symptomatic with Ebola, Monroe said. His wife and children are on a fever watch for 21 days "out of an abundance of caution," to ensure that they don't come down with the virus, though Monroe said they are thought to be safe. Both the doctor and another American health care worker are still being treated.

Illness among health care workers has generated panic in the Liberian capital of Monrovia, where some hospitals have turned away accident victims because they are so fearful of anyone who is bleeding, said John Ly, medical director of Last Mile Health, a non-governmental agency that has been providing training, supplies, and other support in Liberia.

Raj Panjabi, Last Mile co-founder and CEO, said it is very clear that the epidemic can be brought under control in West Africa by rapidly identifying sick people, treating them, and preventing the disease from being spread.

But all that takes money, of course, and area governments and nonprofits don't have enough resources to tackle the problem on their own, Panjabi said.

Ebola in the U.S.?

So, could the Ebola virus come to the United States? Definitely. Would it spread widely? Unlikely.

"We do not anticipate this will spread in the U.S. if an infected person is hospitalized here," CDC Director Tom Frieden said in a statement Tuesday. "We are taking action now by alerting health care workers in the U.S. and reminding them how to isolate and test suspected patients while following strict infection-control procedures."

American hospitals are adequately supplied with infection-control equipment like gloves, gowns, and masks that will prevent the spread of the disease. American medical care workers - educated by the AIDS epidemic - know how to keep themselves safe while treating sick patients. And the American system of reporting illness would identify a sick patient very quickly, allowing the disease to be contained and controlled.

But it's still in America's interest to control the disease in West Africa, Panjabi said.

"If we respond well to this, we could both impact the epidemic - control it, stop it - but also do it in a way that strengthens the long-term primary care system," he said, which "could protect against future [epidemics]."

Comment: The author and CDC Director have a lot of faith in the American healthcare system. With the End of the $Dollar imminent, for those dependent on ObamaCare (allegedly the affordable Care Act) or unable to purchase any health care, this virus (or others with a cosmic source) may not be quite so easy to treat.