Those small specks turned out to be a type of pollution known as microplastics. Their presence in sea ice collected from the central Arctic Ocean showed that some of the vast quantities of garbage and pollution floating in the world's seas has traveled to the northernmost waters.

For Obbard, an assistant engineering professor who specializes in polar-ice studies, the appearance of microplastics in Arctic sea ice was an unpleasant surprise. "I was kind of shocked. I said, 'This shouldn't be here in such a remote place,'" she said.

Worse yet, that sea ice holding the small bits of trash is thinning and likely to shed them back into the water, where they can be ingested by fish, birds and mammals, said a study by Obbard and fellow scientists that was published online Tuesday in the scientific journal Earth's Future.

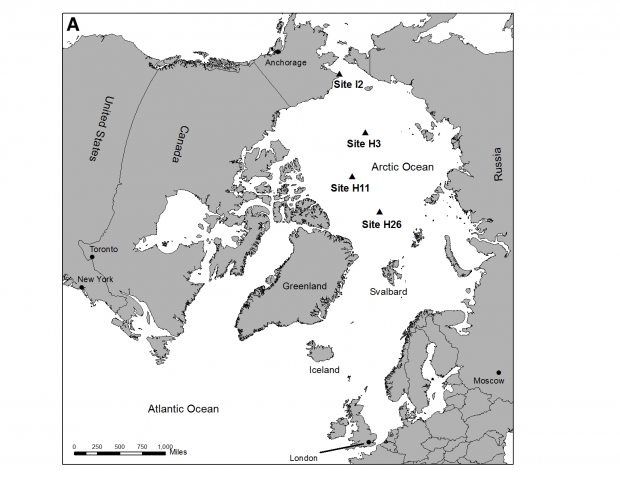

Extrapolating the findings from the examined cores and factoring in the ongoing transformation of thick multiyear ice to thinner, single-year ice, Obbard and her colleagues found that a staggering amount of plastic and synthetic trash could be released in coming years into Arctic waters. If other sea ice holds similar amounts of debris and current ice-melt trends continue, 2,040 trillion cubic meters of ice will melt in the next decade and more than 1 trillion pieces of these microplastics will be released from the melted ice into the water, the study authors calculated.The study results from analysis of ice cores, ranging from a meter to 3.5 meters, that were retrieved from the Arctic Ocean during two expeditions, one in 2005 that was funded by the Natonal Science Foundation in 2005 and one in 2010 that was funded by NASA. Obbard was examining the preserved ice to search for microorganisms known as diatoms when she encountered the objects, which were generally blue, green, red and black.

She melted the ice, filtered that water and sent the retrieved objects to Richard Thompson, a marine biologist at Britain's University of Plymouth, for analysis. Thompson is a co-author of the newly-published study.

The items found in the ice were generally under 2 millimeters in diameter and as small as .02 millimeters, according to the study.

The majority of the pieces, 54 percent, were rayon, a manmade material created out of cellulose and used to make clothing, cigarette butts, disposable diapers and other personal-hygiene products, among other consumer goods. The rest were pieces of various other types of polymers -- polyester, nylon, polypropylene, polystyrene, acrylic and polyethylene. Identifying the tiny pieces fell largely to Thompson, whose research has focused on marine debris, Obbard said.

There are several likely sources of the rayon and plastic bits found in the ice, Obbard said. One is the floating and relatively large pieces of trash in the oceans, which crumble into finer bits, she said. Other possible sources are the discharges of ingredients used to manufacture various consumer products and waste from faraway laundries, she said. "All that lint that comes off of clothing has to go somewhere," she said. And some of the pieces may be polymer beads, or remnants of those beads, that are contained in some cosmetic products.

Biologists worry about animals consuming pieces of ocean trash instead of the food they need.

A different study, co-authored by Thompson and published last year, found that similar microplastics had been ingested by fish in the English Channel. Of 504 fish examined, more than a third had the synthetic bits in their bodies, and the ratio of those pieces -- with 57.8 percent rayon -- was similar to what was discovered in the Arctic sea-ice cores.

More ominously, these microplastics can be "vectors" that carry persistent organic pollutants, Obbard said. A 2012 study of microplastics found on San Diego beaches found that the pieces carried some dangerous contaminants, including PCBs and the long-banned pesticide DDT.

Still unknown is where in the world the frozen-in-place bits of marine trash originated.

Obbard and her co-authors believe that at least some of the ice may have formed on the Alaska coast and was transported by the Beaufort Gyre. They hypothesize, based on patterns of currents and water flow, that the microplastics are coming to the Arctic from the Pacific Ocean.

Obbard said she would like to do more research, evaluating ice in several locations, to better understand how these tiny bits of plastic and synthetic waste are winding up in Arctic ice.

Comment: See also...