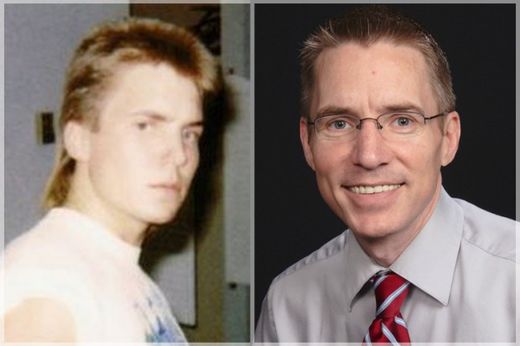

Jason Padgett

If you could see the world through my eyes, you would know how perfect it is, how much order runs through it, and how much structure is hidden in its tiniest parts. We're so often victims of things - I see the violence too, the disease, the poverty stretching far and wide - but the universe itself and everything we can touch and all that we are is made of the most beautiful geometric patterns imaginable. I know because they're right in front of me. Because of a traumatic brain injury, the result of a brutal physical attack, I've been able to see these patterns for over a decade. This change in my perception was really a change in my brain function, the result of the injury and the extraordinary and mostly positive way my brain healed. All of a sudden, the patterns were just . . .

there, and I realize now that my injury was a rare gift. I'm lucky to have survived, but for me, the real miracle - what really saved me - was being introduced to and almost overwhelmed by the mathematical grace of the universe.

There's a park in my town of Tacoma, Washington, that I like to walk through in the mornings before work. I see the trees that line its path as anyone would, the branches and the bark, but I see a geometrical blueprint laid on top of them too. I see triangular patterns emerging from the leaves, reminding me of the Pythagorean theorem, as if it's unfolding in the air, proving to me over and over again what the ancient Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras deduced thousands of years ago: the sum of the squares of the legs of a right triangle (a triangle in which one angle is a right angle, or 90 degrees) equals the square of its hypotenuse. I don't need a calculator to know that the simple formula most of us learned in school -

a2 + b2 = c2 - is true; I can see it instantly in the trees all around me. To me, a tree is more than its geometry, but geometry is also far more than most people realize. I think it's everything.

I remember reading that Galileo Galilei, the Italian astronomer, mathematician, and physicist (and one of my heroes), said that we cannot understand the universe until we have learned its language. Speaking of the universe, he said, "It is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometric figures, without which it is humanly impossible to understand a single word of it."

This rings true for me. I see this hidden language of the world before my eyes.

Doctors tell me that nothing in my brain was newly created or added when I was injured. Rather, innate but dormant skills were released. This theory comes from psychiatrist Darold Treffert, who is considered the world's leading authority on savants and acquired savants. He treated the late Kim Peek (the inspiration for the savant character in the movie

Rain Man), a megasavant who memorized twelve thousand books, including the Bible and the Book of Mormon, but who had so many physical challenges that he had to rely on his father for his most basic needs. When I met with Dr. Treffert in his hometown of Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, he told me that these innate skills are, in his words, "factory-installed software" or "genetic" memory. After interviewing me in his office and in his home, he declared that my acquired synesthesia and savant syndrome was self-evident, and he also suggested that all of us have extraordinary skills just beneath the surface, much as birds innately know how to fly in a V-formation and fish know how to swim in a school.

Why the brain suppresses these remarkable abilities is still a mystery, but sometimes, when the brain is diseased or damaged, it relents and unleashes the inner genius. This isn't just my story. It's the story of the potential secreted away in all of us.

Read more at Salon.com

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter