Britain has spent £600m on a stockpile of influenza drugs that are no better than paracetamol in relieving flu symptoms and are next to useless in preventing a pandemic, a major study has found.

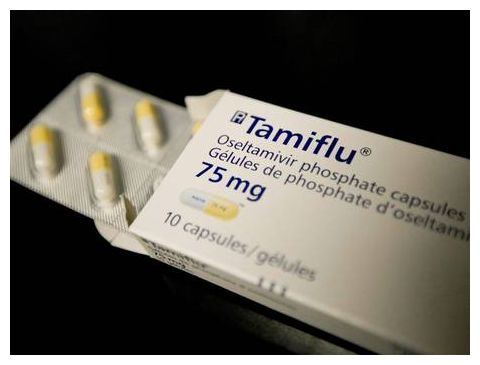

The companies behind the two main anti-influenza drugs Tamiflu and Relenza held back crucial information that would have shown just how ineffective their drugs were in clinical trials, according to the independent scientists who compiled the report.

Their investigation found little or no evidence to support the manufacturers' claims about the effectiveness of the two drugs and questioned the Government's rationale for building up an emergency stockpile of 40 million doses.

The scientists also criticised the drug-regulatory authorities for failing to ask for the full details of the clinical trials to be released before giving their approval.

In a searing indictment of the opacity of the pharmaceuticals industry, the ineffectiveness of the drug-regulatory process and the gullibility of politicians and government scientific advisers, the report delivers an excoriating account of one of the biggest drug scandals of the century.

The main authors of the report, compiled by the respected Cochrane Collaboration of independent medical scientists, advised the Government not to buy any further stocks of Tamiflu or Relenza to replace those in the stockpile that are coming to the end of their shelf life. They also urged the World Health Organisation to reconsider its recommendation for national stockpiles to combat an influenza pandemic.

Details buried within the 175,000 pages of clinical trials data held by the drug companies revealed that the only benefit of the anti-flu drugs was that they shortened the period of symptoms by about half a day. However, symptom relief was not the reason for justifying an expensive stockpile by the Government.

There was no evidence within the thousands of pages of clinical trial data to support the official rationale for the stockpile, namely that the drugs prevented dangerous complications such as pneumonia and slowed down the transmission of the virus within the population.

"The symptom relief is about half a day, but the indications are that the symptom relief is no better than medications you can get over the counter," said Carl Heneghan, professor of evidence-based medicine at the University of Oxford and one of the study's lead authors.

"There is no credible way that these drugs could prevent a pandemic. You'd have to treat 80 per cent of the population for eight weeks and have a vaccine immediately available even if you assume that it actually does work," Professor Heneghan said.

More worrying, however, was the evidence indicating that Tamiflu - which makes up about 85 per cent of the stockpile - when taken as a preventative medicine may result in serious side effects, such as kidney problems, high blood sugar and psychiatric disorders such as depression and delirium.

"The idea of a drug is that the benefit should exceed the harm. If you can't find a benefit, then you accentuate the harm," Professor Heneghan said. In Japan there have been cases of children harming themselves after taking the drug, he added.

These side effects and the bias placed on the benefits of the drugs should have been picked up by the regulatory authorities, namely the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice), which are responsible for drug approval and licensing.

"Once a drug goes into the marketing stage, most of the science goes out of the window so it's the regulators' job to go in there and be really tough and ask for all the evidence - and that has not occurred," Professor Heneghan said.

As a result, more than £600m of taxpayers' money has been "thrown down the drain" on a stockpile of anti-viral influenza drugs that effectively do not work as billed and can cause serious side-effects in a significant minority of people, he added.

Fiona Godlee, editor-in-chief of the British Medical Journal (BMJ), who has led the campaign for more openness from the drugs industry, said: "The current system isn't working. There is an irreducible conflict of interest that the pharmaceutical companies have. They manufacture these drugs and they have a duty to their shareholders to make a profit.

"It's not in their interests to create a clear picture of the drug. We have evidence again and again that the published evidence is biased and over optimistic about the benefits, and yet understates the harm," she added.

It took more than four years of arduous negotiations to convince the Swiss company Roche, which makes Tamiflu, and the British firm GSK, the manufacturers of Relenza - a powder taken by inhalation - to release the full details of their 46 clinical trials to the Cochrane collaboration.

After years of stonewalling, GSK relented with its full submission of its 26 Relenza trials last year, which was soon followed by Roche's release of its 20 Tamiflu trials.

Tom Jefferson, an epidemiologist and former GP who was the lead author of the study, said that the EMA approved Tamiflu - an oral tablet - on the basis of 16 clinical study reports provided by the company, of which only one was complete, the rest being either a summary or incomplete.

"That is not [the fault of] Roche. The EMA had the legal power to demand the full set, to demand anything they wanted, to inspect anything they want. It isn't Roche, it's the EMA, it's the regulators," Dr Jefferson said.

Daniel Thurley, UK medical director of Roche, said: "We disagree with the overall conclusions of this report. Roche stands behind the wealth of data for Tamiflu and the decisions of public health agencies worldwide."

A spokeswoman for the Department of Health said: "Tamiflu is licensed around the world for the treatment of seasonal flu and is a licensed product with a proven record of safety, quality and efficacy. We regularly review all published data and will consider the Cochrane review closely."

A spokeswoman for GSK said: "We continue to believe the data from Relenza's clinical trial programme support its effectiveness against flu and that when used appropriately, in the right patient, it can reduce duration of flu symptoms."

The drugs

Tamiflu and Relenza work in a similar way by blocking a vital enzyme of the influenza virus, called neuraminidase, which enables the virus to reproduce by budding off from the host cells that it infects.

However, the two neuraminidase inhibitors are very different from one another. Tamiflu, made by the Swiss company Roche and known by its generic name of oseltamivir, is taken as an oral pill, whilst Relenza (zanamivir), made by GSK, is inhaled as a powder, which limits its usefulness.

Relenza was the first neuraminidase on the market, but Tamiflu came along a few months later and quickly became the anti-flu pill of choice. About 85 per cent of the UK's national anti-flu drug stockpile is Tamiflu, with the remainder being Relenza, which is kept in case of resistance.

In 2007, Japan's Health Ministry reported that a number of children had been injured or killed after taking Tamiflu, some by jumping from buildings or falling in front of moving vehicles.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter