You are lying down with your head in a noisy and tightfitting fMRI brain scanner, which is unnerving in itself. You agreed to take part in this experiment, and at first the psychologists in charge seemed nice.

They set you some rather confusing maths problems to solve against the clock, and you are doing your best, but they aren't happy. "Can you please concentrate a little better?" they keep saying into your headphones. Or, "You are among the worst performing individuals to have been studied in this laboratory." Helpful things like that. It is a relief when time runs out.

Few people would enjoy this experience, and indeed the volunteers who underwent it were monitored to make sure they had a stressful time. Their minor suffering, however, provided data for what became a major study, and a global news story. The researchers, led by Dr Andreas Meyer-Lindenberg of the Central Institute of Mental Health in Mannheim, Germany, were trying to find out more about how the brains of different people handle stress. They discovered that city dwellers' brains, compared with people who live in the countryside, seem not to handle it so well.

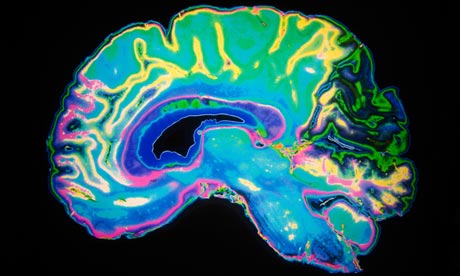

To be specific, while Meyer-Lindenberg and his accomplices were stressing out their subjects, they were looking at two brain regions: the amygdalas and the perigenual anterior cingulate cortex (pACC). The amygdalas are known to be involved in assessing threats and generating fear, while the pACC in turn helps to regulate the amygdalas. In stressed citydwellers, the amygdalas appeared more active on the scanner; in people who lived in small towns, less so; in people who lived in the countryside, least of all.

And something even more intriguing was happening in the pACC. Here the important relationship was not with where the the subjects lived at the time, but where they grew up. Again, those with rural childhoods showed the least active pACCs, those with urban ones the most. In the urban group moreover, there seemed not to be the same smooth connection between the behaviour of the two brain regions that was observed in the others. An erratic link between the pACC and the amygdalas is often seen in those with schizophrenia too. And schizophrenic people are much more likely to live in cities.

When the results were published in Nature, in 2011, media all over the world hailed the study as proof that cities send us mad. Of course it proved no such thing - but it did suggest it. Even allowing for all the usual caveats about the limitations of fMRI imaging, the small size of the study group and the huge holes that still remained in our understanding, the results offered a tempting glimpse at the kind of urban warping of our minds that some people, at least, have linked to city life since the days of Sodom and Gomorrah.

The year before the Meyer-Lindenberg study was published, the existence of that link had been established still more firmly by a group of Dutch researchers led by Dr Jaap Peen. In their meta-analysis (essentially a pooling together of many other pieces of research) they found that living in a city roughly doubles the risk of schizophrenia - around the same level of danger that is added by smoking a lot of cannabis as a teenager.

At the same time urban living was found to raise the risk of anxiety disorders and mood disorders by 21% and 39% respectively. Interestingly, however, a person's risk of addiction disorders seemed not to be affected by where they live. At one time it was considered that those at risk of mental illness were just more likely to move to cities, but other research has now more or less ruled that out.

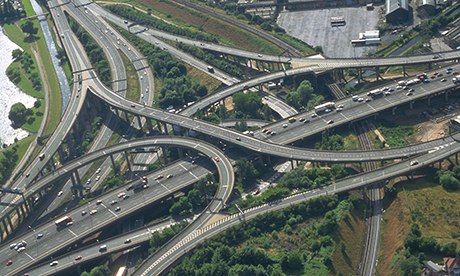

So why is it that the larger the settlement you live in, the more likely you are to become mentally ill? Another German researcher and clinician, Dr Mazda Adli, is a keen advocate of one theory, which implicates that most paradoxical urban mixture: loneliness in crowds. "Obviously our brains are not perfectly shaped for living in urban environments," Adli says. "In my view, if social density and social isolation come at the same time and hit high-risk individuals ... then city-stress related mental illness can be the consequence."

Meanwhile, a group of researchers at Hammersmith hospital, in London, are among many who believe that dopamine could hold the answer. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter with many functions, one of which is to infuse your brain when something important - good or bad - is happening. It might be that you are tasting an ice cream and your body wants you to eat the lot while you can, or it might be that a volcano is erupting and your body wants you to find your car keys nice and promptly. Dopamine levels are often very high in parts of schizophrenic peoples' brains.

Cities, the theory goes, might be part of the reason why a person's dopamine production starts to go wrong in the first place. Repeated stress is thought to lead to this problem in some people, so if high social density combined with social isolation could be shown to do so, and thus to alter the dopamine system, we might have the first rough sketches of a map from city living all the way to schizophrenia, and perhaps other things.

Thus far, nobody has shown that. And Bloomfield's team, led by Dr Oliver Howes, are being hampered in their attempts to do so by a shortage of volunteers who live in small towns or in the countyside. (If you'd be willing to step forward, please email him at michael.bloomfield@csc.mrc.ac.uk. They'll reimburse you for your time.) When you consider that stress is involved in some of schizophrenia's other known risk factors, such as being an immigrant and experiencing psychological trauma, it does look like a good theory.

In this field, a lot is at stake. Schizophrenia is already one of the leading causes of disability worldwide, and its prevalence looks likely to increase. In 2010, the proportion of the world's population living in cities passed gently into the majority. In 2050, according to UN projections, it is going to pass two-thirds.

Many other possible impacts of city living on brain function are also being investigated. Aircraft noise might inhibit children's learning, according to a recent study from Queen Mary University in London. (Although traffic noise, perversely, might help it.) Researchers in the US and elsewhere have also found that exposure to nature seems to offer a variety of beneficial effects to city dwellers, from improving mood and memory, to alleviating ADHD in children. Much of this research considers the question of "cognitive load", the wearying of a person's brain by too much stimulation, which is thought to weaken some functions such as self-control, and perhaps even contribute to higher rates of violence. In terms of its impact on public health, Adli believes that urbanisation may even be comparable to climate change.

Yet this is a change that we are choosing. As Adli himself is keen to emphasise, stress is only part of the impact that cities have on our brains. "There's a lot of what we call urban advantage," he says, "When we live in cities there is a much richer environment. There is also better healthcare, better education, a better standard of living. All these are protective factors."

Indeed for those people at lower risk, which may well be most of us, city life might even be indirectly beneficial for our mental health. For instance, being cuddled, played with and generally well cared for by your parents is powerfully associated with fewer social and emotional problems in later life. But, as Professor Sir Michael Marmot of University College London points out, "these various parenting activities do follow the social gradient. The lower the income the less likely you are to engage in them, and the more likely your children are to have social and emotional difficulties."

He also cites unemployment specifically as very damaging. Choose to live in the countryside, in short, and it might actually damage your family's mental health - and all-round health - if it costs you your job or makes you poorer. Perhaps Meyer-Lindenberg reminded his subjects of that fact when they collected their fee.

What is missing from cities is undisturbed nature - lots of trees - and clean air. Basically cities should be Un-Made, dismantled and forgotten forever.

It seems merging human consciousness with the aura of trees heals and relaxes.

Acidic-toxic city air eats away your lungs and kills you slowly, but surely. In a couple of years city-life can collapse your health, compared to what you had while living in the country.