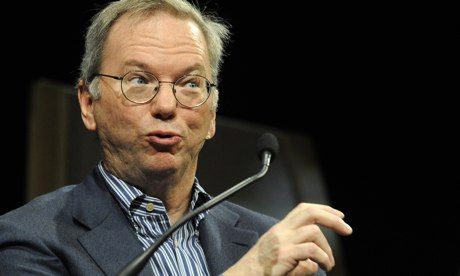

Google's executive chairman, Eric Schmidt, has insisted he had no knowledge of the US National Security Agency's tapping of the company's data, despite having a sufficiently high security clearance to have been told.

He said that he and other members of the search company were outraged by the tapping carried out by the NSA and the UK's GCHQ - first revealed in the Guardian in June - and that they had "complained at great length" to the US government over the intrusion. Google had since begun encrypting internal traffic to prevent further spying, he said.

Speaking in a private session at the Guardian, Schmidt, 58, said: "I have the necessary clearances to have been told, as do other executives in the company, but none of us were briefed.

"Had we been briefed, we probably couldn't have acted on it, because we'd have known about it. I've declined briefings [from the US government] about this because I don't want to be constrained."

But Schmidt, who was Google's chief executive from 2001 to April 2011, was equivocal on the question of a pardon for Edward Snowden, the former NSA contractor who leaked the documents that led to the revelations. "Had this information not come to light, we would not have been able to [stop the NSA spying]. I can understand the position he felt," said Schmidt, who revealed that he had protested against the Vietnam war as a young man. But on the question of whether Snowden should be pardoned or jailed, he said: "I don't think it's so obvious one way or the other."

Schmidt hinted that the number of requests for data filed by the NSA is small: "It's illegal to notify the public how many requests we get; we've filed suit to release the aggregate number. You can imagine why." He said that although he had clearance, and could if he chose see the requests filed through the standing court for NSA access to data, "I do not by choice, because if I did then I would be subject to a whole lot of rules. There's a team of attorneys who see them."

He said that the broad debate about the level of oversight there should be on government surveillance was "a luxury problem" compared with countries such as China, which operate strict censorship of internet use.

Schmidt predicted that China's adoption of smartphones and social networks such as Weibo and WeChat, which have around 300 million users each, would eventually overwhelm its government's ability to censor online discussion there. "You can't heavily censor that many people all the time. They don't understand the power of empowering a hundred million Chinese, no matter how brutal they're going to be with the bloggers."

He said that people in countries such as Myanmar, where only 1% of the population has access to the internet, were hungry for the capability it offers. "We went there and kept meeting people who hadn't used the internet but told us how it was going to change their lives and make them rich. It was the vision of the internet that we in the west know, not the one that they have in China even though it's right next door to them.

"The fact is that for most of the world's population, the next five billion, the internet is first going to be a set of ideas that permeates their society months or years before they ever use it as a tool. People are aware that there's all this information out there and they're being excluded from it, either because of economic reasons or their government. And humans don't deal well with a situation where they're denied access to information."

Schmidt also acknowledged that his "humanitarian mission" to North Korea in January 2013 could be seen as controversial. But he indicated that he was under no illusions about his welcome there. "Everyone you meet, everyone you see in the street, is an actor," he said.

But the reality of the desperation of North Korean life was evident from the efforts people made to contact the outside world by heading to its frontiers with smuggled mobile phones to get a signal and make calls. "They know that the penalty for being caught is that they will persecute your family for three generations," he said. "Yet they do it because it is so important to them to communicate."

'Do you eat with your smartphone on the table?'

Eric Schmidt's newest and biggest challenge sounds easy enough: get through dinner without looking at his smartphone or computer. "It's important to have defined times when you're on and off. I'm trying to turn my computer off when it's dinner," he told an audience at the Guardian. "I'm actually trying to establish the basic principle that dinner can be eaten without being online. It's a new social norm: do you eat with your smartphone on the table?"

The executive chairman of Google, 58, said that he didn't use social media such as Twitter much - despite having a Twitter account - but "there's always something on the internet that's interesting."

He said though that the rise of tablets could have profound effects. "I watched my grandson at Christmas, and he never turned the TV on - he just spent the whole time on his tablet. And I wondered, 'have I just seen the death of television?'"

It would seem that the cozy relationship was bait, as Google now finds itself thrown to the dogs of the NSA.

Power is not shared, as the Birds of a Feather who hold Power have insatiable appetites.

Encryption? Good luck. They will still spy on you, storing your data until they crack the encryption. Run, Google, run.