The story was broken yesterday by WSJ as part of a series called "The Lobotomy Files: Forgotten Soldiers."

The VA doctors considered themselves conservative in using lobotomy. Nevertheless, desperate for effective psychiatric treatments, they carried out the surgery at VA hospitals spanning the country, from Oregon to Massachusetts, Alabama to South Dakota.

The VA's practice, described in depth here for the first time, sometimes brought veterans relief from their inner demons. Often, however, the surgery left them little more than overgrown children, unable to care for themselves. Many suffered seizures, amnesia and loss of motor skills. Some died from the operation itself. This is not news in the sense of having been previously unknown. Rather, as the title suggests, we've simply let it slip down the memory hole.

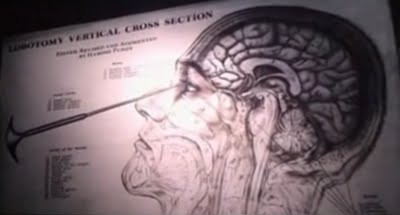

The VA's use of lobotomy, in which doctors severed connections between parts of the brain then thought to control emotions, was known in medical circles in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and is occasionally cited in medical texts. But the VA's practice, never widely publicized, long ago slipped from public view. Even the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs says it possesses no records detailing the creation and breadth of its lobotomy program.

When told about the program recently, the VA issued a written response: "In the late 1940s and into the 1950s, VA and other physicians throughout the United States and the world debated the utility of lobotomies. The procedure became available to severely ill patients who had not improved with other treatments. Within a few years, the procedure disappeared within VA, and across the United States, as safer and more effective treatments were developed."

Musty files warehoused in the National Archives show VA doctors resorting to brain surgery as they struggled with a vexing question that absorbs America to this day: How best to treat the psychological crises that afflict soldiers returning from combat.

Between April 1, 1947, and Sept. 30, 1950, VA doctors lobotomized 1,464 veterans at 50 hospitals authorized to perform the surgery, according to agency documents rediscovered by the Journal. Scores of records from 22 of those hospitals list another 466 lobotomies performed outside that time period, bringing the total documented operations to 1,930. Gaps in the records suggest that hundreds of additional operations likely took place at other VA facilities. The vast majority of the patients were men, although some female veterans underwent VA lobotomies, as well.

Lobotomies faded from use after the first major antipsychotic drug, Thorazine, hit the market in the mid-1950s, revolutionizing mental-health care. The main focus of the WSJ feature, rightly, is on the individuals whose lives were destroyed by this barbaric treatment. That's a genuine tragedy. The professional charge of physicians, predating by centuries the professionalization of physicians, is to "do no harm." The VA doctors failed in that duty with heartbreaking consequences.

But this is not another example of government doctors treating our soldiers as subhuman guinea pigs. This is not another Tuskegee Experiment. It was, in fact, the opposite. The VA was applying state-of-the-art medicine with great compassion. Unfortunately, the Dark Ages of mental health treatment ended in living memory; indeed, it's quite possible they haven't actually ended.

Comment: Barbaric and compassionate? There is nothing compassionate about driving a surgical instrument through the eye socket between the upper lid and eye. It IS barbaric, cruel and sick. Normalizing such atrocities is called Ponerization; from ancient Greek poneros ("evil"), is a term created by Dr. Andrzej M. Łobaczewski as part of ponerology, the scientific study of macrosocial evil. Ponerization is the influence of pathological people on individuals and groups whereby they develop acceptance of pathological reasoning and other pathological characteristics.

What does it mean to be "ponerized"? When something or someone has become "ponerized" in its strictest sense, it means that the person or group can no longer make the distinction between healthy and pathological thought processes and logic. One is no longer able to draw a line between correct thinking and deviate thinking.

When World War II began, the U.S. military thought it knew how to stave off the psychiatric issues that had ravaged men in the trenches in the previous world war. It began screening potential recruits for psychological trouble signs and ultimately rejected some 1.8 million American men for World War II service on that basis.

Nevertheless, the military and VA soon found their hospitals overflowing. A 1955 National Research Council study counted 1.2 million active-duty troops admitted to military hospitals during the war itself for psychiatric and neurological wounds, compared with 680,000 for battle injuries.

Desperate for an effective treatment for the worst-off patients (including some mentally ill World War I veterans) the VA embraced lobotomy. At the time, tens of thousands of the procedures were being performed in civilian hospitals, a wave inspired by two of lobotomy's most avid promoters, neurologist Walter Freeman and neurosurgeon James Watts.

"In practical use, the operation has been found of value in eliminating apprehension, anxiety, depression and compulsions and obsessions with a marked emotional content," VA Assistant Administrator George Ijams wrote to his boss in July 1943, urging the agency to approve the procedure.

Within a month, VA headquarters set guidelines. It ordered doctors to limit lobotomies to cases "in which other types of treatment, including shock therapy, have failed" and to seek permission of the patient's nearest relative.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, there existed no diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder, a term that came into vogue after the Vietnam War. Back then, the term was "shell shock" or "battle fatigue." Many lobotomy patients, however, exhibited symptoms that might now be classified as PTSD, says Dr. Valenstein, the former VA psychiatrist.

"Realistically looking back, the diagnosis didn't really matter - it was the behaviors," says psychiatrist Max Fink, 90, who ran a ward in a Kentucky Army hospital in the mid-1940s. He says veterans who couldn't be controlled through any other technique would sometimes be referred for a lobotomy.

"I didn't think we knew enough to pick people for lobotomies or not," says Dr. Fink. "It's just that we didn't have anything else to do for them."

Wikipedia notes that, "The originator of the procedure, António Egas Moniz, shared the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine of 1949 for the 'discovery of the therapeutic value of leucotomy [the then-accepted name for the practice] in certain psychoses.'" Not surprisingly, then, "he use of the procedure increased dramatically in some countries from the early 1940s and into the 1950s; by 1951, almost 20,000 lobotomies had been performed in the United States. Following the introduction of antipsychotic medications in the mid-1950s lobotomy underwent a gradual but definite decline."

Indeed, lobotomy wasn't the only barbarous mental health procedure of the era:

In the early 20th century, the number of patients residing in mental hospitals increased significantly[n 2] while little in the way of effective medical treatment was available.[n 3][9] Lobotomy was one of a series of radical and invasive physical therapies developed in Europe at this time which signaled a break with a psychiatric culture of therapeutic nihilism that had prevailed since the late nineteenth-century.[10] The new "heroic" physical therapies devised during this experimental era,[11] including malarial therapy for general paresis of the insane (1917),[12]deep sleep therapy (1920), insulin shock therapy (1933),cardiazol shock therapy (1934), and electroconvulsive therapy (1938),[13] helped to imbue the then therapeutically moribund and demoralised psychiatric profession with a renewed sense of optimism in the curability of insanity and the potency of their craft.[14] The success of the shock therapies, despite the considerable risk they posed to patients, also helped to accommodate psychiatrists to ever more drastic forms of medical intervention, including lobotomy.[11]So, while the "forgotten soldiers" story is awful, it's not outrageous. It's simply a reflection of a much different, if nonetheless quite recent, time.

The clinician-historian Joel Braslow argues that from malarial therapy onward to lobotomy, physical psychiatric therapies "spiral closer and closer to the interior of the brain" with this organ increasingly taking "center stage as a source of disease and site of cure."[15] For Roy Porter, once "the doyen" of medical history,[16] the often violent and invasive psychiatric interventions developed during the 1930s and 1940s are indicative of both the well-intentioned desire of psychiatrists to find some medical means of alleviating the suffering of the vast number of patients then in psychiatric hospitals and also the relative lack of social power of those same patients to resist the increasingly radical and even reckless interventions of asylum doctors.[17] From the perspective of the present, lobotomy has become a disparaged procedure, a byword for medical barbarism and an exemplary instance of the medical trampling of patients' rights.[18] This viewpoint is to ignore, however, the belief shared by many doctors, patients and family members of the period that, despite potentially catastrophic consequences, the results of lobotomy were seemingly positive in many instances or, at least, they were deemed as such when measured next to the apparent alternative of long-term institutionalisation. Lobotomy, if always controversial, was also for a time part of the medical mainstream, even feted, and regarded as a legitimate if desperate remedy for categories of patients who were otherwise regarded as hopeless.

Comment: The author may benefit from learning about psychopaths and ponerology. "One phenomenon all ponerogenic groups and associations have in common is the fact that their members lose (or have already lost) the capacity to perceive pathological individuals as such, interpreting their behavior in a fascinated, heroic, or melodramatic way. The opinions, ideas, and judgments of people carrying various psychological deficits are endowed with an importance at least equal to that of outstanding individuals among normal people. The atrophy of natural critical faculties with respect to pathological individuals becomes an opening to their activities, and at the same time a criterion for recognizing the association in concert as ponerogenic. Let us call this the first criterion of ponerogenesis."