Now, further investigation has revealed the dolphin's malaise was caused by a virus that scientists had never seen before, according to a new study.

The pathogen, which researchers propose should be named Dolphin polyomavirus 1, or DPyV-1, is still quite mysterious.

Scientists say they don't know where it came from, how common it might be, or what threat it poses to wildlife.

Comment: Here are couple of articles for the reader to ponder about the possible source of the virus and kind of dangers or outcomes this possibility represents:

New Light on the Black Death: The Viral and Cosmic Connection

On viral 'junk' DNA, a DNA-enhancing Ketogenic diet, and cometary kicks

"We don't even know if this is even a dolphin virus. It could also represent a spillover event from another species," Simon Anthony, a researcher who studies wildlife pathogens at Columbia University, said in a statement.

"It's no immediate cause for alarm, but it's an important data point in understanding this family of viruses and the diseases they cause."

Genetic analysis showed that the polyomavirus found in the San Diego dolphin was distinct from other known polyomaviruses (a widespread family of small DNA viruses that can sometimes cause infections and tumors in various animals).

The pathogen appeared to be most closely related to the California sea lion polyomavirus, the researchers reported online on July 10 in the journal PLOS ONE.

"It's possible that many dolphins carry this virus or other polyomaviruses without significant problems," said Judy St. Leger, the director of pathology at SeaWorld in San Diego, who performed the initial animal autopsy (or necropsy) on the stranded dolphin.

"Or perhaps it's like the common cold, where they get sick for a short while and recover," St. Leger added in a statement.

The researchers say they do not know of any other cases resembling the stranded dolphin in San Diego, but they are searching for more examples of polyomavirus in the species. The team hopes to determine the prevalence of DPyV-1 in short-beaked common dolphins and find out if it represents a significant source of dolphin illness and mortality.

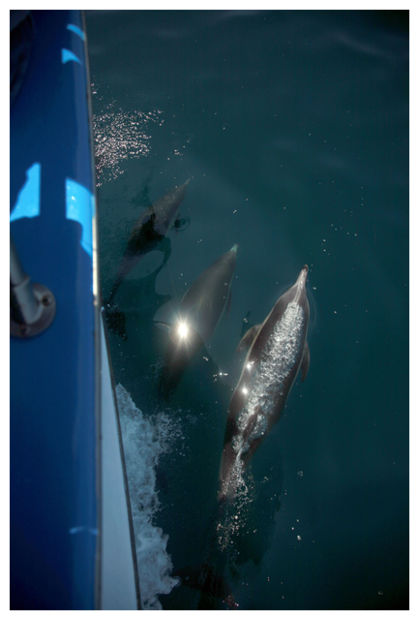

Understanding how viruses develop in marine mammals is important for protecting endangered species, whose populations could nosedive if they are hit by a deadly outbreak. And marine mammals can pick up pathogens that originated in other animals, even humans.

Canine distemper virus, for example, has caused sickness in seals and polar bears (often considered marine mammals since they spend much of their time at sea). A strain of bird flu was blamed for a mass die-off of New England harbor seals in 2011. Earlier this year, researchers found that a group of northern elephant seals off the coast of central California was carrying the H1N1 virus strain, which caused a swine flu outbreak in humans in 2009. The seals could have caught the species-jumping pathogen from human feces dumped out of shipping vessels or seabirds, the scientists speculated at the time.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter