© Layne Kennedy/CORBISMemorial Arch and building at Oberlin College.

Ohio's Oberlin College recently cancelled classes after someone reported spotting a person walking on campus wearing what appeared to be a Ku Klux Klan-like hooded robe at night. College officials released a statement on Monday explaining that "This event, in addition to the series of other hate-related incidents on campus, has precipitated our decision to suspend formal classes and all non-essential activities ... and gather for a series of discussions of the challenging issues that have faced our community in recent weeks."

What of the uniformed Klansman spotted on campus? According to

a piece on Slate.com, "Local police responded to the report, but weren't able to find anyone wearing the hard-to-miss KKK garb. They did, however, discover a female walking with a blanket wrapped around her, suggesting the very real possibility that the eyewitness was mistaken."

The

Chronicle-Telegram added, "Oberlin police Lt. Mike McCloskey said that authorities did find a pedestrian wrapped in a blanket. He said police interviewed another witness later in the day and that person also saw a female walking with a blanket."

In retrospect - and in the cold light of day - it's much more likely that a person on campus was wearing or carrying a light-colored blanket, coming back from a toga party, or even a prankster dressed like a ghost, instead of dressed in full Klan regalia. But why would someone make that particular mistake? The answer lies in what psychologists call expectant attention and confirmation bias.

Expectation Influences PerceptionThough many people assume that eyewitnesses accurately perceive, understand, and report what they experience, we are subject to several biases. And they influence us in ways we often aren't unconsciously aware of.

In order to make sense of what we see - especially things we don't recognize or fully understand - the human brain looks for contextual cues. We look for what else is going on in the environment that might lead to one interpretation instead of another.

© Discovery News

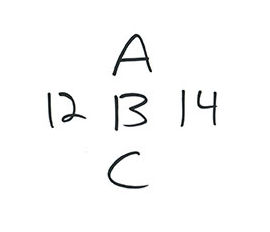

One powerful influence on our perceptions is our expectations. A well-known example of this can be seen in the image at right. The same ambiguous symbol can be interpreted in very different ways, depending on the context. Read vertically, the symbol in the middle of the picture can be easily read as the capital letter B, while read horizontally the symbol can be easily read as the number 13. Neither answer is wrong; both interpretations are correct within their context. But the context makes all the difference.

How does this apply to the Klansman seen at Oberlin College? There were at several contextual factors that led the eyewitness to associate the figure with the Klan. Most importantly, the campus had recently experienced a string of events characterized as hate crimes, with flyers and graffiti targeting African-Americans, gays, and Jews appearing on campus.

The events were widely reported and triggered much discussion on campus about the presence of hate groups. Most bald men are not skinheads, and racists can come in any race, gender, or color. But the most identifiable hate group - the only one with an image that is unmistakably associated with intolerance - is the Ku Klux Klan and their distinctive hoods and robes.

Secondly, the location played a role in the misidentification: The white-clad figure was not seen outside a local pizza place or library, but instead outside the Afrikan Heritage House, the building on campus most closely associated with African-Americans. It's unlikely that if the same woman had been seen outside a campus synagogue she would have been interpreted as a member of the Klan.

Then there's the fact that the eyewitness probably didn't know exactly what an actual KKK outfit looks like. Real Klan robes have a distinctive, specific cut to them, and typically a cross emblem on the front. The eyewitness only caught a glimpse of the person, in low light and early in the morning. Psychological studies have shown that under such conditions, the human mind is very poor at accurately perceiving, remembering, and reporting even basic elements of the experience.

Our brains often "fill in" details with what we expect to see - not necessarily what we actually see - and we tend to bias our reports accordingly. Thus a person wrapped in, or even carrying, a light-colored blanket can become a Klan outfit.

Though the sighting remains under investigation and it is possible that a lone hooded Klansman was seen past midnight walking on the Oberlin campus, it seems much more likely that the report was simply an eyewitness error.

Examples like this help remind us that sincere,

otherwise credible eyewitnesses can often be influenced by many factors, including what they expect to see. The idea that people often incorrectly see, remember, and report what they experience is not merely theory but a proven fact. There are over 2,000 published scientific studies demonstrating it. By some estimates, as many as 1/3 of eyewitness identifications in criminal cases are wrong, and nearly 200 people who were convicted of crimes based on positive eyewitness identifications were later exonerated through DNA evidence.

"No problem, just call the cops and say you think you saw someone with a gun; They'll cancel tomorrow's classes for you."