Murder inquiries may be misled or delayed by psychologists who see themselves as real-life Crackers, researchers claim.

Police forces routinely ask behavioural scientists to draw up profiles of killers who are still at large, based on a knowledge of the victim and details recorded at the crime scene.

But according to a team of psychologists at Birmingham City University, the practice of offender profiling is deeply unscientific and risks bringing the field into disrepute.

In many cases, offender profiles are so vague as to be meaningless, according to psychologist Craig Jackson. At best, they have little impact on murder investigations; at worst they risk misleading investigators and waste police time, he said.

The Home Office holds a register of psychologists and other professionals who are qualified to give offender profiles to police forces after reviewing details of a crime.

"Behavioural profiling has never led to the direct apprehension of a serial killer, a murderer, or a spree killer, so it seems to have no real-world value," Jackson said.

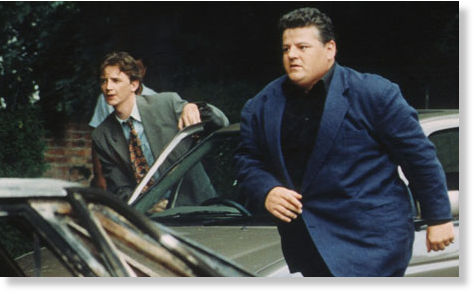

"It is given too much credibility as a scientific discipline. This is a serious issue that psychologists and behavioural scientists need to address," he said. "People believe psychologists like Cracker can exist." In the 1990s television series, police apprehended criminals with help from an overweight, chain-smoking alcoholic psychologist.

A report criticising offender profiling by Jackson and two colleagues will be published in the legal journal, Amicus, next month. He will describe his research at the British Science Festival in Birmingham this week.

Behavioural profiling became popular in the US in the 1970s when psychologists working with the FBI used questionnaires to interview 36 imprisoned serial killers. Their responses were used as a basis for drawing up profiles of future murderers.

Research since then has found that serial killers are unreliable interviewees, a realisation that undermines the foundations behavioural profiling was built on, Jackson claims.

The questionable nature of killers' testimonies was raised by John Bennett, senior investigating officer on the Fred West case in the mid-1990s. He noted that his interviews with West were "worthless, except to confirm that nothing he said could be relied upon as anything near the truth". In one exchange, West claimed he was a roadie with Lulu in the 1960s.

Behavioural scientists rarely have a major influence on the direction of murder inquiries, but Jackson said investigators can come under pressure to consult them to appease the media and victims' families.

Jackson quoted one behavioural scientist as saying he "climbs inside the minds of monsters" and "takes the expression frozen on the face of a murder victim and works backwards".

"They bring themselves forward as if they are shamans who are cursed by nightmares and picturing dead people," Jackson said.

Carol Ireland, vice chair of forensic psychology at the British Psychological Society, said offender profiling is not widely practised by forensic psychologists.

"Whatever we are doing as forensic psychologists, it should be based in science and theory. If it's not then we need to explore what we are doing. Ultimately we are scientist-practitioners," she said.

Offender profiling was first used in the UK in 1986, when psychologist David Canter drew up a description of the "Railway Rapist" and serial killer John Duffy. Canter, whose research centres on ways to make profiling more scientific, has contributed to more than 150 investigations.

Serial Killers might lie? Shocking!

"Research since then has found that serial killers are unreliable interviewees, a realisation that undermines the foundations behavioural profiling was built on . . ."

Well, "No Sh*t, Sherlock!"

But of course, the folks who ran those earlier studies who had their agenda going (to wit: get the government cash, even if it meant imprisoning innocents) so they didn't let common sense get in their way (such as the fact that serial killers might - indeed, would most likely - lie and/or have bad memories of their frankly illogical and therefore hard to remember motives)

That of course led to the conclusion (as supported and expressed in the other, absurd, propagandistic and anecdotal, at best, article linked today entitled "Dangerous Mind: Criminal Profiling made easy" ) that any idiot can be a Profiler, ... argh.

That gave us Law Enforcement Officers more than happy to Execute people for looking wrong; allowing themselves to believe that they have the ability, right and to percieve and DUTY TO KILL based upon merest "gut instinct," etc., (E.g., Brazilian shot and killed in U.K. Metro or poor Claustro/Acrophobic on plane shot and killed by Marshals in Miami) and even getting medals for it! (The Miami Nazis were so bejeweled by that guy who now makes O'Bushma look good; To(o) wit(less): W. Bush*t, II.)

R.C.