Mysterious fossils of what may be a previously unknown type of human have been uncovered in caves in China, ones that possess a highly unusual mix of bygone and modern human features, scientists reveal.

Surprisingly, the fossils are only between 11,500 and 14,500 years old. That means they would have shared the landscape with modern humans when China's earliest farmers were first appearing.

"These new fossils might be of a previously unknown species, one that survived until the very end of the ice age around 11,000 years ago," said researcher Darren Curnoe, a palaeoanthropologist at the University of New South Wales in Australia.

"Alternatively, they might represent a very early and previously unknown migration of modern humans out of Africa, a population who may not have contributed genetically to living people," Curnoe added.

The skeletons

At least three fossil specimens were uncovered in 1989 by miners quarrying limestone at Maludong or Red Deer Cave near the city of Mengzi in southwest China. They remained unstudied until 2008. The scientists are calling them the "Red Deer Cave People," because they cooked extinct red deer in their namesake cave.

Carbon dating, a technique that estimates the radioactive decay of carbon in samples of charcoal found with the fossils helped establish their age. The charcoal also showed they knew how to use fire. Stone artifacts found at the Maludong site also suggest they were toolmakers.

A Chinese geologist found a fourth partial skeleton, which looks very similar to the Maludong fossils, in a cave near the village of Longlin in southwest China in 1979 while prospecting the area for oil. It stayed encased in a block of rock neglected in the basement of an archaeological research institute until 2009, when the international team of scientists rediscovered the fossils.

"In 2009, when I was in China working with co-author Professor Ji Xueping, he showed me the block of rock that contained the skull," Curnoe recalled. "After picking my own jaw up from the floor, we decided we had to make the remains a priority of our research."

Jutting jaws and flaring cheeks

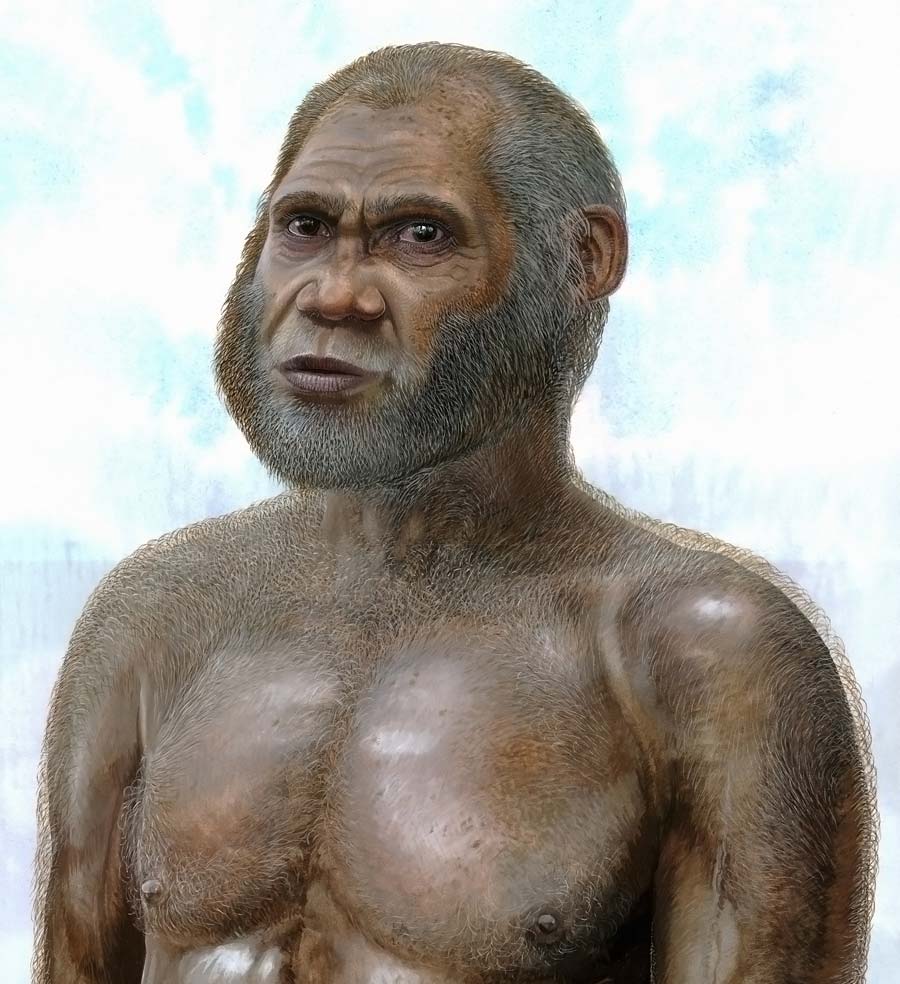

The Stone Age fossils are unusual mosaics of modern and archaic human anatomical features, as well as previously unseen characteristics. This makes them difficult to classify as either a new species or an unusual type of modern human.

However, the Red Deer Cave people differ from modern Homo sapiens in their prominent brow ridges, thick skull bones, flat upper faces with a broad nose, jutting jaws that lack a humanlike chin, brains moderate in size by ice age human standards, large molar teeth, and primitively short parietal lobes - brain lobes at the top of the head associated with sensory data. "These are primitive features seen in our ancestors hundreds of thousands of years ago," Curnoe said.

Unique features of the Red Deer Cave people seen neither in modern nor known archaic lineages of humans include a strongly curved forehead bone, very broad nose and eye sockets, and very flat cheeks that flare widely to the sides to make space for large chewing muscles. In addition, the place where the lower jaw forms a joint with the base of the skull is unusually wide and deep.

All in all, the Red Deer Cave people are the youngest population to be found anywhere in the world whose anatomy does not comfortably fit within the range of modern humans, whether they be modern humans from 150 or 150,000 years ago, the researchers noted.

"In short, they're anatomically unique among all members of the human evolutionary tree," Curnoe told LiveScience.

Mysterious population in Asia

The Red Deer Cave people lived in China at the end of the ice age. "They survived the final and one of the worst cold episodes, known as the Last Glacial Maximum, which ended around 20,000 years ago," Curnoe said.

"The period around 15,000 to 11,000 years ago when they thrived in southwest China is known as the Pleistocene-Holocene transition, and it saw a shift to climates and ecological communities the same as those of today," Curnoe added. "It also saw the demise of the megafauna in most places, including a giant deer that was exploited by the Red Deer Cave people and recovered in large numbers from the Maludong site."

"This time also saw a major shift in the behavior of modern humans in southern China, who began to make pottery for food storage and to gather wild rice - this marks some of the first steps towards full-blown farming," Curnoe said. "The Red Deer Cave people were sharing the landscape with these early pre-farming communities, but we have no idea yet how they may have interacted or whether they competed for resources."

Although modern-day Asia contains more than half of the world's population, researchers still know little about humans there after our ancestors settled Eurasia about 70,000 years ago, Curnoe said. No human fossils less than 100,000 years old had been found in mainland East Asia that resembled anything other than anatomically modern humans until now. These new findings are fossil evidence that this region may not have been devoid of our evolutionary cousins.

"The discovery of the Red Deer Cave People opens the next chapter in the latest stage of the human evolutionary story, the Asian chapter," Curnoe said. "It's a story that's just beginning to be told."

Defining a human

A key reason the scientists have not yet decided how to classify the Red Deer People scientifically has to do with one of the major ongoing questions for scientists investigating human evolution - "the lack of a satisfactory biological definition of our own species, Homo sapiens," Curnoe said. "We still don't have one that most of us agree upon."

"I think the evidence is slightly weighted towards the Red Deer Cave people representing a new evolutionary line," Curnoe said. "First, their skulls are anatomically unique - they look very different to all modern humans, whether alive today or in Africa 150,000 years ago. And second, the very fact they persisted until almost 11,000 years ago when we know that very modern-looking people lived at the same time immediately to the east and south suggests they must have been isolated from them. We might infer from this isolation that they either didn't interbreed or did so in a limited way."

Recent findings suggest that other, different evolutionary lines may have also lived in the region, such as the "hobbit" or Homo floresiensis on the island of Flores in Indonesia.

"This paints an amazing picture of diversity, one we had no clue about until this last decade," Curnoe said.

The Red Deer Cave people might possibly even be related to a mysterious branch of humanity known as the Denisovans only discovered in the past two years, whose DNA suggests they were neither like us nor Neanderthals.

"It is certainly possible that the Red Deer Cave people (represent) an interbreeding event between modern humans and some other population like the Denisovans," Curnoe said.

Ultimately, to see how closely or distantly related the Red Deer Cave people are to modern humans or even the Denisovans, the scientists want to extract and test DNA from the fossils. "We've had one attempt already, but without success," Curnoe said. "We'll just have to wait and see if we're successful in our future work."

The scientists detailed their findings online March 14 in the journal PLoS ONE.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter