© switchboard.nrdc.org

Higher prenatal exposure to an insecticide commonly used worldwide was associated with poorer motor development in the children at 2 years of age, suggesting that in utero carbamate pesticide exposures may have lasting consequences.

The study is one of the first to assess developmental affects of gestational exposure to the pesticide propoxur on children's growing nervous system. The study - which followed 696 children from the Philippines - is published online in the journal

Neurotoxicology.

A number of human studies have reported that gestational exposure to pesticides is associated with poorer mental development in children. Most of these prior studies have relied on the mother's exposure, which is typically measured in urine or by questionnaire. This new study is unique since it was able to directly measure the infants' pesticide exposure during gestation.

Assessing motor skills is important because their development may be sensitive to early life environmental chemical exposures. Impairments in motor skills can also impact how children learn as they grow older. For instance, slower fine motor control might delay children in being able to pick up and manipulate objects like pencils and crayons.

The researchers in this study used levels of propoxur in meconium - the infant's first stool - as a novel method to measure fetal exposure to pesticides. Meconium begins forming in the second trimester. Substances accumulate in it during the last two trimesters of pregnancy. This makes meconium very useful for measuring prebirth exposure to chemicals like pesticides and drugs of abuse.

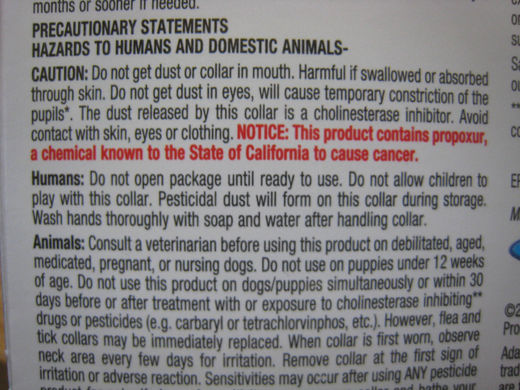

The pesticide propoxur is used to control fleas, mosquitoes, and other pests. Propoxur is a carbamate pesticide that works by inhibiting the acetylcholinesterase enzyme required for insect nerve cells to work. Human nerve cells also use acetylcholinesterase, and the pesticides might bind to and inhibit the enzyme in the developing infant's brain.

The investigators followed 696 infants for two years. After birth, cord blood, meconium and hair samples were collected and analyzed for a number of pesticides. When the children were 2, the researchers measured various aspects of the child's brain development, including motor, social, and visual-spatial skills. The researchers compared pesticide levels in the various samples with the developmental measures. They statistically controlled for other factors that might influence the results, such as gender, socioeconomic status, maternal intelligence, postnatal exposure to propoxur and blood lead levels at 2 years of age.

At birth, propoxur was detected in less than 2 percent of infant's hair and blood. However, about 21 percent of infants had detectable levels of propoxur in their meconium. Those infants had lower scores on measures of motor development two years later. Visual-spatial and social skills were not associated with propoxur exposure.

Future studies will need to determine if these deficits in motor performance persist into later childhood and whether exposure to pesticides affect other aspects of children's brain development.

Ostrea Jr, EM, A Reyes, E Villanueva-Uy, R Pacifico, B Benitez, E Ramos, RC Bernardo, CM Bielawski, V Delaney-Black, L Chiodo, JJ Janisse and JW Ager. 2011.

Fetal exposure to propoxur and abnormal child neurodevelopment at two years of age.

Neurotoxicology

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter