© SecurityNewsDaily

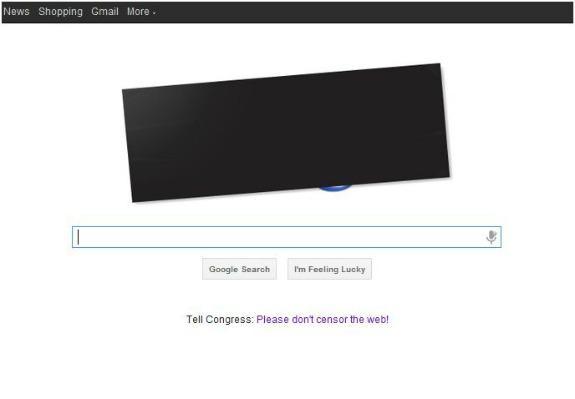

Wondering what happened to Wikipedia yesterday (Jan. 18)? Perhaps you heard it was a protest against legislation with the vague name SOPA and arguments about a lot of other acronyms like ISP and DNS. You could read all day about the technical and legislative intricacies. But here is the dystopian scenario that SOPA's opponents fear:

You're talking with friends about

Avatar and whether it was Zoe Saldana's first lead role. To find out, you do a Web search for her name and get a set of links - none of them to Wikipedia. In fact, the only sites you see are from the movie studio.

What happened? The domain-name servers that your computer uses to look up the addresses of websites have been modified, by law, so many sites don't show up. They have "disappeared" from the

Internet like characters out of Orwell, and you are none the wiser.

One of those blocked sites belongs to a blogger who reviewed the movie. He asks his Internet-service provider why traffic has suddenly gone to zero and discovers that someone complained about him linking to a site with pirated content - say, a movie clip on

YouTube. To avoid getting sued and possibly shut down, the service provider simply blocked the blogger's site, without telling him. The blogger can appeal the decision, but in the meantime his site is offline, and his income from advertising dries up.

In the apartment downstairs, meanwhile, a human-rights activist wants to tell people in China and Iran how to get around the censorship imposed by their countries' Internet filtering systems. But she can't. Technology used to slip by censors can also be used to get around the site-blocking required by the new

anti-piracy laws. A website can be shut down if it is distributing any technology that could be used to infringe copyrights.

Want to upload that cool video to YouTube? What YouTube? The site was told that it was hosting "infringing content," meaning a few people among its millions of users uploaded copyrighted videos. Since Google was an "intermediary" - the host - it is required to take action. In this case it would be policing every user to check for pirated content.

But enough letters came in from copyright lawyers that the site was forced to simply shut down - at least in the United States. And you can't get to the foreign-based YouTube sites either, because the U.S. attorney general has issued an order essentially erasing them from the domain-name-system servers.

These are extreme examples, and certainly not what legislators predict would happen. But critics - who include essentially the entire tech industry - believe these could be the kinds of results from the current versions of the

Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) working its way through the U.S. House of Representatives and its sister bill in the Senate, the PROTECT-IP Act (PIPA).

Both bills have a provision saying that, if a U.S.-based user types in the Web address of an infringing site, the domain-name server at the user's Internet service provider (ISP) would be forbidden from giving the correct address to the user's browser.

Basically, you would get a classic "404" message that said the site was down, but that would be incorrect. The site would be up and running, but you would be blocked from reaching it. The legislation that makes this possible is written specifically to block non-U.S. infringing websites, but critics fear it could affect any site.

Those draconian measures may change, though. SOPA's sponsor, House Judiciary Committee Chairman Lamar Smith (R-Tex.), now says he plans to remove the language that requires ISPs to block access to websites accused of infringing copyrights. But even if that happens, it won't be until next month.

The next big action will be Jan. 24, when a Senate committee votes on bringing its version of the bill, PIPA, to the full chamber. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) has said the bill, which still has its own website-blocking provisions, will move forward.

...called "common carrier." A common carrier couldn't be held liable for the traffic carried by it.

For instance, if two people in a telephone conversation plan a bank robbery, then the telephone company cannot be held liable for that illegal activity. The content of a telephone conversation is not the responsibility of the telephone company.

The same "common carrier" standard should apply to Internet sites. Action against an Internet site should be undertaken only after the site has refused to remove illegal content.

SOPA is just one more tightening of the "guilty until proved innocent" screw.