Neuroscience is already making waves in court: an Italian woman convicted of murder recently had her sentence reduced on the grounds that her behaviour could be explained by abnormalities in her brain and genes.

The authors on the Royal Society panel, led by Nicholas Mackintosh of the University of Cambridge, also flag up research that suggests the brains of psychopaths are fundamentally different. This raises the question: should individuals with the brain anatomy of a psychopath have their sentence reduced on the ground of diminished responsibility, or should brain scan evidence be used to keep dangerous individuals locked away?

Perhaps one day we may also be able to find neurological clues that help predict whether a criminal is likely to reoffend. The report only goes so far as to suggest that such information may be useful in conjunction with other evidence.

Another key issue is that of the age of criminal responsibility. In England, the age at which a child can be tried as an adult is ten - this is too low, say the report's authors.

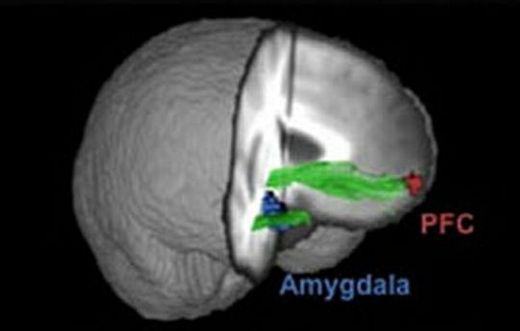

Recent research into brain development suggests that crucial brain regions - such as the prefrontal cortex, which is important in decision making and impulse control - don't actually finish maturing until the age of around 20.

Neuroscientists claim to be able to identify certain patterns of brain activity that are associated with lying, a finding that has raised the possibility of brain scan-based lie detection. But many remain skeptical that such an approach can ever be useful in the legal setting.

Lie detection research is often based on students telling untruths that are unlikely to have any impact on their lives - a situation that's difficult to compare to a criminal who might be lying for his life, not to mention that of a cunningly deceptive psychopath. Moreover, as the report points out, if such lie detection were possible, it wouldn't detect when a person was telling a falsehood they believed was true, or whether a person had learned how to trick the system.

"In one experiment, the success rate for distinguishing truth from lies dropped from 100 per cent to 33 per cent when participants used countermeasures," say the authors. They conclude that "for the foreseeable future reliable fMRI lie detection is not a realistic prospect."In the same vein, attempts to measure the amount of pain that a person is in - perhaps to catch people who cheat on health insurance payouts - could also be foiled by individuals who learn how to simulate the brain activity associated with the experience of pain, the authors say.

And then there's that old chestnut: "my brain made me do it". In some cases it seems the argument can be made. For one man, paedophilic tendencies appeared and disappeared with a tumour in his orbitofrontal cortex - a region linked to judgement and social behaviour.

Most cases aren't so clear cut. The report concludes by recommending that neuroscientists and lawyers from around the globe meet to discuss the latest in each discipline once every three years.

In the meantime, the authors recommend that the legal system consult with groups such as the British Neuroscience Association to assess how lawyers currently access scientific expertise. The authors also reckon it would be useful for law degrees to include some background in neuroscience, and for neuroscientists in training to consider the societal applications of their science.

In all this time we have found no better way to handle illegal behavior than prison for criminal offenders and fines for civil offenders. There is very little evidence to indicate that these handlings actually change or improve behavior. But we continue to see them as the standard thing to do.

Some new ways to handle prisoners that seem to rehabilitate many of them are being jumped on by a few prison officials that want better answers, but ignored by most.

And evidence that there are ways to reduce or eliminate the urge to behave in a criminal manner is also ignored.

Society seems totally resigned to the existence of criminality in its midst. So the criminals are saying: Why bother punishing us? Its all in our genes anyway, so there's nothing we can do about it. This is a total and utter lie. But people are taking these suggestions seriously!

Why don't we just give up on law entirely? It's a failed device. It could probably be argued that there is no evidence that laws make life better. But I don't think that argument would be correct.

Public and explicit rules that are uniformly enforced on all players open up a game to more players. So they are a good thing. The usual punishment for repeatedly breaking the rules is to be kicked out of the game. I guess that's what prison tries to do. So the obvious thing to do in prison is to teach the prisoners what the rules are so that they can play without breaking the rules so often. Right?

Psychopaths are another issue. Our main problem with them is that they have already infiltrated and corrupted most institutions of society. In this case, people of goodwill must be willing to take it upon themselves to expose criminals hiding behind positions of authority. This is currently society's biggest challenge. The brain scan idea just won't work. Exposure has to be in the from of solid evidence of evil intentions acted upon.