In research that casts a shadow on the otherwise helpful role of symbiotic gut bacteria, U.S. scientists found that at least three viruses - polio, a reovirus and mouse mammary tumour virus - were severely impeded from transmitting or replicating in mice without the help of intestinal germs to slip past the body's defences.

The virus could only barely replicate in those mice, and half as many of them as in a control group died. When the mice were again exposed to bacteria, however, the ability of the polio to replicate and infect their bodies returned.

The researchers found a similar pattern when the mice were inoculated with a virus from the reoviridae family, which doesn't usually affect humans.

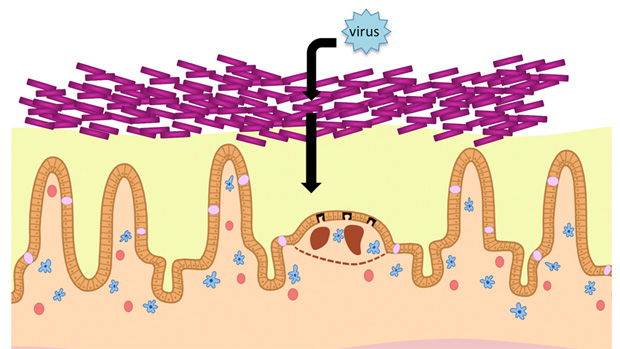

The scientists say the polio used molecules on the bacteria's surface called lipopolysaccharides, which consist of a fat hitched to a carbohydrate, to slip past the body's defences.

'Unexpected'

In the second study, researchers at the University of Chicago looked at mouse mammary tumour virus, a retrovirus that infects baby mice through their mother's milk. Mothers who received antibiotics to kill their intestinal bacteria, or "microbiota," did not pass MMTV to their offspring.

"MMTV has evolved to rely on the interaction with the microbiota to induce an immune evasion pathway," the scientists write.

The results of both papers suggest that the teeming mass of germs in the gut - there are an estimated 100 trillion bacterial cells in the average person, or 10 times the number of body cells - isn't as benign as previously thought, since the bacteria assist some viruses in invading.

Overall, the microbiome - the term for the collection of bacteria living in the body - is still more helpful than harmful. The microbes generally crowd out dangerous, invading germs and also help the immune system to develop.

However, "the studies uncover an unexpected aspect of microbiome contribution to viral infection cycles," Ruslan Medzhitov, an immunologist at Yale University in Connecticut, said in a release accompanying the journal articles. "The work adds to a growing appreciation of the importance of the microbiome."

Both studies are published in Friday's edition of the journal Science.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter