© redOrbit

Scientists have for the first time used a form of cloning to create personalized embryonic stem cells, an important advancement that could impact the study and treatment of diseases such as diabetes, Parkinson's and Alzheimer's.

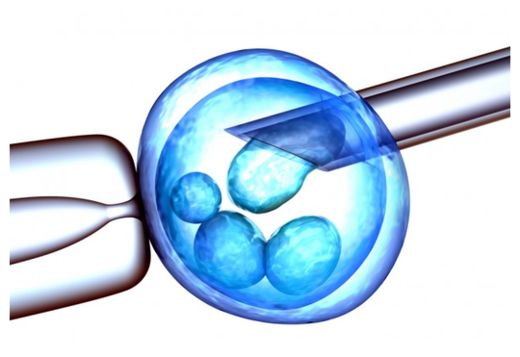

The researchers derived embryonic stem cells from individual patients by adding the nuclei of adult skin cells from patients with type-1 diabetes to unfertilized donor oocytes.

Stem cells are primitive cells that differentiate into the various tissues of the body. Scientists believe stem cells may someday be used in humans to create replacements for diseased or damaged organs.

The idea behind the current research is to take versatile stem cells from early-stage embryos that have been "cloned" to the same DNA as the patient, so that any cells are recognized as friendly by the patient's immune system. By comparison, conventional cloning involves taking an egg and removing its nucleus, which contains the vital DNA code. The core is then replaced with the nucleus of a cell from the donor, and the two parts are fused together using electricity.

"The specialized cells of the adult human body have an insufficient ability to regenerate missing or damaged cells caused by many diseases and injuries," said study leader Dr. Dieter Egli at The New York Stem Cell Foundation (NYSCF) Laboratory in New York City.

"But if we can reprogram cells to a pluripotent state, they can give rise to the very cell types affected by disease, providing great potential to effectively treat and even cure these diseases."

Pluripotent stem cells can give rise to any fetal or adult cell type. However, alone they cannot develop into a fetal or adult animal because they lack the potential to contribute to extra-embryonic tissue, such as the placenta.

"In this three-year study, we successfully reprogrammed skin cells to the pluripotent state. Our hope is that we can eventually overcome the remaining hurdles and use patient-specific stem cells to treat and cure people who have diabetes and other diseases," he said.

But the scientists were able to demonstrate for the first time that the transfer of the nucleus from an adult skin cell of a patient into an oocyte, without removing the oocyte nucleus, results in reprogramming of the adult nucleus to the pluripotent state. Embryonic stem cell lines were then derived from the oocyte containing the patient's genetic material.

But since these pluripotent stem cells also have a copy of the chromosome from the oocyte, they contain an abnormal number of chromosomes and are not ready for therapeutic use.

Future work will focus on understanding the role of the oocyte chromosome so that patient- specific stem cells can be made that contain only the patient's DNA, the researchers said.

In the current study, skin cells from patients with type-1 diabetes and those from a control group were reprogrammed, allowing the derivation of pluripotent stem cells that could potentially be used to create beta cells that produce insulin.

Patients with type 1 diabetes lack insulin-producing beta cells, resulting in insulin deficiency and high blood sugar levels. Producing beta cells from stem cells for transplantation holds promise for the treatment and potential cure of type-1 diabetes.

The study raises the possibility of using somatic cell reprogramming to create banks of stem cells that could be used for a wide range of patients, said Dr. Robin Goland, co-director of the Naomi Berrie Diabetes Center and another collaborator on the work.

However, the researchers caution that further work is necessary before these cells can be used in cell-replacement medicine.

"This research brings us an important step closer to creating new healthy cells for patients to replace their cells that are damaged or lost through injury," said NYSCF CEO Susan L. Solomon.

"This is an important step toward generating stem cells for disease modeling and drug discovery, as well as for ultimately creating patient-specific cell-replacement therapies for people with diabetes or other degenerative diseases or injuries," said Dr. Rudolph Leibel, co-director of Columbia's Naomi Berrie Diabetes Center and a collaborator in the study.

The study was published Wednesday in the journal

Nature.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter