© Minyanville

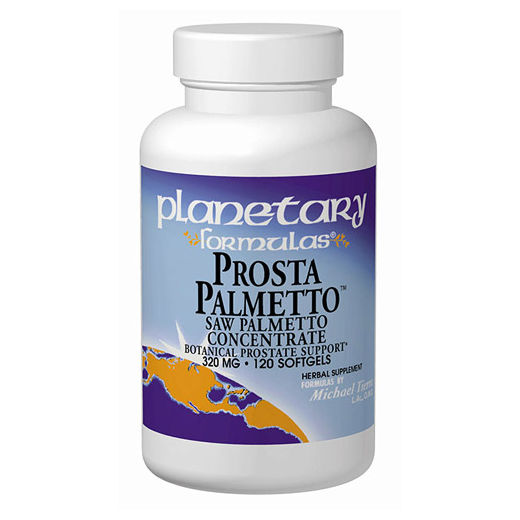

A new study published yesterday in the

Journal of the American Medical Association, has debunked claims that saw palmetto is an effective treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia, or BPH.

According to Science Daily, "Many older U.S. men take saw palmetto extract in an attempt to reduce bothersome symptoms of a swollen prostate, including frequent urination and a sense of urgency." The journal goes on to explain that saw palmetto's "use in Europe is even more widespread because doctors often recommend saw palmetto over more traditional drug treatments."

BPH can be treated with Merck's Proscar or GlaxoSmithKline's Avodart. However, Dr. Gerald Andriole and his team found that the supplement provides exactly zero benefit for sufferers of BPH.

"Now we know that even very high doses of saw palmetto make absolutely no difference,"

Andriole said. "Men should not spend their money on this herbal supplement as a way to reduce symptoms of enlarged prostate because it clearly does not work any better than a sugar pill."

Dr. Ruth Kava of the

American Council on Science and Health is less than surprised.

"Just as beta-carotene's supposedly beneficial impact on lung cancer was disproven, saw palmetto doesn't pass muster when it comes to treating BPH symptoms," she points out in the council's newsletter. "Just because these things are 'natural,' doesn't mean they actually work."

Dr. Josh Bloom, also of ACSH, says that "this is just another example of a so-called supplement that ends up being useless when held up to the scrutiny of clinical trials. Soy, flax seed oil, valerian, and echinacea have gone down the tubes recently as well."

The supplement industry has been a tremendous moneymaker for many years.

In a 2010

article in Forbes, titled "Snake Oil in Your Snacks," Thomas Pirko, president of Bevmark consulting, whose clients include Coke, Kraft, and Nestlé, told reporters Matthew Herper and Rebecca Ruiz, "We're going through a revolution in food. It's a whole new consciousness -- every product has to be adding to your health or preventing you from getting sick."

If you find the perfect additive, he said, "you get rich."

But Dr. Elizabeth Whelan, founder and president of ACSH, explained to us last October that the makers of products like POM have been exploiting loopholes available to the health food industry that the mainstream food industry does not enjoy.

"What's we're seeing here is really a double standard," she said. "They are basically immune from FDA action because of the special protection given to supplements [and functional foods], which exist in a special non-food, non-drug space. If you can get people to view food as medicine, you've got a willing, vulnerable audience. Did you ever wonder why so much of the nutritional supplement industry is based in Utah? You can trace much of it back to Senator Orrin Hatch."

Huh? Orrin Hatch? Wha?

"He is by far our greatest advocate", said Loren Israelson, executive director of the Utah Natural Products Alliance (now called the United Natural Products Alliance), which is an association of dietary supplement and functional food companies that form an alliance to challenge the FDA's

'aggressive and inappropriate enforcement actions'... "No one rises to the issue the way Senator Hatch does. He's a true believer in natural health."

Hatch is apparently also a true believer in helping those who have helped him. In 2003, the

Los Angeles Times exposed the fact that "that the supplements industry has not only showered the senator with campaign money but also paid almost

$2 million in lobbying fees to firms that employed his son Scott."

From 1998 to 2001,

Scott Hatch worked for Parry and Romani Associates, a lobbying firm run by Tom Parry, a former senior aide to Senator Hatch, with clients in the supplements industry. More than $1 million came from companies seeking help in blocking increased regulation of ephedra, a natural amphetamine-like stimulant, which had been named as a possible cause in 80 deaths nationwide.

The FDA backed down after Hatch, along with Iowa Senator Tom Harkin (who believes bee pollen cured his allergies) protested the "incomplete nature of some of the incident reports, which came from users, doctors and other sources."

Strangely enough, the kind of information Hatch and Harkin were insisting on was exactly the type of detailed data the two legislators exempted supplement makers from collecting -- the results of premarket tests and clinical trials required of prescription medications -- when they introduced the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) in 1994. DSHEA was signed into law by President Bill Clinton, and eliminated any power the FDA had to review, test, or regulate dietary supplements, as long as the now-familiar disclaimer was displayed on the packaging: "This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease."

(At the time, Hatch happened to own nearly 72,000 shares of Pharmics, Inc., a Utah company that sold prenatal vitamins and vitamin C additives, and whose president, Walter J. Plumb III, is Hatch's former law partner.)

Fresh off the ephedra victory, Hatch's son Scott opened his own lobbying firm, Walker, Martin & Hatch, representing, among others, clients in the supplements sector, some of whom followed him from Parry and Romani.

Senator Hatch told the

Los Angeles Times that he saw "

no conflict of interest in championing issues that benefit his son's clients."

"I would have no qualms talking to Scott," about his clients, Hatch said. "I wouldn't do anything for him that wasn't right.

"Right" in the eyes of the law is sometimes a bit different from "right" in ethical terms.

It turns out that Jack Martin, the "Martin" in Walker, Martin & Hatch, was a staff aide to Senator Hatch for six years, and the "Walker" on the firm's shingle is H. Laird Walker, a close associate -- and generous campaign donor -- of Senator Hatch.

"This is typical revolving door influence peddling that major businesses exploit to the nth degree," Craig Holman, legislative representative for Public Citizen, a Washington, D.C. policy organization which champions citizen's interests, told me in a telephone interview. "The best way to protect a business's own interest is to employ former staff members of a politician who has direct influence over that industry. There's really no more effective way to get a senator on your side than to abuse the revolving door."

Though saw palmetto seems not to work, the supplement industry is already doing its best to

cast doubt on Andriole, et al's findings.

However, saw palmetto does have very tangible benefits for some:

saw palmetto berry pickers, who else?

The journal goes on to explain that saw palmetto's "use in Europe is even more widespread because doctors often recommend saw palmetto over more traditional drug treatments."

(Traditional drug treatments? Don't you mean pharmaceutical drug treatments or surgery?)

And therein lies the problem. Its cutting into the profits of BigPharma, so they do their best to debunk.

It may be true, it may not.

But I am less inclined to believe JAMA's opinion because of their obvious bias.

I feel the same way about this article.

So, why do so many people take it?

Oh yes, of course! Because they are weak minded and easy to manipulate.

Please!