The unmanned Russian cargo ship Progress 44 crashed just after its Aug. 24 launch to deliver 2.9 tons of supplies to the orbiting lab. The failure was caused by a problem with the Progress' Soyuz rocket, which is similar to the one Russia uses to launch its crew-carrying vehicle, which is also called Soyuz, to the station.

Currently, six astronauts reside on the space station. But three of them are due to return to Earth next month, and the rest are scheduled to come back in mid-November. If the rocket anomaly isn't identified and fixed soon, a fresh crew won't be able to get to the station before the last three astronauts depart.

Unmanned for the first time in a decade?

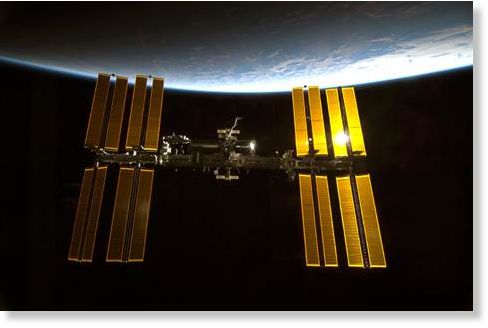

That situation would leave the $100 billion orbiting lab unmanned for the first time since 2001. Still, it wouldn't be a disaster, according to NASA officials.

"We know how to do this," NASA's space station program manager Mike Suffredini told reporters Monday. "Assuming the systems keep operating, like I've said, we can command the vehicle from the ground and operate it fine, and remain on orbit indefinitely."

NASA would, of course, prefer to keep some crew aboard the orbiting lab, Suffredini added. Leaving the station unmanned would cut back significantly on the scientific research being done 220 miles above the Earth.

But the timing just might not work out. Two Soyuz spacecraft are currently docked to the station to take its six astronauts home. The vehicles are only rated to spend about 200 days in space, so they'll have to depart soon.

Light at the landing site

Lighting conditions at the Soyuz's Kazakhstan landing site are also an issue. NASA and the Russian space agency mandate that landings must occur at least one hour after dawn and one hour before dusk, to faciliate better search-and-rescue operations should any be required.

The lighting window closes for a month on Sept. 19 for the first crew and around Nov. 19 for the second. Waiting for a new window to open would stretch the Soyuz beyond their 200-day ratings in both cases, Suffredini said.

So all six astronauts on the space station will almost certainly have left the orbiting lab by mid-November. Russian engineers are working hard to give crewed Soyuz launches the best chance to meet that deadline; the next one is slated to blast off Sept. 21, but that's almost certainly not going to happen, Suffredini said.

Russia has formed a commission to determine the cause of the Progress crash, and to figure out how to fix it. But NASA says it won't rush anything, as astronaut safety is its chief priority.

"We'll just see how it plays out," Suffredini said.

The Space Shuttle has gone, next the station. And you can bet that Richard Branson will never get his ship to go into space more than once or twice before something happens to that! What don’t they want anyone to see out there? Comets, asteroids, satellites or other things?