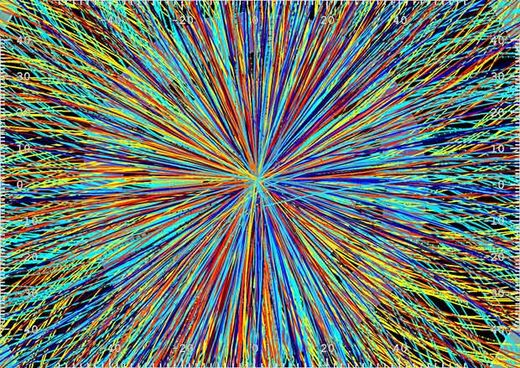

Bursts of heat hundreds of thousands of times more intense than the sun are generated as lead ions collide in conditions colder than outer space, releasing exotic new particles.

The reaction creates a kaleidoscope of colours as the energy of each particle is detected by recording equipment at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN.

The base near Geneva, Switzerland, is where scientists are searching for the Higgs boson particle, an as-yet undetected form of matter which scientists hope will reveal how atoms are made up.

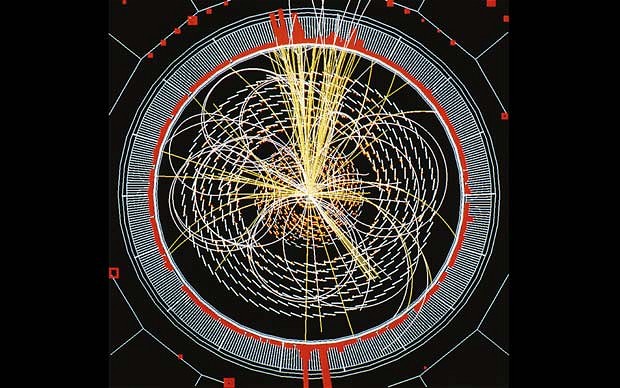

Another image released by CERN predicts how the Higgs boson, known as the "God" particle, might look to scientists as it decays a fraction of a second after it is created in the LHC, a 16 mile-long ring through which atoms are fired at one another.

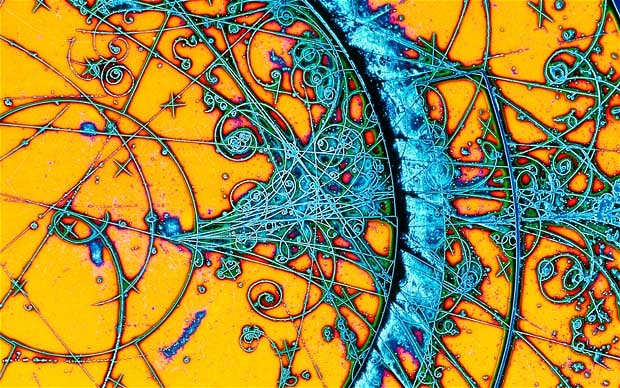

A third picture shows trails of bubbles left behind when particles smaller than atoms travel through liquid hydrogen, taking a variety of curved paths due to the strong magnetic field around them.

Particle physicist and CERN spokesperson Christine Sutton said: "When two lead ions collide basic particles like pions - one of the basic particles that make up atoms - are expelled.

"Sub-atomic particles such as these include the basic building blocks of atoms and are common in the universe.

"So by studying these we can learn more about what the universe is made from and perhaps one day how it all began."

Last week LHC physicists announced that they should be able to determine within 18 months whether or not the Higgs boson exists.

Although the particle itself still eludes them, experts continue to narrow down the areas in which it might be found, meaning a result may not be far off.

Rolf-Dieter Heuer, director general of the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (Cern), told reporters: "I would say we can settle the question of the Higgs boson, the Shakespearean question 'to be or not to be' at the end of next year."

...proving an ideology.

The god "particle" does sound exciting though, doesn't it?

Ha!