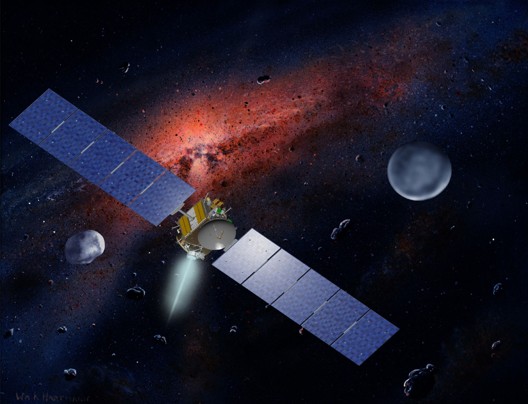

© AP Photo/NASAAn artist's concept showing Dawn spacecraft with Ceres and Vesta.

After spiraling outward from Earth for four years, NASA's

Dawn probe is set to slide into orbit around the potato-shaped asteroid Vesta early Saturday for a year-long look at an ancient "mini moon."

Three hundred fifty miles wide and heavily cratered, Vesta formed some 4.5 billion years ago, when the sun was still young. By probing its secrets, scientists hope to catch a glimpse of how the planets, including Earth, formed out of a swirling disk of gas and dust.

"We are exploring backward in time as far as we can," said lead mission investigator Christopher Russell of the University of California at Los Angeles. "There's going to be a whole bunch of surprises."

Unlike most smaller asteroids - thought to be nearly uniform lumps of rock - Vesta is a "mini moon," Russell said, made up of three layers: an iron core, a rocky mantle and an upper crust. Early in Vesta's existence, Russell said, lava welled up from its interior and cooled to form a crust of volcanic rock.

"Vesta is unique among the large asteroids," said Richard Binzel, professor of planetary sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "It's the only one covered with a volcanic surface."

Despite observations from the Hubble Space Telescope, many mysteries of Vesta's origin and composition remain, including why the asteroid's surface is so dark.

Its solar wings spread wide,

Dawn should begin orbiting Vesta around 1 a.m. Saturday. Vesta's slight gravity - just 2 percent that of Earth's - will gently capture the probe, which is closing in on the asteroid at just 100 miles per hour.

"We've had a smooth flight," Russell said of the $466 million mission that launched a year behind schedule.

For the next year,

Dawn will slowly spiral toward Vesta's surface, coming within 120 miles. As cameras snap photos, other instruments will probe the asteroid's makeup.

There may be hills, mountains and even extinct volcanoes on Vesta's surface, Russell said.

In 1997, images from the Hubble Space Telescope revealed an eight-mile-deep crater on Vesta's southern hemisphere. The collision that carved the crater sent a huge plume of rock and dust hurtling through the solar system. Some of that material landed on Earth as meteorites, Russell said.

In fact, scientists estimate that some 20 percent of all meteorites came from Vesta, which was discovered by a German astronomer in 1806.

The second-most-massive asteroid in the solar system, Vesta circles the sun in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Had Jupiter's massive gravity not interfered, the millions of space rocks in the asteroid belt might have coalesced into another planet, scientists say.

Unlike rocket-powered craft sent to Mars, Jupiter and other planets,

Dawn is driven by a weak-but-steady ion engine. Powered by solar panels,

Dawn's engines zap a gas, xenon, with an electrical charge. As the charged gas shoots out a nozzle, it imparts a gentle push - equivalent to the weight of a sheet of paper sitting on your hand, said Mark Rayman, chief engineer for

Dawn at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

But what

Dawn lacks in power, it makes up in stamina. Its engines have been thrusting for some 1,000 days, steadily adding speed.

Sipping just milligrams of xenon a day, the super-efficient engines leave

Dawn with enough fuel to push itself toward a second asteroid. If all goes well, next summer the 65-foot-wide craft will depart Vesta and head toward the largest asteroid in the solar system, Ceres, with arrival scheduled for 2015. Ceres intrigues scientists because it apparently holds a huge reservoir of water, Russell said.

If successful,

Dawn's double-destination mission will mark the first time a spacecraft has orbited two bodies in the solar system.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter