OF THE

TIMES

Today as never before we need to comprehend the course, logic, and path of the process of history. Every day we need to make decisions that will affect future generations. It has become obvious that no single nation, confession, social class or even civilization can solve these problems on its own. We increasingly have to listen to one another: Europe and Asia, Christians and Muslims, White and Black peoples, citizens of modern democratic states and places where traditional society survives. The key is to understand one another correctly, avoid hasty conclusions, and acquire the true spirit of tolerance and respect toward those with different value systems, habits, and norms.

I'm kind of fond of menthol - clears out the lungs..... I don't think it ought be banned. Menthol chemically is sort of like "glass" the body can...

Maybe substitute them with Menthol Grape Drank...

Seth says that, " I've never even been in a physical fight of any kind in my life " Seth doesn't get out much, so I will take what he writes with...

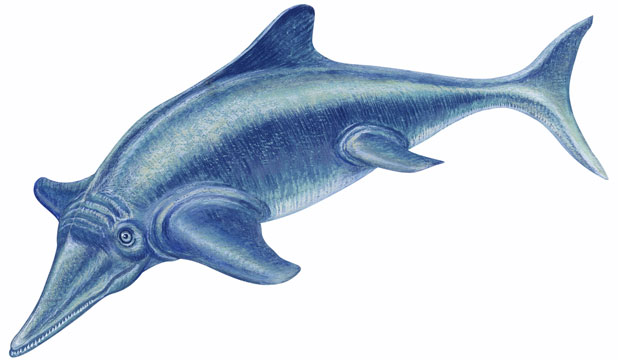

Key words in this article: possible, theorized, circumstantial, depicted, computer simulations, plausible... Main takeaway from this article: "...

" The White House argued that outlawing menthol cigarettes would help "people of color" improve health outcomes. " No government should have that...

To submit an article for publication, see our Submission Guidelines

Reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views of the volunteers, editors, and directors of SOTT.net or the Quantum Future Group.

Some icons on this site were created by: Afterglow, Aha-Soft, AntialiasFactory, artdesigner.lv, Artura, DailyOverview, Everaldo, GraphicsFuel, IconFactory, Iconka, IconShock, Icons-Land, i-love-icons, KDE-look.org, Klukeart, mugenb16, Map Icons Collection, PetshopBoxStudio, VisualPharm, wbeiruti, WebIconset

Powered by PikaJS 🐁 and In·Site

Original content © 2002-2024 by Sott.net/Signs of the Times. See: FAIR USE NOTICE

It is so scary to see such large vicious predatory beast..........