While "flesh-eating infections" caused by the group A streptococcus (

Streptococcus pyogenes)

may grab more headlines today, one hundred and fifty years ago, the best known and most dreaded form of streptococcal infection was

scarlet fever. Simply hearing the name of this disease, and knowing that it was present in the community, was enough to strike fear into the hearts of those living in Victorian-era United States and Europe. This disease, even when not deadly, caused large amounts of suffering to those infected. In the worst cases, all of a family's children were killed in a matter of a week or two. Indeed, up until early in the 20th century, scarlet fever was a common condition among children. The disease was so common that it was a central part of the popular children's tale,

The Velveteen Rabbit, written by Margery Williams in 1922.

Luckily, scarlet fever is much more uncommon today in developed countries than it was when Williams' story was written, despite the fact that we still lack a vaccine for S. pyogenes. Is it gone for good, or is the

current outbreak in Hong Kong and mainland China a harbinger of things to come?

First, what are the symptoms of scarlet fever? Most often, this manifestation occurs during or following strep pharyngitis ("strep throat"). Rarely, scarlet fever occurs after the skin infection, impetigo. Children with scarlet fever develop chills, body aches, loss of appetite, nausea, and vomiting; these are symptoms may occur at the same time as or shortly following the onset of pharyngitis. When the rash emerges, it typically seems like an itchy sunburn with tiny bumps. After first becoming visible on the neck and face, it spreads to the chest and back, later spreading to the arms and the remainder of the body. Though initially consisting of separate bumps, these bumps tend to merge together, giving the entire torso a red appearance. Generally, the rash beings to fade by about the sixth day; and similarly to sunburn, the skin may peel afterwards. The tongue, typically very red and bumpy ("strawberry tongue") may also peel.

Scarlet fever is nothing new to humanity, though the earliest case definition of scarlet fever is a matter of contention. Some researchers attest that descriptions of disease which match scarlet fever date back almost 2,500 years, to Hippocrates. Others believe the first conclusive diagnosis is found in the tenth century writings of Rhazes, who also worked to distinguish measles and smallpox as separate diseases. It is generally agreed upon that the first sufficiently detailed paper identifying scarlet fever as a disease distinct from other rashes appears in 1553. In that paper, the Italian physician Giovanni Ingrassia describes the disease and refers to it as "rossalia." The term "febris scarlatina" appears in a 1676 publication by the British physician, Thomas Sydenham.

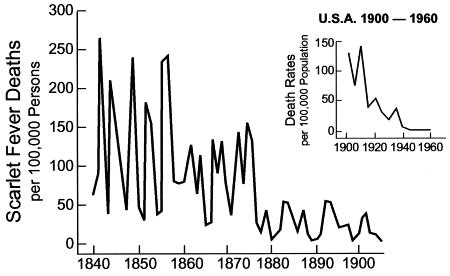

Historical data suggest at least three epidemiologic phases for scarlet fever. In the first, which appears to have begun in ancient times and lasted until the late eighteenth century, scarlet fever was either endemic (always present at a low level) or occurred in relatively benign outbreaks separated by long intervals. In the second phase (~1825-1885), scarlet fever suddenly began to recur in cyclic and often highly fatal urban epidemics. In the third phase (~1885 to the present), scarlet fever began to manifest as a milder disease in developed countries, with fatalities becoming quite rare by the middle of the 20th century. In both England and the United States, mortality from scarlet fever decreased beginning in the mid-1880s. By the middle of the twentieth century, the mortality rate from scarlet fever again fell to around 1%.

Fig. 1. Boston 1840-1940. Severe streptococcal infections in historical perspective. Depicted in the insert are the recorded deaths in the United States from 1900 to 1960. From Krause RM, citation below.

During Sydenham's life (1624-1689) and for more than a century afterwards, scarlet fever was considered by both parents and physicians to be a relatively mild childhood disease. Although several European cities experienced fatal epidemics of the disease, these epidemics were often short-lived, and it does not appear they were widespread.

In the early nineteenth century, the clinical presentation of the disease appears to have changed for the worse. Lethal epidemics were seen in Tours, France, in 1824; in Dublin, Ireland, in 1831; and in Augusta, Georgia, during 1832-33. Similarly, in Great Britain, the fatality rate from scarlet fever increased from between 1 and 2 % to more than 15% in 1834.

From 1840 until 1883, scarlet fever became one of the most common infectious childhood disease to cause death in most of the major metropolitan centers of Europe and the United States, with case fatality rates that reached or exceeded 30% in some areas--eclipsing even measles, diptheria, and pertussis.

Scarlet fever pandemics of this and other eras also had a profound effect on history, in addition to providing a plot device for a beloved children's story. Charles Darwin lost two of his children to scarlet fever. The first, his beloved daughter Annie, died at the age of 10 in 1851 (two sisters, also infected, recovered from this bout). In July 1858, Darwin also lost his 18-month-old son, Charles Waring, to scarlet fever. It is believed that a bout of scarlet fever at the age of 19 months caused Helen Keller to lose her senses of vision and hearing. Scarlet fever also led to the founding of The Rockefeller University by the world's first billionaire and the founder of Standard Oil, John D. Rockefeller, whose 3-year-old grandson died of scarlet fever. Rockefeller remains a leader in biomedical research today, including research investigating various aspects of the biology of the group

A streptococcus.

Why did scarlet fever, once a scourge of childhood, end up as a relatively rare infection in developed countries? While some of this can be attributed to antibiotics (particularly from the 1950s on), both the incidence of scarlet fever and mortality from the illness started to decline well before the antibiotic era (seen on the graph above)--a phenomenon that may be attributable to the emergence of novel strains of

S. pyogenes in the population which were less likely to cause scarlet fever, but more likely to spread in the population. (A similar strain replacement may have occurred in the late 1970s/early 1980s, leading to the increase in the aforementioned "flesh eating" strains of strep). Other biological factors such as herd immunity to epidemic strains, as well as social factors including decreased crowding, improved hygiene, and even milk pasteurization (milk was responsible for several large group A strep outbreaks) also probably contributed to this decrease.

Scarlet fever still remains a threat today, particularly in developing countries, but nowhere today is it as severe a disease as it was during that frightening time in the middle of the nineteenth century. However, the

current outbreak in China shows how quickly this situation can change, as they've seen a quadrupling in the number of cases in 2011 compared to previous years and several fatalities. News stories have

suggested this is some kind of "mutant" strain and has increased resistance to antibiotics, though I haven't seen much elaboration on either of those claims. (

This story touts "the new strain has about 60 percent resistance to antibiotics used to treat it, compared with 10 percent to 30 percent in previous strains," which doesn't make much sense as written--maybe resistance to 60% of the antibiotics tested...?) Though still of relatively low mortality compared to Victorian era, the resurgence of this disease, and the potential for the emergence of a new strain shows how quickly this disease can make a comeback. Additionally, at least one article notes

a simultaneous outbreak of chickenpox--and strep plus

varicella zoster (the chickenpox virus)

can be a nasty combination.

I also wonder if the current outbreak is really caused by a new strain as suggested, or by one that has been

percolating throughout Asia for awhile and only recently hit the big time. I guess time -- and hopefully sequencing data -- will tell.

Further reading:Katz SL, Morens DM. Severe streptococcal infections in historical perspective.

Clin Infect Dis 1992;14:298-307.

Link.

Krause RM. Evolving microbes and re-emerging streptococcal disease.

Clin Lab Med. 2002 Dec;22(4):835-48.

Link.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter