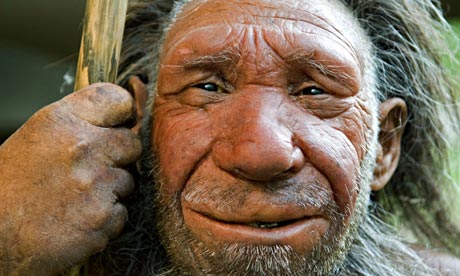

I am at a conference in Dubai on science, religion and modernity, and the best question to come up was "should we clone Neanderthals?" Let's assume the kind of technical progress which would make this look like a possibly ethical thing to do: the failure rate with mammalian cloning has been so high that it really would be rather dodgy to inflict the process on a human being. But for the sake of argument assume a reliable technology and a sufficiency of DNA to work with.

Of course, the first difficulty from the strictly utilitarian point of view is that we don't know what the consequences would be. Neanderthal brains were physically different from ours and we have no idea how that impacted their consciousness. We assume they had speech, but this is obviously something that does not fossilise. So it's hard to judge the consequences inflicted on a sentient being when we have no clear idea of what kind of sentience is involved.

So a straightforward calculation of the likely consequences can't be done in the way that it can at least be attempted in bioethical questions as they affect homo sapiens. That doesn't mean that religion can provide answers, either. I haven't asked a Roman Catholic but assume that they would apply the same kind of precautionary principle as is applied in the case of abortion: that something which might be a human being should always be given the benefit of the doubt. But other religions, and other forms of Christianity, are not opposed to human cloning. They might not be opposed to cloning Neanderthals.

So let's not set it up as a science v religion argument. There will be ethical disagreement, but this will lie between believers as much as between unbelievers.

Does it make a difference that this would be an experiment? It's science, which means that we discover things by trial and error. These trials are carefully constructed to ensure that the errors are as instructive as possible, but the outcome can't be known in advance. It's not easy to see how one could be certain of having a complete and viable sequence of Neanderthal DNA when there is nothing to compare it with and only the broad assumption that if the specimen from which it was extracted made it to adulthood it was reasonably healthy.

OK: let's try from another angle. Surely the final ethical test of this is that the cloned Neanderthal would be happy to have been born. Looked at from this angle, it is immediately obvious that it would be wrong to clone a Neanderthal. No one would want to be the only member of their species. The minimum ethical thing to do would be to clone 20 or 30. We would not be bringing back an individual, but a species, for which we would then become responsible.

What religion would these creatures have? We know that Neanderthals had rituals, and presumably beliefs, around death. These are lost forever. Should they be replaced? If Neanderthals are enough like us to bury their dead, they will make mythologies with or without our help. What should those be? If two separate countries or cultures cloned two different Neanderthal cultures, would each regard the other as heretics?

All this presupposes that they can be taught contemporary languages. Again, the choice here is obviously arbitrary but not terribly important, though I admit to a sneaking desire to have them all taught Latin or ancient Greek. But at the same time it is reasonably certain that they would develop and bend the language they were given to map onto their rather different cognitive faculties.

Whatever happened, it would be entirely fascinating to observe. There would be other advantages. The revival of a species from 25,000 years ago would be a wonderful window onto our own nature; it would provide a stunning and - if evidence had anything to do with it - irrefutable argument against creationists. It would enrich our understanding of consciousness, of biodiversity, and it should also be wonderful for the Neanderthals. Who would not rather be alive and healthy than dead?

Nonetheless, there are two reasons why it should never be attempted. The first is feminist. Cloning does not stop in a petri dish. There must be surrogate mothers, and they would be just as much the subjects of these experiments as the Neanderthal embryos. Given the enormously complex interplay between a mother's immune system and a human foetus, it's hard to imagine things would go better when another species was involved.

The second is also concerned with the differences that evolution brings about: a Neanderthal of 25,000 years ago would have essentially no immunity to any of the diseases that have evolved since then. All of us now alive are descended from the survivors of centuries of epidemics. They flourished, in turn, because of human settlement patterns. We have no right to bring anyone else into the mess we have made.

Heck yea let's clone 30-40 and see what happens.Maybe given time they will take back what they lost so many years ago.Besides think of what we would learn from them.We might not like what we see tho.