Scientists used very high-resolution scanning to study the skulls of two of the earliest known mammal species.

Comparing the shape of their brain cases to those of slightly earlier animals, or "pre-mammals", revealed that the first brain areas to over-develop were those associated with the sense of smell.

The findings are published in Science.

An improved sense of smell may have allowed our tiny, furry ancestors to hunt at night.

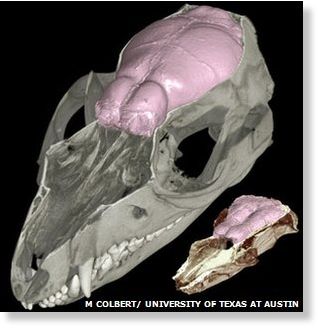

The researchers were able to create 3D images of prehistoric animals' brains using the latest computed tomography, or CT, scanning methods.

"Before CT, one had to break open a fossil to get to the internal anatomy," explained Professor Timothy Rowe from the University of Texas at Austin, one of the researchers involved in the study.

"[This technique] is non-destructive, so we can measure internal anatomy in ways that were never before possible."

Evolution timeline

Mammals, and humans in particular, have the largest brains in the animal kingdom, relative to the size of their bodies. So the scientists wanted to work out why mammal brains evolved to become so very large and complex.

To do this, they studied the earliest known mammals - the tiny fossilised skulls of 190-million-year-old Morganucodon oehleri and Hadrocodium wui, both of which were discovered in China.

By comparing these skulls to those of more primitive animals, and to living mammals, they were able to build a sequence of events in the evolution of mammal brains.

The team found that, in early mammals, the brain regions associated with smell were much larger than in more primitive or "pre-mammal" ancestors.

"Based on what we know from living species, interpreting the [brain scans] of these 200 million year old fossils was pretty straight forward," said Professor Rowe.

He and his colleagues concluded that smell "drove most of the early expansion of the brain in these first 'proto-mammals' and in the last common ancestor of living mammal species".

Dr R Glenn Northcutt from the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved in the research, wrote an accompanying article in the same issue of Science describing its significance.

He said that the study provided "the first solid evidence of the stages in mammalian brain evolution".

The researchers think that, 200 million years ago, mammals probably used their keen sense of smell to hunt at night, which meant that they could avoid competing for food resources with dinosaurs that shared their habitats.

"This would allow them to take advantage of nocturnal food sources like some of the insects and other arthropods that are active at night," Professor Rowe suggested.

He told BBC Nature that he was surprised to learn that smell was so important in mammal evolution.

"Most of the fossil record consists of just teeth and broken jaws, so most of the speculation was about innovations in feeding and hearing, which is tied to the jaw," he said.

"Until now, [smell] was not really on the radar screens of most palaeontologists."

Dr Zhexi Luo from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, who was also involved in the study said: "Our mammal ancestors didn't develop that larger brain for contemplation, but for the sense of smell and touch.

"But thanks to these evolutionary advancements, which gave mammals a head start toward developing a large brain, humans some 190 million years later can ponder these very questions of natural history and evolution."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter