Oxford- In the first major archaeological exhibition in the new temporary exhibition galleries, the

Ashmolean Museum showcases over five hundred treasures made of gold, silver and bronze, recently found in the royal burial tombs and the palace of Aegae, the ancient capital of Macedon. These extraordinary new discoveries are on display for the first time outside Greece. They re-write the history of early Greece and tell the story of the royal court and the kings and queens who governed Macedon, from the descendents of Heracles to the ruling dynasty of Alexander the Great. On view from April 7 through August 29, 2011.

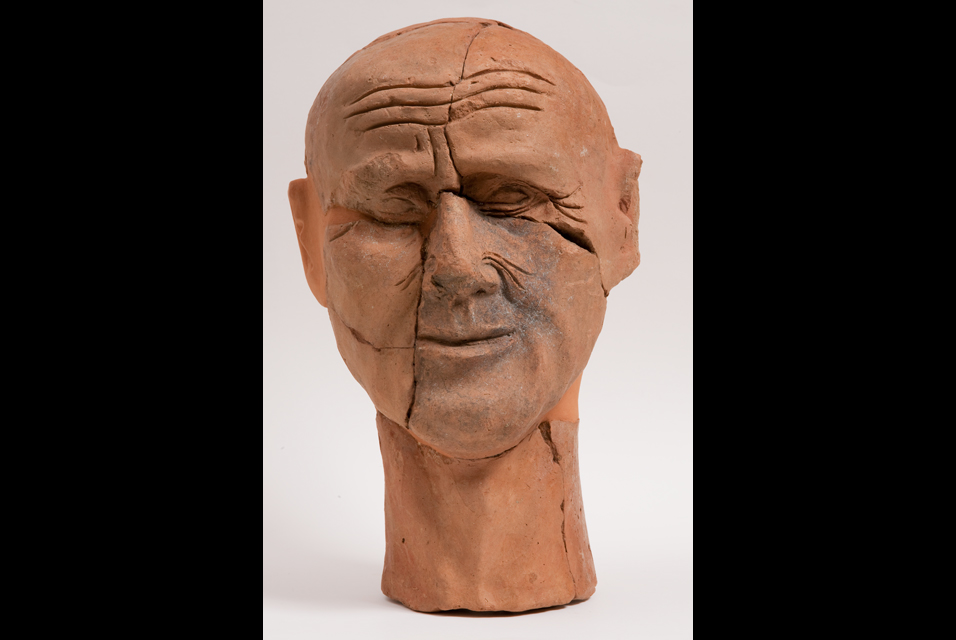

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Archaeological Receipts Fund.Clay bust.

"This exhibition is a very important cultural event for Greece. From the astounding finds made by the late Professor Manolis Andronikos in the '70s to the recent discoveries of the past twenty years, this is groundbreaking work that tells the story of life in the ancient kingdom of Macedon, northern Greece. The artistry, skill and foresight with which these objects were made represent a truly sophisticated dynasty about whom there is much more to learn," Dr Angeliki Kottaridi, Director of the 17th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities.

The royal city of Aegae - modern-day Vergina - was the first capital of Macedon and the seat of power of the Temenid kings, named after Temenus, a descendent of Heracles. They ruled from the mid-7th to the 4th century BC, and gave to Greece two of its most famous heroes, King Philip II (382-336 BC) and his son Alexander the Great (356-323 BC). Aegae remained relatively unknown until 30 years ago when excavations uncovered the unlooted tombs of Philip II and his grandson Alexander IV. Recent work at the site has continued to unearth a startling wealth of objects - from beautifully intricate gold jewellery, silverware and pottery, to sculpture, mosaic floors and architectural remains.

The exhibition is an international first with presentations directly connected with central figures of the Temenid court. In the first of three major themes that brings this ancient society to life is the world of the king and his companions at war and hunting; the king as ruler and high-priest, and the royal funeral. In this section, arms and armour, golden wreaths, life-sized marble sculpture, and painted battle-scenes illustrate the lives of Macedon's most famous kings, among them Philip II and Alexander IV, father and son of Alexander the Great respectively.

The majority of the finds come from the tombs of the royal women, and the exhibition's next section shows their important role at the court. Jewellery, fashion, and objects used for grooming, as well as sacred objects, such as clay heads of divine and demonic figures, underline the leading role of these powerful women as queens, princesses and high-priestesses, offering a vivid portrayal of the female world in the palace from around 1000 to 300 BC. A centrepiece of the show is the assemblage of five women: four dating to the Early Iron Age (1000-700 BC) and one, the 'Lady of Aegae', to around 500 BC. The 'Lady of Aegae', a queen and high-priestess, was found in an undisturbed tomb, bedecked with funerary goods and dressed, head-to-toe, in spectacular gold jewellery which had been sewn into her clothes.

Life in the palace - its architecture and the symposion (banquet) - is the exhibition's concluding theme.

Silverware, ceramics, and architectural fragments from the palace itself give a tantalising glimpse of life in the royal capital of this ancient kingdom. The gallery highlights the development of the 'symposion' - a key expression of the contemporary social and political world, and the rich architecture of the palace built in the reign of Philip II.

'The Macedonians lived under the same political system uninterruptedly for some five hundred years. Nowadays we admire the ancient Greeks for their invention of democracy, but even among the Athenians it lasted much less long. Macedon's system was monarchy, the most stable form of government in Greek history. It persisted from about 650 to 167 BC and only stopped because the Romans abolished it.' Robin Lane Fox, Ancient Historian, University of Oxford.

"It is a tremendous honour for the Ashmolean to be the first place where people can see the latest discoveries from Aegae," Dr Christopher Brown, Director, Ashmolean Museum.

is all I can muster....!