Orangutans, the most distant of our great ape relatives, changed less in 15 million years than our species has in 200,000. And yet orangutans also have tremendous genetic diversity, an apparent contradiction that has created a strange evolutionary riddle.

The family Hominidae, commonly known as the Great Apes, has four main members: humans, chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans. Humans and chimpanzees are the most closely related species, and then both are more related to gorillas than orangutans, who are all alone on their corner of the family tree. Orangutans are now the latest members of the great ape family to have their genomes sequenced, and they've revealed some surprising details about our evolutionary story.

The most shocking has to be that the orangutan genome hasn't changed in 15 million years. To put that in some perspective, our species didn't even really exist until 200,000 years ago, and even the Homo genus doesn't stretch much further back than 2.4 million years. Chimpanzees don't become distinct from our evolutionary ancestors until about six million years ago, and gorillas don't emerge until about 7 million years ago. Orangutans are, by the standards of the rest of their family, an incredibly ancient species.

The key difference is that the orangutan genome evolved very slowly, without any of the rapid-fire bursts of acceleration that we can find preserved in the genomes of humans or chimps. Researcher Richard K. Wilson explains:

In terms of evolution, the orangutan genome is quite special among great apes in that it has been extraordinarily stable over the past 15 million years. This compares with chimpanzees and humans, both of which have experienced large-scale structural rearrangements of their genome that may have accelerated their evolution.Part of the puzzle seems to be a kind of DNA element known as "Alu". Alus are repetitive stretches of DNA that comprise about 10% of our genome and can account for unexpected mutations that help drive evolution. Humans have about 5,000 of these Alus, chimps have 2,000, but orangutans? Well, as lead researcher Devin Locke explains:

If you are editing a book on your computer, you can highlight a paragraph and copy and paste it, delete it or invert it. Duplications, deletions and inversions of DNA are types of structural variations. When we look at the genomes of humans and chimps, we see an acceleration of structural changes over the course of evolutionary history. But for whatever reason, orangutans did not participate in that acceleration, and that was a surprise.

In the orangutan genome, we found only 250 new Alu copies over a 15 million-year time span. This is the closest thing we have to a smoking gun that may explain the structural stability in the orangutan genome.Still, after 15 million years of genomic slumber, orangutans woke up about 400,000 years ago, diverging into the Sumatra and Borneo species. Intriguingly, modern orangutans - particularly the Sumatran orangutans - have incredibly diverse DNA, which seems counter-intuitive considering their evolutionary history. Locke explains:

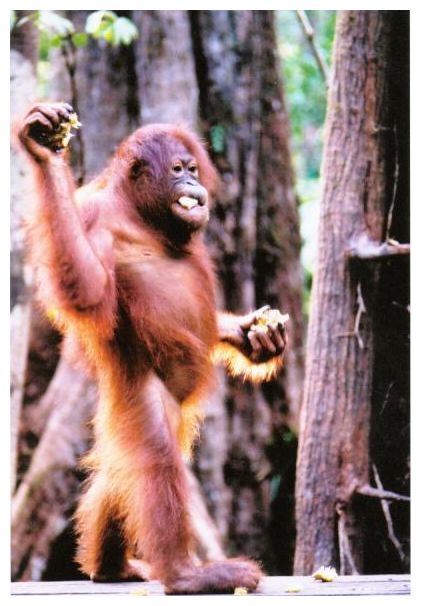

The average orangutan is more diverse - genetically speaking - than the average human. We found deep diversity in both Bornean and Sumatran orangutans, but it's unclear whether this level of diversity can be maintained in light of continued widespread deforestation. It's quite a mystery how Sumatran orangutans obtained this genetic diversity or whether there has been cleansing of diversity in the Borneans. "We can begin to search for answers using the catalog of genetic variation we developed.Of all the Great Apes, orangutans find themselves in the most precarious position. Only 50,000 Bornean and 7,000 Sumatran orangutans still survive in the wild. Continued deforestation of their habitat has placed their long-term survival in serious doubt.

Source

Reader Comments

...evolution taking much, much longer than we have been told or conditioned to believe.

"The most shocking has to be that the orangutan genome hasn't changed in 15 million years. To put that in some perspective, our species didn't even really exist until 200,000 years ago, and even the Homo genus doesn't stretch much further back than 2.4 million years."

what happened God Appollon ? Interestingly enough some marvelous alien species removed a chromosome from that animal category. That gave us the psychopaths more intelligence that proven throughout history we use in a negative way. There was indeed genetic manipulation.