"Eish, it is looking very good for South Africa," the 33-year-old Zulu witch-doctor said after casting her eyes over a seemingly random scattering of animal bones and sea shells during a seance in downtown Johannesburg.

"Look, the trouble is far, far away. No bombs," she added, pointing to a polished and highly decorated knuckle-bone lying apart from the mass of trinkets strewn across the concrete floor in the corner of a dingy bus station.

A weekend newspaper report, vehemently denied by the South African government, of an "80 percent chance" of a terrorist attack during the June 11-July 11 soccer spectacular suggests her confidence is not universally shared.

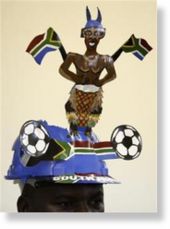

But in Africa, where mysticism and magic play a part in many people's lives, pronouncements from a 'sangoma' such as Nsukwini can carry as much weight as those from governments, especially when it comes to the murky world of security agencies.

In sport, too, sangomas have been a regular but unofficial fixture on the African team sheet, using their ability to commune with the dead to determine a player's fortunes and whether a dose of sympathetic magic and traditional 'muti' potion is in order.

Predicting the outcome of a World Cup is beyond a sangoma's normal remit, although Nkuswini was confident enough to say South Africa would "be strong" despite being a lowly 83rd in the FIFA rankings and 125-1 outsiders according to the bookmakers.

There was more certainty from 78-year-old Nigerian soothsayer John Adatiri, who was able to make a precise call on the outcome despite admitting it was the first time he had analysed a soccer tournament in his 50 years as a mystic.

After a brief but intense stare into a two-sided mirror pulled from an old wash bag in his zinc-roofed hut in Lagos, Adatiri declared: "Nigeria go play quarter final. Brazil go win."

In Ivory Coast, another West African nation with big World Cup hopes, fans have been going to juju priests and a charmed grove near the capital to conjure up some magic on the pitch.

"We are visiting our sacred forest two or three times a week to support the fight," said Gnahouleou Emile, president of the national side's supporters' club.

Bloody Magic

South Africa's sangomas have also done their bit, slaughtering a cow at the new 95,000-seater Soccer City stadium near Johannesburg to bless the pitch and give national side Bafana Bafana (The Boys) a spiritual boost.

However, insiders say traditional beliefs might be on the wane at top domestic clubs due to an influx of non-African coaches who prefer to get their team spirit from the training manual rather than the afterlife.

"All the muti stuff was before my time," said Linda Moreotsene, a soccer reporter at the Sowetan newspaper.

"I can't say I've seen any smoke or herbs being burned in the changing rooms. Many of the top sides have got European coaches now and they don't think much of that sort of thing."

Nevertheless, for many ordinary South Africans, muti -- derived from the Zulu word for 'tree' -- is a potent force and 'muti killings', in which a child or old person is murdered for their body parts, are not unheard of in remote areas.

Muti markets boast a stomach-churning array of decaying animals and aromatic herbs said to cure everything from dodgy knees to marital mishaps -- afflictions common to many of the players now landing on South African soil.

"This one here is for sore legs," said 56-year-old muti merchant Lawrence Mkise, pointing to a sack of powdered orange bark. "And this will make you strong, just like a donkey," he said, with a wink and suggestive thrust of his fist.

"And this one will get your wife back. You rub it on your hand and call out her name. But it is very expensive."

Additional reporting by Tim Cocks in Abidjan and Yinka Ibukun in Lagos

if there was going to be a terrorist attack it would be led by israel.

especially after south Africa kicked beth shin agents out of Oliver Tambo airport for allegedly interrogating Muslims without cause.

but fortunately they are too busy covering their backs with the flotilla thing.

i am in Ssouth Africa and i think it is time this beautiful country shone with abandon.