I had a newspaper route up until I was in the ninth grade, and what I dreaded about the job was going door-to-door collecting subscription fees. The worst part was probably the odors in some of the houses. One house emanated a toxic mixture of Lysol, alcohol, pet dander, and cigarette smoke. These people inevitably were out of cash, so I had to return again and again until I finally was able to negotiate payment -- sometimes months overdue.

But maybe the smell was prejudicing my judgment. Lots of people couldn't pay me right away. Why should I only hate the ones with drinking/pet/smoking/air freshener problems? Other than the fact that they had all those problems, they weren't any better or worse than anyone else (aside from the nice old ladies who baked me cookies I could smell a half-block away).

Hmm... come to think of it, there's a lot a smell can tell you about a person. Are they overperfumed, undermouthwashed, sweaty, smoky, or infused with motor oil? Different scents clearly have different meanings.

But some smells are too subtle to be detected. You might not be able to discern your wife's perfume by the end of the day, although traces are still present. What if someone else was wearing her perfume, still at levels you don't consciously notice? Would that affect your impression of them?

We know from studies on subliminal images and sounds that even when we're not conscious of these things, they can affect our judgments and actions. But researchers have had difficulty finding any effect of odors that we can't consciously identify. A team led by Wen Li saw procedural problems in those early studies: An odor that one person can't detect might still be obvious to someone else. Even the same individual might perceive an odor sometimes and not others ("I

thought I smelled smoke, officer!").

Li's team tried to correct those problems by giving 31 student volunteers individualized tests of their thresholds for detecting odors. They sniffed bottles containing progressively weaker solutions of three different odor-producing substances: Citral (lemon), Anisole ("ethereal" - a neutral scent), and valeric acid (sweat). For each substance, when each student could no longer detect the odor, a solution 56 percent weaker was chosen for use in the experiment.

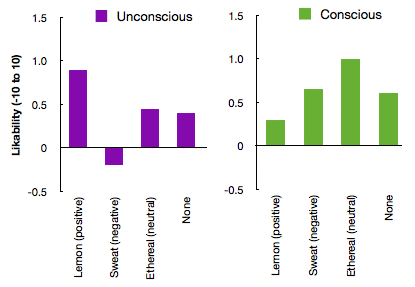

Next, these same volunteers were asked to rate photos of faces for likability. Before rating a face, they took a sniff from a random unlabeled bottle (from one of the four weak solutions), and indicated whether they detected an odor. Then they saw the face and rated how likable they thought the person depicted was. So even though the odor was undetectable, did it have an affect on likability? Turns out, it depends on the individual doing the rating. Despite being unable to detect a stronger odor in the pre-test, the responses of 15 of the students indicated (via a d' measure) that they did notice the smells while rating faces -- although they were still extremely doubtful of their abilities, and no one could accurately determine which smell was which. Here are the results:

Those who weren't conscious of the smells rated faces significantly more likable after smelling the lemon scent than they did after smelling sweat. There was no significant difference for any of the smells for those who were conscious of the odor. Some of the students wore heart rate monitors during the test, and heart rate went up following the sniffs when they were conscious of the odor. But if a student was unconscious of the odor, heart rate was likely to go down after a pleasant or neutral odor, and up after an unpleasant odor.

So it appears that even odors we can't detect have an effect on our impressions of faces -- even when it's quite clear that researchers are studying the relationship between odors and faces. In fact, Li's team thinks it might be possible that this knowledge might have caused the reaction by the conscious group: they may have been trying to counter the negative impression of a bad smell with a better rating. It's only when you're truly unconscious of what you're smelling that you can't consciously manipulate your preferences.

This makes some sense--in the real world, if you meet someone on a smoggy day, you may try to take that into account when judging their personality. But if there's no other explanation for a foul smell when you meet a new person (or if you don't consciously notice the smell), then you're more likely to form a negative assessment of them. Especially if they're late paying you for their newspaper subscription!

Update: I have a confession to make. Over a year ago, I reported on this exact study. Somehow it slipped my mind as I read the article again a few days ago, and I wrote an entirely new report on the same study. Only when I was Googling this morning for the article's DOI did I come up with my original report on this study! Someone on Twitter challenged me to post it and see if anyone noticed, so I did. No one noticed after over three hours and hundreds of page views. I guess it's a matter of collective amnesia -- and it suggests that we could all benefit from a reminder about great research every now and then! Here's the

link to the original report. Sorry about that!

Wen Li, Isabel Moallem, Ken A. Paller, Jay A. Gottfried (2007). Subliminal Smells Can Guide Social Preferences,

Psychological Science, 18 (12), 1044-1049 DOI:

10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02023.x

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter