That's the number of scientists who are outraged by the Kyoto Protocol's corruption of science.

© unknownFreeman Dyson is one of the world’s most eminent physicists.

How many scientists does it take to establish that a consensus does not exist on global warming?

The quest to establish that the science is not settled on climate change began before most people had even heard of global warming. The year was 1992 and the United Nations was about to hold its Earth Summit in Rio. It was billed as - and was - the greatest environmental and political assemblage in human history. Delegations came from 178 nations - virtually every nation in the world - including 118 heads of state or government and 7,000 diplomatic bureaucrats. The world's environmental groups came too - they sent some 30,000 representatives from every corner of the world to Rio. To report all this, 7,000 journalists converged on Rio to cover the event, and relay to the public's of the world that global warming and other environmental insults were threatening the planet with catastrophe.

In February of that year, in an attempt to head off the whirlwind that the conference would unleash, 47 scientists signed a "Statement by Atmospheric Scientists on Greenhouse Warming," decrying "

the unsupported assumption that catastrophic global warming follows from the burning of fossil fuels and requires immediate action."

To a scientist in search of truth, 47 is an impressive number, especially if those 47 dissenters include many of the world's most eminent scientists. To the environmentalists, politicians, press at Rio, their own overwhelming numbers made the 47 seem irrelevant. Knowing this, a larger petition effort was undertaken, known as the Heidelberg Appeal, and released to the public at the Earth Summit. By the summit's end, 425 scientists and other intellectual leaders had signed the appeal.

These scientists - mere hundreds - also mattered for naught in the face of the tens of thousands assembled at Rio. The Heidelberg Appeal was blown away and never obtained prominence, even though the organizers persisted over the years to ultimately obtain some 4,000 signatories, including 72 Nobel Prize winners.

The earnest effort to demonstrate the absence of a consensus continued with the Leipzig Declaration on Global Climate Change - an attempt to counter the Kyoto Protocol of 1997. Its 150-odd signatories also counted for naught. As did the Cornwall Declaration on Environmental Stewardship in 2000, signed by more than 1,500 clergy, theologians, religious leaders, scientists, academics and policy experts concerned about the harm that Kyoto could inflict on the world's poor.

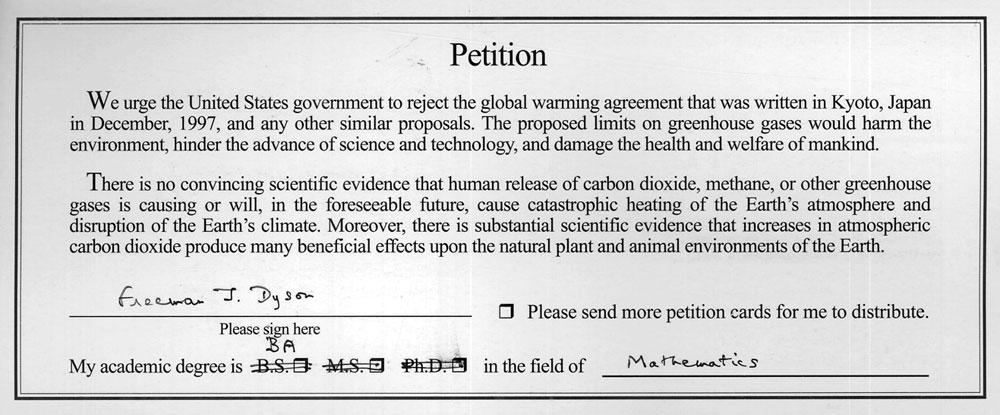

Then came the Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine's Petition Project of 2001, which far surpassed all previous efforts and by all rights should have settled the issue of whether the science was settled on climate change. To establish that the effort was bona fide, and not spawned by kooks on the fringes of science, as global warming advocates often label the skeptics, the effort was spearheaded by Dr. Frederick Seitz, past president of the National Academy of Sciences and of Rockefeller University, and as reputable as they come.

The Oregon petition garnered an astounding 17,800 signatures, a number all the more astounding because of the unequivocal stance that these scientists took: Not only did they dispute that there was convincing evidence of harm from carbon dioxide emissions, they asserted that Kyoto itself would harm the global environment because "increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide produce many beneficial effects upon the natural plant and animal environments of the Earth."

The petition drew media attention, but little of it was for revealing to the world that an extraordinary number of scientists hold views on global warming diametrically opposite to those they are expected to hold. Instead, the press focused on presumed flaws that critics found in the petition. Some claimed the petition was riddled with duplicate names. There were no duplicates, just different scientists with the same name. Some claimed the petition had phonies. There was only one phony: Spice Girl Geri Halliwell, planted by a Greenpeace organization to discredit the petition and soon removed. Other names that seemed to be phony - such as Michael Fox, the actor, and Perry Mason, the fictional lawyer in a TV series - were actually bona fide scientists, properly credentialed.

Like the Heidelberg Appeal, the Oregon petition was blown away. But now it is blowing back. Original signatories to the petition and others, outraged at Kyoto's corruption of science, wrote to the Oregon Institute and its director, Arthur Robinson, asking that the petition be brought back. "E-mails started coming in every day," he explained. "And they kept coming. " The writers were outraged at the way Al Gore and company were abusing the science to their own ends. "We decided to do the survey again."

Using a subset of the mailing list of American Men and Women of Science, a who's who of Science, Robinson mailed out his solicitations through the postal service, requesting signed petitions of those who agreed that Kyoto was a danger to humanity. The response rate was extraordinary, "much, much higher than anyone expected, much higher than you'd ordinarily expect," he explained. He's processed

more than 31,000 at this point, more than 9,000 of them with PhDs, and has another 1,000 or so to go - most of them are already posted on a Web site at petitionproject.org.

Why go to this immense effort all over again, when the press might well ignore the tens of thousands of scientists who are standing up against global warming alarmism?" I hope the general public will become aware that there is no consensus on global warming," he says, "and I hope that scientists who have been reluctant to speak up will now do so, knowing that they aren't alone."

At one level, Robinson, a PhD scientist himself, recoils at his petition. Science shouldn't be done by poll, he explains. "The numbers shouldn't matter. But if they want warm bodies, we have them." Some 32,000 scientists is more than the number of environmentalists that descended on Rio in 1992. Is this enough to establish that the science is not settled on global warming? The press conference releasing these names occurs on Monday at the National Press Club in Washington.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter