"It's a dramatic bay area," George Howard said. "In fact, I'd say it's one of the most dramatic."

Malcolm LeCompte, being more familiar with the area, cautioned, "That one that looks so prominent, it's just a flat field."

"Bay hunting is an exercise in the subtle," Howard agreed.

Howard, a Carolina bay enthusiast from Raleigh, and LeCompte, a remote imaging specialist from Elizabeth City State University, needed a bay. And they needed a bay they could dig in to look for minerals from outer space.

|

| ©The Virginian-Pilot |

Howard turned the car left onto Folly Road.

The Delaware Indians told Thomas Jefferson that long before his time the mastodon rebelled against the people it was created to serve, and a great battle was fought west of the Alleghenies. The other animals fought against the mastodon, and the Great Spirit came down from the sky and sat on a mountain to watch. Nearly all the animals were killed before the mastodon escaped, and swamps formed where their blood fell. Their bones, the Indians said, could be found there still.

So when Jefferson dispatched the Lewis and Clark expedition to explore the West in 1804, he asked them to also, please, keep an eye out for living woolly mammoths and mastodons.

Dwarf mammoths did, in fact, survive on an island off California for about 7,000 years after their enormous mainland cousins went extinct, but Jefferson received only bones from Lewis and Clark. Something had killed the giant animals of the last Ice Age, basically all at once.

In 2007, geophysicist Allen West and his colleagues suggested that the mammoth killer, in a maelstrom of fire and wind, may also have created the Carolina bays.

West is a calm man, so completely calm - philosophical, one might say, knowing his background - that the pursuit of catastrophe seems an ill fit. Yet the mystery of mass extinctions has drawn him since his childhood in Florida, where he learned that the arrowheads he picked up from the ground were used by prehistoric hunters to kill mammoths and mastodons.

"It struck me as a kid," he says, "that it seemed awfully odd, why would they go extinct after they'd been around for so long?"

He didn't pursue it. Instead, finding that a doctorate in philosophy didn't open many business opportunities, he went into geophysics, eventually forming a corporation that drilled for oil and gas. Now he is a consultant in Arizona, helping find oil, gas, groundwater and precious metals. He even located a lost Spanish mining tunnel for a client, or he thinks he did - it was very secret.

After retirement, he decided to write a book about mass extinctions. His research led him, ultimately, to the Carolina bays.

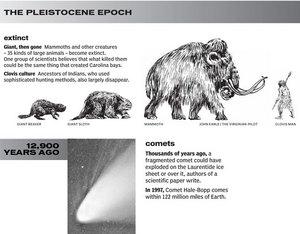

Ice ages come and go in regular cycles, each lasting about 100,000 years, and separated by shorter warm spells about 10,000 years long. But last go-around, as the Pleistocene ice age was starting to warm up, the Earth plunged back into cold conditions. Temperatures dropped about 20 degrees Fahrenheit, glaciers rebuilt, and 35 kinds of animals - not 35 species, but 35 groups of similar species - went extinct, just like that.

Never before had so many different animals disappeared in so short a time. The cold lasted for about 1,000 years, and then the planet abruptly warmed again.

This sudden cold spell is called the Younger Dryas. It marks the end of the Clovis culture, a people who had developed the repeating rifle of their day - a distinctive stone spear point on a reloadable shaft - for hunting mammoths and other huge creatures: giant ground sloths (similar to anteaters) that stood 10 feet tall, primitive horses, mastodons, short-faced cave bears larger than grizzlies, sab er-toothed cats and American camels.

Three theories have been proposed to explain the Younger Dryas extinction, known by their shorthand names of chill, ill and overkill. Proponents of the climate change theory say the drop in temperature, with its associated changes in habitat and food supply, snuffed the animals. Critics say the animals had survived previous ice ages just fine.

Pandemic illness has also been suggested, but there is little evidence of that.

The third theory is that Clovis humans, with their new and improved weapons, slaughtered the large animals to extinction, but critics say mice, hyenas, wolves, vultures and other small creatures also disappeared, and it is unlikely that they were overhunted.

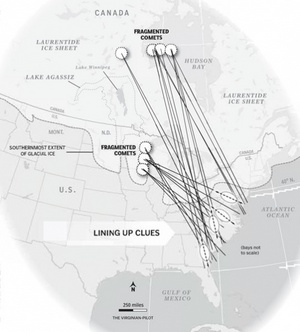

In 2007, 26 scientists from three nations, including West and Howard, proposed a fourth theory to explain not only the mass extinction but the Younger Dryas itself: A comet exploding over or on the Laurentide ice sheet that covered most of Canada and the Great Lakes.

"If you see white sand, we're passing a bay," LeCompte said from the back seat of the SUV. "I think that's a bay right there."

"Is it?" Howard asked doubtfully and kept going.

"Sure looks like we're coming over a rim here," West said.

Howard took a wrong turn, backtracked, turned again and stopped in the middle of a deserted road. The three exchanged maps and printouts.

"That was a cluster of bays we crossed," West said.

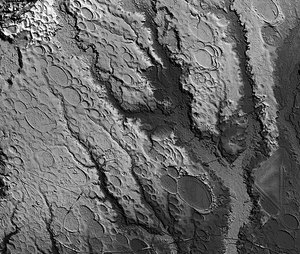

Everybody looked. Nobody saw anything. That is the big problem with Carolina bays. From the air, bays stand out like dimples on a golf ball, their white sand rims highlighting each oval. But from ground level, they are nearly impossible to see.

West has tried to find Carolina bays using GPS, and even then he has driven right past them. The three discussed downloading GPS coordinates on top of the Google Earth images where craters had been marked, and Howard tried to do that on his laptop while driving.

He finally pulled over by a sign that read "Sand Hill Farm" and let West take the wheel.

"Let's go to Rockyhock," West said.

The lead authors on the paper, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, are West and physicist Rick Firestone of the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab in California. The paper presents evidence that a comet may have wreaked havoc on Earth 12,900 years ago, at the start of the Younger Dryas. It is a refinement of West's book, published in 2006, when he, Firestone and a third author, in "The Cycle of Cosmic Catastrophes," proposed that a supernova could have set off a series of events culminating in a fragmented comet landing on the ice sheet or exploding over it.

"We believe what happened is that a large comet impacted the Earth near the Great Lakes, and that impact was sufficient to kill many of the mammoths outright," Firestone said in a phone interview. "The shock wave, a mega-hurricane of winds across the breadth of North America, actually caused much of the extinction. We believe the winds also formed the Carolina bays."

The theory covers a lot of ground: The blast melted the ice sheet, which sent floods of fresh water into the sea, which altered ocean currents, which caused the temperature to drop, which caused the Younger Dryas. In more detail, this is what the theory says happened:

|

| ©The Virginian-Pilot |

Comets are loose conglomerates of ice and dust and bits of cosmic leftovers, sort of like poorly packed meatballs. Meteorites and asteroids, on the other hand, are made of iron and rock. A comet would not necessarily leave a crater, especially not if it landed on an ice sheet several miles thick. But it would, like a meatball dropped into sauce, create quite a splatter.

The splat threw icy slush, dirt and radiation for hundreds of miles. Wildfires sparked by the extreme heat burned forest and grassland alike. Dust darkened sunlight and created rain clouds, which could have drizzled or poured for months, until the air cleared.

The impact or airburst would have melted ice, flooding the glacial lakes that already lay at the toe of the ice sheets. They would have burst their ice dams and roared away in all directions, ultimately pouring so much fresh water into the North Atlantic that the warm Gulf Stream was shorted out, a scenario portrayed in the 2004 movie "The Day After Tomorrow."

The authors say ancient stories from around the world tell of catastrophe. They share themes of something falling from the sky, of the world drowning in rain, of fires and floods and destruction. In many of them, the animals die and only a few humans - those who heeded warnings and obeyed heavenly commands - are spared.

LeCompte says scientists don't give much heed to Native American teaching stories, which he calls "white man's chauvinism." He's used to skepticism, having declared at the age of 4 or 5 that he wanted to be an astronaut, in the days before the job even existed. He ended up as a naval flight officer with a Ph.D. in planetary astrophysics.

He still remembers the sci-fi heroes who fueled his dreams - Tom Corbett, Space Cadet; Commander Corey and the Space Patrol; Rocky Jones, Space Ranger; and Captain Video - and he believes that the Indian legends are based on something just as amazing, but true. The Mattamuskeet of North Carolina call themselves "children of the falling star" for a reason, he says.

In "Cycle," the authors tell a Lakota story, about humans and giant animals becoming so evil that the Creator sent his Thunderbirds to fight them. They threw down thunderbolts from the sky that shook the world, setting forests and prairies on fire with flames that leaped to the sky. Lakes boiled and dried up, rocks glowed and the giant animals burned up.

Then the Creator sent rain to flood the Earth and cleanse it. After the floods subsided, the few people who survived found the bones of the giant animals buried in rock and mud.

Some researchers say the bays are 100,000 years old; others say 10,000 to 13,000. Still others say different bays formed at different times over millions of years; however, they cannot explain why Carolina bays are not still forming today.

In 1975, Rockyhock Bay was reported by D.R. Whitehead to be 35,000 years old, based on core samples, which are long tubes of rock and soil with the youngest layers at the top and oldest at the bottom. Another scientist, working on another bay, had reported finding ancient river channels and other old sediments underneath his bay. West thought it was possible that Whitehead had cored too deeply and had analyzed samples that actually came from underneath Rockyhock Bay, not from the bay itself.

If he could show that the 35,000-year-old layer reported by Whitehead extended beyond the edges of the bay, it would support the idea that the bays are younger, perhaps only 12,900 years old.

Especially if he could find diamonds.

Tomorrow: Searching for evidence

|

| ©The Virginian-Pilot |

Diane Tennant, (757) 446-2478, diane.tennant@pilotonline.com

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter