Cloud-seeding, you may be thinking, went out of fashion decades ago, perhaps in 1969 when the hippies swore that it was CIA scientists fiddling with nature who caused the downpours at the Woodstock music festival. Not so. In fact, it seems to be more in vogue than ever, in California and elsewhere.

|

| ©The Independent |

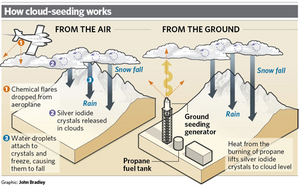

This, although there is not a scientist on the planet who can swear hand-on-heart that the practice of firing silver iodide into unsuspecting clouds is actually responsible for elevated precipitation. Say the cloud indeed lets loose a deluge, who is to say it wouldn't have done so anyway?

But scepticism is not stopping Los Angeles County giving it a go anyway. Officials have announced that next winter they will spend almost a million dollars trying to seed clouds over the San Gabriel Mountains north of Los Angeles, hoping to fill reservoirs with increased rainfall.

And it will not be the first time they have tried it. They did it for years until a wild storm 30 years ago triggered landslides in the foothills that killed 11 people. Local families sued the county because it had been cloud-seeding at the time. They resumed seeding in 1991 and stopped again six years ago.

"It's a bit of a sign of desperation," Peter Gleick at the Pacific Institute, told the Los Angeles Times. "They've been doing cloud-seeding for decades, but we've never clearly been able to show if it's what we've done or what nature has provided."

Maybe seeding makes no difference at all. Maybe it creates tempests so fierce that they cause landslides. County officials say that the effects are more moderate, a 15 per cent increase in rainfall. "We're basically coaxing Mother Nature," says the county civil engineer, William Saunders. At least he has the comfort of knowing he is not alone in putting faith in rickety seeding science. They do it in other parts of the US: electricity utility companies are especially fond of seeding to bring more water to hydro-electric plants, and seeding is popular with authorities in Russia and China too.

Residents of Moscow have just been reminded that for years the Russian air force has been in the habit of trying to coax moisture out of clouds to ensure sunshine on national holidays. Among materials they chuck into the skies from circling planes is cement. It is meant to spread and pulverise way up there but this week a 55lb sack of cement that remained intact fell all the way to Earth, and through the roof of a house.

But no country is more committed to researching weather modification than China, with a national budget in the tens of millions of dollars, and thousands of miles flown by rain-seeding aircraft every year. And the biggest test for China is just around the corner. The authorities are hoping to use seeding technology during the Olympic Games, both to ensure clear skies for the opening ceremonies (August is the capital's rainy month) and to induce gentle night-time showers to cleanse the air of pollutants.

Visitors to the Games and athletes will have to judge for themselves whether the investment in cloud manipulation pays off. Probably best to take a brolly anyway.

Comment: See: Russia: Sometimes it rains cement.