The Aztecs lived in Mexico in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries and are most famous for their human sacrifices, notably by heart removal.

|

| ©Library of Congress |

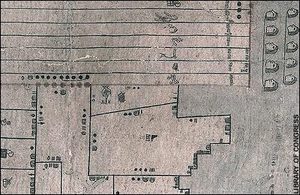

| Drawn in 1540 CE, the Oztoticpac Lands Map despicts property dimensions of lands near Texcoco |

Profs Barbara Williams of the University of Wisconsin, and María del Carmen Jorge y Jorge of the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico in Mexico City, Mexico, report in the journal Science that the Aztecs used their own form of arithmetic, which included hearts, hands and other symbols as alternatives to fractions, to measure and record the areas of land parcels.

Just as modern governments require careful land surveys and records of value for taxation, Aztec administrators were diligent book keepers when it came to landholdings and real estate.

But rather than using a decimal system, based on the number of fingers, they used a "base 20" system, as opposed to how the decimal system is based on ten.

This requires 20 individual numerals (or symbols), ten more than we use.

"They didn't have a decimal system, they used base twenty number system based on fingers and toes," says Prof Jorge y Jorge, who calls this "Acolhua Congruence Arithmetic."

Although the Spanish wiped out most of Aztec culture after their conquest, two ancient manuscripts of Aztec origin from the 16th-century, the codex Vergara and the Santa María Asunción codex, carry key details of land ownership in the region of Texcoco (nearby Mexico city), one of the three most important kingdoms in the Valley of Mexico encountered by the Spanish.

They belong to the Acolhua culture, who like other Aztecs did not have an alphabet but used symbols, like the Ancient Egyptians.

In the first part of each codex there is a detailed census of the families inhabiting the towns there. In a second section landholdings of each household are depicted.

Distances of each field side are shown by Acolhua/Aztec numerals of lines (one unit) and dots (20 units).

The lines and dots refer to the Acolhua's standard measure, called a land rod, of approximately 2.5 metres.

Occasionally sketches of a hand, an arrow or a heart (called monads), were also drawn on the field sides, which represent distances and shorter than the standard unit.

In the last section of the codex, the household landholdings are shown again with an entirely different notation. In 1980, Prof Williams, working with the late Prof Herbert Harvey, deciphered this notation and showed that it refers to the corresponding areas of the fields.

From the field areas, Profs Williams and Jorge y Jorge could glimpse the arithmetic used by the Acolhua-Aztecs. Like the Sumerians and Romans, they used the "Surveyor's rule," where area equals the product of the average length of opposite sides, which is handy for fields that are not ideal squares.

They could then use these rules to check that the Aztecs did indeed use fractions, and work them out by also using colonial-period native and Spanish documentary evidence.

"We established the proportions as: Two arrows = one land rod, five hearts = two land rods, five hands = three land rods, five bones = one land rod, and three arms = one land rod."

They were sure they were correct because they could compute the exact areas recorded by the Acolhua in the case of 287 fields.

But the Aztecs did not use fractions as we understand them. So rather than thinking of half a land unit they used an arrow instead and would do the same mental calculation as we do today when converting minutes into hours, hours into days, inches into feet, and so forth.

"For example, using the above proportions, five times an arrow, will be two land rods plus one arrow, eight times a heart will be two land rods plus three hearts and six times a hand will be three land rods plus a hand."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter