The rediscovery of this book is of much more than scholarly or antiquarian interest, for it has been suggested that its chess puzzle diagrams were not only designed by Leonardo da Vinci, but also drawn by him and, the most tantalising prospect of all, perhaps even composed by him.

|

| ©Unknown |

The book, De ludo schacorum (about the game of chess), was written by the Renaissance mathematician Luca Pacioli who lived from the mid-15th century to early in the 16th. The so-called new chess, which considerably enhanced the powers of the pieces, was introduced around the 1470s. Pacioli's long-lost book was said to be a series of educational positions and chess puzzles featuring both the old and new styles of chess - the latter known as a la rabiosa (with the mad or angry queen), because of the vastly extended powers of this new piece.

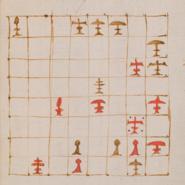

The puzzles showing the new chess were rumoured to have been composed to demonstrate how the fresh powers of queen, bishop and pawn truly functioned on the open board. However, Pacioli's book was lost and doubts were raised that it had been written at all. Now the book has resurfaced from the 22,000-volume library of Count Guglielmo Coronini, and facsimiles have been published with strange and rather beautiful diagrams in red and black showing the pieces in action.

Recently The Guardian published a puzzle from the book with a commentary by its chess correspondent who conceded that he "did not have the foggiest idea" what the puzzle meant or whether it was taken from the old or new style of chess.

Having had time to examine the puzzle more closely, I have established that it is definitely the new rabiosa form of chess which we still play now. I have also worked out that there is a fiendishly difficult forced checkmate from the puzzle position.

This is amazing, since the new chess had been in existence for only a few years when the book was written. Given its relative novelty, the person who composed this puzzle was evidently a chess genius.

As well as being highly advanced for its time, the solution also succeeds brilliantly in its didactic purpose of showcasing the sweeping new powers of queen and bishop as well as the potentially devastating weapon of a humble pawn now being able to promote to a mighty queen. Normally this would end the contest in the promoter's favour. However, in this puzzle the losing side even manages to promote to a queen with check, yet still succumbs.

What about Leonardo da Vinci's involvement, as suggested by the owners of the book, the Fondazione Coronini Cronberg?

The standard chess history by Richard Eales, of the University of Kent, confirms that this shows the new chess quickly interested leading intellectuals in Renaissance Italy - the kind of people in Leonardo's circle, even if his own role remains tantalisingly unprovable.

Pacioli and Leonardo were associates, and it is recorded that Leonardo provided illustrations for Pacioli's work on the mathematics of the golden mean, De divina proportione. Both men fled from the court of Ludovico Sforza in 1499 when the French attacked Milan and both were protected by Isabella d'Este, a chess enthusiast who possessed various chess sets. She has been tentatively identified as playing chess in a late Quattrocento panel in the Metropolitan Museum, New York, once attributed to Francesco di Giorgio, c. 1485, and more recently to Liberale da Verona.

I believe that Leonardo did not draw the main corpus of puzzle diagrams for the book. However, he may well have supplied the original designs for the pieces. These are shown in array at the start of the book and they are artistically superior to the diagrams which follow in the text, which are unambitiously redrawn copies. The owners suggest that the original design for the queen, for example, is almost exactly identical to Leonardo's design for a fountain in his so-called Atlantic Codex. Others contend this type of design could easily be generic.

Finally, there is the alluring possibility that Leonardo himself composed the problem.

Contemporary books about the new chess are exceedingly rare, and the few we do have tended to concentrate on a few puzzles which subsequent authors simply copied.

However, as Richard Eales says, "nothing like this puzzle has so far been found in other publications, or the older manuscripts or printed chess books". Furthermore, the diagrams are stunningly different from anything else of its day. The possibility that Leonardo did compose this puzzle is enticing and by no means impossible.

In the puzzle it should be noted that Black is in check from the white bishop on e4 yet both kings are in serious danger and could easily fall prey to a sudden checkmate.

With both sides clinging to a precipice, the fact that White has the initiative conferred by the bishop check annihilates both of Black's two principal defences.

It should also be observed that there is an illegal white pawn on d1 in the original. I have replaced this with a white knight, which makes no difference to the solution. It is possible that the original Renaissance copyist put down a pawn instead of a knight - or after the massive rule changes around 1475 there may have been some local disagreement about the laws of the game which might perhaps have permitted a pawn to move backwards.Somehow, though, I doubt this and favour the solution that implies a miscopied piece.

Only a powerful intelligence could have devised the puzzle and the solution, which would tax the mental powers of most strong players even today and in its complexity and richness could only really be solved easily by a computer. The evidence of a commanding intellect behind this chessboard conundrum is palpable indeed.

Chess: The History of a Game by Richard Eales is available here

Information on De ludo schacorum Link

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter