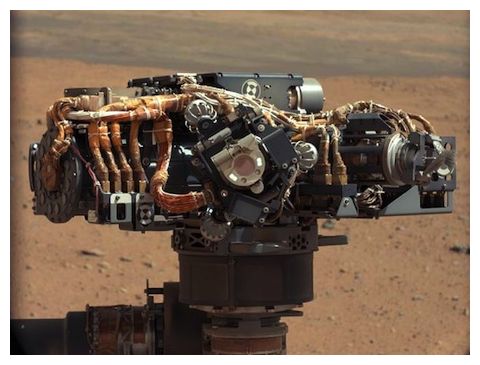

This is the moment the scientists have been waiting for. Nasa's Mars Curiosity rover will begin driving today in search of the first rock to analyse with its robot arm. After five and a half weeks of instrument checks, software updates and test drives, today the scientists take over from the engineers.

Searching for the right rock could take days or weeks depending upon what the rover happens to pass. Curiosity will make slow but steady progress, driving at no more than 40 metres per Martian day, or sol as the scientists call them, before radioing its progress back to Earth.

From now on, the science team will meet as soon as the data is received to determine what has been achieved and what they would like to do next. This could be driving to a new location, analysing a rock or soil sample, or taking images.

The decision-making process is split across two eight-hour shifts. During the first, the scientists make a plan that the engineers check to ensure it is achievable. During the second, programmers build the command sequences necessary to make the plan happen. These are uploaded to Mars and Curiosity sets about following them, while the ground team grabs some rest.

If anything unexpected happens, perhaps Curiosity tilts beyond a preset limit or slips too much in the dust while moving, then it will stop what it's doing, send its status back to Earth and await further instructions.

The science mission begins with Curiosity in excellent shape, and with an operating crew brimming with confidence. During a teleconference on Wednesday, Jennifer Trosper, the mission manager from Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told how the expertise built up across previous rover missions was paying off.

During 1997's Mars Pathfinder mission, one in three sols were lost because something happened unexpectedly and the rover halted operations. During the Spirit and Opportunity rover missions, which landed in 2004, lost sols were down to just one in 10. So far, Curiosity has clocked up 37 sols on the Martian surface yet they are just a single sol over their expected mission plan.

Ironically, given the amount of geological instrumentation on the rover, today's first scientific observation will not be looking down at rocks but up into the sky. Twice every Martian year (which is about twice as long as an Earth year), Mars's largest moon, Phobos, slips across the face of the Sun. It happens today and the team will try to record the event.

Then Curiosity begins to "drive, drive, drive". Today is not the first time the rover has driven. There was a 13-sol period during the checking out phase called the intermission when Curiosity drove 109 metres to test its ability to manoeuvre. Today, however, the driving begins in earnest.

Using just 115 Watts of power - a little more than a traditional, bright lightbulb - it will head for a rock formation dubbed Glenelg. Ostensibly named after a rock formation in Yellowknife, Canada, Nasa also chose the name because it is a palindrome and they plan to visit the formation twice.

Wherever they go after this first foray, they will have to pass by Glenelg again from the opposite direction when they turn around and head back to their primary target, Mt Sharp. Why not just head straight there? Even on Mars, it seems, the temptation to take the scenic route is irresistible.

Let the science begin!

Stuart Clark is the author of The Sky's Dark Labyrinth (Polygon)

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter