With much of the corn crop already lost, farmers are holding out hope for some weather relief that could help salvage the harvest of soybeans and other. But the latest data from the government Friday showed that the damage to the food supply chain already has been done.

"This is worse than 2008 -- we're in kind of a perfect storm scenario," said Ana Puchi-Donnelly, senior agricultural commodities trader at London-based Marex Spectron. "We won't really know until the whole crop is harvested. We're talking about the worst drought in the last 50 to 70 years in one of the hottest years on record."

Shriveling supplies have sent grain prices soaring. Corn futures set an all-time high Friday to levels roughly 50 percent higher than the end of May, before the drought took hold. Soybean prices also jumped this week to more than 25 percent above pre-drought levels.

While those price spikes have yet to work their way through the food chain, American consumers can expect to pay more to put dinner on the table. The overall impact on food prices, however, is expected to [be] relatively small.

"If you're a family of four on a tight budget, it's not inconsequential," Gregory Page, CEO of Cargill, one of the world's largest food producers, told CNBC. "But to put it in context, it is about $75 per man, woman and child here in the U.S. vs. the levels we saw a year ago."

The outlook for this year's harvest has changed dramatically over just a few months. In the spring, U.S. corn farmers planted the most acreage in 75 years and expected a record harvest. Countries that rely on the United States as the world's largest food exporter were hopeful the yield would replenish depleted global stockpiles.

But those hopes have been dashed as farmers sift through their drought-parched farmlands. The government's latest estimate of this year's harvest, released Friday, was even worse than expected. After predicting a bumper crop of nearly 15 billion bushels of corn in June, the USDA Friday predicted a harvest of less than 11 billion bushels, 13 percent below last year's level.

Expected corn yields were slashed from June's estimate of 166 bushels per acre to just 123 bushels, some 25 percent below normal. Inventories of soybeans, widely used as livestock feed from India to Indiana, will be the smallest in nine years.

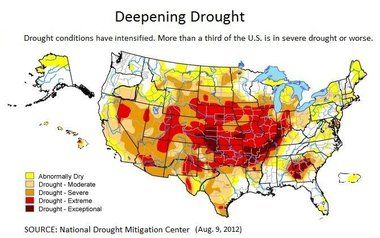

There is little sign of relief in the weather forecast. The severest conditions - - which have already enveloped more than a third of the nation - - continued to spread this week, according to a report Thursday from the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska. July was the hottest month on record, beating the worst month of the Dust Bowl era in 1936. After mild weather allowed farmers to plant earlier than normal this year, modest rainfall in parts of the Midwest this week came too late for much of the crop.

"There will be some improvement; the cooler temperatures certainly will help," said Andy Karst, a meteorologist for World Weather. "But most of the Midwest has not had enough rain for significant improvement. Crops may stabilize or decline a little more the next couple of weeks."

Though food inflation in the U.S. so far has been relatively tame, the surge in crop prices is expected to move quickly through the global food chain, pushing up prices of beef, poultry and other processed foods.

Cattle ranchers already are dipping into stockpiles of hay set aside for winter after the drought killed much of the grass forage they typically rely on during the summer months.

"We don't have much hay, we don't have much corn, we don't have much of really anything," Brett Crosby, a cattle rancher in Cowley, Wyo., told CNBC. "Over half of the pastures in the United States are rated poor to very poor in condition."

The U.S. crop shortfall comes as the rest of the global supply chain is already under pressure. Hot weather in Russia and too much rain in farmlands in Brazil have lowered crop yields, further straining inventories.

Demand, meanwhile, remains strong in the developing world, even as the global economy slows. The shrunken forecast for this year's crop has raised concerns that the world could see another repeat of the severe shortfall in 2008 that led to food riots in some countries.

"Supplying countries put on embargoes against exports and we had importing countries that in many cases were buying more than they actually need," said Page. "The combination of those two actions by governments exacerbated the sense of shortfall and I think accelerated the price increases."

Page this year's expected shortfall -- between 3 and 4 percent below the long-term trend in production levels -- is "manageable, if we make good decisions."

That effort would require a coordinated global effort by governments to head off potential bottlenecks that produced big food price spikes in 2008. Those moves could include scaling back government subsidies put in place to promote biofuel production, which has diverted corn and soy supplies.

"Several urgent actions must be taken to address the current situation to prevent a potential global food price crisis," said Shenggen Fan, head of the International Food Policy Research Institute, a think tank funded by the World Bank.

Reuters contributed to this report.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter