© NBC News

As the U.S. economy limps along into its fourth year of a tepid recovery, its job creation machine remains badly broken.

Friday's monthly employment report was better than many forecasters were expecting, showing a relatively strong gain of 163,000 new jobs in July. But the rise of the jobless rate - - up a tenth of a point to 8.3 percent -- was a painful reminder of how many sidelined workers have been left behind by the weakest rebound in six decades.

As the subpar recovery drags on and growth appears to be, in the words of Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, "stuck in the mud," the weak pace of hiring may be doing lasting damage.

"You destroy human capital, and the problem is it's difficult for those individuals to come back," said Ed Lazear, a Stanford economist who served as adviser to President George W. Bush. "People who are in their mid- to later 50s -- who would otherwise be working for another 10 years or so -- now may simply decide to stay out of the labor market. That's a lot of lost manpower and lost productivity."

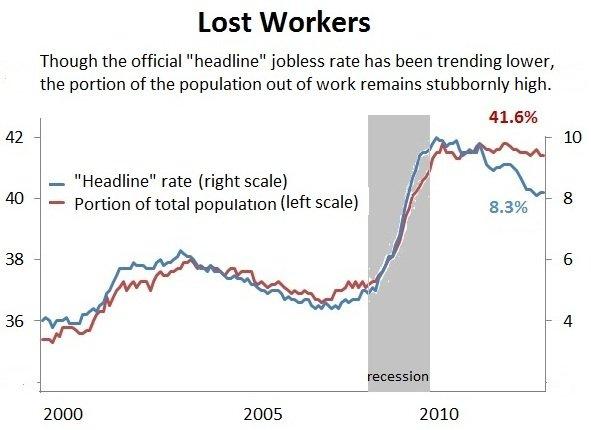

Though the headline jobless rate that attracts the most attention in the media has been trending lower from a peak of 10 percent in 2009, that doesn't capture the large group of Americans who have given up looking for work.

The government isn't hiding the data. The Bureau of Labor Statistics has been tracking unemployment as a percent of the population, for example, since 1948. By that broadest measure, some

41 percent of the total population over 16 is not working -- a rate that has barely budged since the recession ended in June 2009.

Another measure, the labor participation rate, shows that the share of working-age Americans who are either working or looking for a job has fallen to levels not seen since the early 1980s, when fewer women chose to do paid work. The share of men in the labor force is down to about 70 percent, the lowest level in the more than six decades that the Labor Department been tracking the data.

Though economists and politicians don't agree on why the economy's hiring machinery is sputtering, there's widespread consensus that millions of jobs go unfilled in the U.S. because employers can't find skilled workers. There's less agreement, though, on where the money will come from to train those jobless workers. Nobody, it seems, wants to pick up the tab.

But the importance of education and training are clear: Workers with college and professional degrees earn substantially more than those with only high school diplomas. That's lost income that would otherwise add to the gross domestic product. As college tuition costs continue to outstrip inflation and wage growth, those credentials remain out of reach for many potential students.

There's also a mismatch between the skills being taught in schools and those actually needed in the workplace - even at colleges and universities. Among the class of 2011, for example, engineering dominated the list of top-paid majors, according to the National Association of Colleges and Employers. But of 1.6 million bachelor's degrees awarded in 2009, fewer than 90,000 were in engineering.

Though younger workers are having a harder time getting careers started, older workers are at greater risk of leaving the workforce - whether by choice or not. Among unemployed workers 45 and older, nearly 11 percent had been out of work for 99 weeks or more, according to a 2010 study. By contrast only 6 percent of the unemployed under 35 had been out of work that long, according to Congressional Research Service study.

Though the study found little difference in long-term unemployment based on the level of education or gender, married workers were more likely to have been jobless for 99 weeks or more, as were black workers.

The cost of so many people out of work for so long is impossible to calculate. But a full accounting starts with the human costs to those unable to find a job.

"

A large literature in economics and sociology has shown that unemployment correlates strongly with the incidence of depression, low self-esteem, unhappiness, and even suicide,"

according to a paper by economists Till von Wachter and Dan Sullivan.

By matching job loss data with Social Security death records, the two researchers estimated that the mortality rate for "high-seniority" male workers in the year after a job loss is 50 to 100 percent higher than for their employed peers. Even 20 years after a job loss, the mortality rate was 10 to 15 percent higher.

The joblessness also has a wide impact on the economy, with fewer workers contributing to the growth of overall economic output and consumer spending, which accounts for roughly 70 percent of GDP.

The result is something of a vicious circle: Fewer workers means less spending which holds back growth that would otherwise prompt employers to boost hiring.

To be sure, there may be other reasons consumers have pulled back. Older households, whether voluntarily retired or simply unemployed for life, spend more cautiously as they transition to life on a fixed income. That demographic shift, as baby boomers enter a lower-spending phase of life, will likely weigh on consumer demand for years to come.

Many households, meanwhile, are still trying to pay off large piles of debt after taking on too much during the borrowing binge of the 2000s. Others may be may be spooked by the prospect of looming federal tax increases and spending cuts set to hit at year end. Those would almost certainly spark another recession unless Congress finds a compromise.

"There are a lot of question marks that are going to be answered in November," said Pierpont Securities chief economist Stephen Stanley. "Until then a lot of people have just pulled in their horns."

We are stuck in the economic mud.

That is precisely where they want us, and intend to sentence us.

In Economic Folsom Penitentiary, with no chance of a pardon.

"I shot an economy in Reno, just to watch it die".