To the question "What did you do on your summer vacation?" many teenagers will presumably return to school in September answering: "I helicoptered back and forth between Cap Ferrat and St.-Tropez." In one of the original photos, a toddler on a private jet is strapped into a car seat and staring at a computer screen. How uplifting it would be to learn that he was watching The Muppets Take Manhattan and not Jim Cramer's Mad Money.

These images have come along to provide a fitting scrapbook for a season in which the religion of selective reality seems only to be gaining adherents. Consider the fictions that have taken hold in regard to New York City's economy. "Bloomberg's NYC Jobs Miracle; Exaggeration? Maybe Not," read a particularly delusional headline in Crain's New York Business two weeks ago. In early July, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, reiterating one of his administration's memes, pointed to the successes of "film and television production, tourism, commercial bioscience and the city's rapidly expanding tech sector" as reasons that New York has recovered from the recession "far more robustly" than the rest of the nation.

This, of course, is a highly dubious claim. Despite job growth in certain knowledge-class and service sectors, unemployment has been rising. On Thursday, the State Labor Department reported that the city's unemployment rate climbed to 10 percent in June, exceeding the national figure by close to two percentage points. The unemployment rate in the city is now nearly twice what it was five years ago and has been running higher than the figures for Atlanta, Boston, Houston and Chicago.

While it is indeed a very good time to be moving to New York with a Stanford M.B.A. and a business plan to create the Twitter of 2014 (as suggested by the barely post-adolescent tech entrepreneur Josh Miller when he stood next to the mayor at a press event in May), it is a far less auspicious moment to be someone who already lives here and is looking for cleaning work, say, in the offices of the Twitter of 2012.

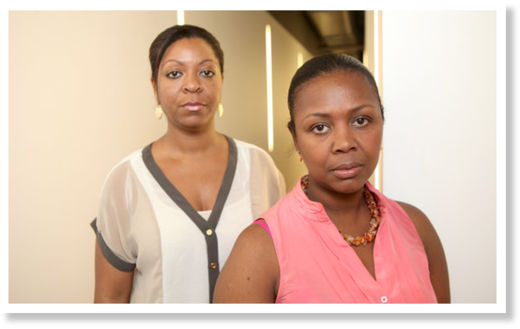

Since last month, Agustina Guillot and Lorena Ordonez, middle-aged immigrants living in New York, have been seeking jobs in the aftermath of being let go, with little explanation, by a company contracted by Con Edison to clean its headquarters in Union Square.

It had taken Ms. Guillot five months to find the position last year, she told me, after she and her 23-year-old son were both laid off from factory jobs at an electronics manufacturer in New Jersey. Her son has been unable to find any work for 16 months.

Ms. Ordonez, a single mother who lives in the Bronx and came to the States from Ecuador in 1981, was already working full days as a home health aide in East Harlem when she accepted the 5 p.m. to 1 a.m. cleaning shift at Con Edison, embarking on a schedule and route - multiple subways and two-hour trips in the middle of the night - that allowed her no more than three hours of sleep.

Because she is paid so little beyond minimum wage, she requires two full-time jobs to meet expenses that include a rent burden of $1,475 a month, on which she is now 60 days behind. (Someone might alert Anne-Marie Slaughter, the author of a notorious article in The Atlantic on "equal opportunity for all women," that this is how the 80-hour workweek materializes for women who don't ask, "Can I have it all?" but rather "Can I get enough?")

If worker satisfaction - the extent to which people feel engaged with what they do, invested in the companies they work for and rewarded and respected for their efforts - is regarded as an indicator of economic and social well-being, then the city is in far from exemplary shape. Many low-wage workers in the city don't receive paid sick days, and a measure to require employers to provide them is stuck in the City Council.

A report released last week and written in part by UnitedNY, a group that has large-scale protests on behalf of low-wage workers planned for Tuesday, carefully delineates the constraints under which these workers operate and the disparities between what low earners make and the profits their employers reap. In the 1960s and '70s, the report states, the earnings of someone working full time, year round at the minimum wage were enough to lift a family of three above the poverty line. The purchasing power of New York State's minimum wage, which stands at $7.25 an hour, is now dramatically lower than it was 40 years ago. Today, a person earning the minimum and working year round would earn about $16,000, or 82 percent of the poverty threshold for a family of three.

Included in the study is a list of what are labeled the city's worst low-wage employers and industries, those that pay inadequately and fail to offer decent benefits. Among them: airline contractors that provide baggage handlers, cabin cleaners and front-line terminal security at the city's airports. At J.F.K. last week, I met a security worker, Prince Jackson, employed by Air Serv (whose chairman, Frank A. Argenbright Jr., the report handily tells us, owns a $6.8 million compound in Sea Island, Ga.) as he ended a night shift. Part of his job involves the important work of monitoring a passenger-exit area in a Delta terminal, ensuring that no one breaks through into the arrivals area.

For this he is paid $8 an hour. His health plan's co-pay is too high, so he never uses it, he told me. Mr. Jackson, who is galvanizing his co-workers and speaking at Tuesday's event, said that were it not for his church's food pantry, he could not afford groceries. His son is a junior at Clark University, and he would like to be able to send him some money occasionally so the young man could study more and work less. But he can't.

Forget uncorking the Roederer Champagne on the way to the Vineyard.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter