© AP

PARIS - The break that had long eluded the political career of 57-year-old French Socialist François Hollande finally surfaced with a text message in the wee hours of May 15 last year.

His girlfriend, 47-year-old journalist Valérie Trierweiler, read it and nudged Mr. Hollande awake: Dominique Strauss-Kahn - then-chief of the International Monetary Fund - had been arrested by police in New York on suspicion of sexual assault. "François did not grill me for more details about the arrest," Ms. Trierweiler said. "He was already thinking of his next move."

The French Socialist Party had been counting on Mr. Strauss-Kahn to defeat President Nicolas Sarkozy and regain the reins of the world's fifth-largest economy after an absence of 17 years.

The arrest and ensuing scandal, instead, cleared an unlikely path for Mr. Hollande, long dismissed by his own party as a chubby apparatchik and political lightweight. The closest Mr. Hollande had come to occupying the Élysée presidential palace was the 2007 presidential candidacy of Ségolène Royal, his longtime companion and the mother of his four children.

Ms. Royal announced their split in a radio interview the morning after she was trounced by Mr. Sarkozy, who is now seeking a second term. Soon after, Mr. Hollande made public his relationship with Ms. Trierweiler, a political reporter who had covered Ms. Royal's campaign.

Mr. Sarkozy, holding the benefit of incumbency, seeks to highlight Mr. Hollande's backbench reputation to voters. "Can you tag Mr. Hollande's name to a single idea?" he asked reporters at a recent news conference.

Even Michel Sapin, a former Socialist finance minister and now a top adviser to Mr. Hollande, said that was a problem: "A year ago, asked what François thought about this or that issue, nobody could answer."

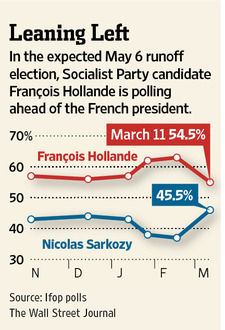

A survey released Tuesday by French polling agency Ifop points to a first-round win by Mr. Sarkozy in the April 22 election but a victory by Mr. Hollande in the expected May 6 runoff, 54% to 45%. Mr. Sarkozy's popularity is tarnished by unemployment and government austerity measures springing from Europe's sovereign debt crisis.

If Mr. Sarkozy loses, the 57-year-old president would be the 11th euro-zone leader swept away in the crisis, from the flashy Silvio Berlusconi in Italy to George Papandreou in Greece, as Europeans look to more technocratic leaders.

Mr. Hollande, who won the French Socialist Party nomination in October ahead of more left-leaning candidates, has shed some of the left's rhetoric to embrace a more pragmatic campaign platform.

Despite some differences over where to trim government spending, Messrs. Hollande and Sarkozy both aim to shrink France's budget deficit below the European Union's ceiling of 3% of gross domestic product.

To rally his base, Mr. Hollande has coated his electoral platform with a left-leaning varnish, describing the world of finance in January as his "main adversary." He wants to raise tax rates from 41% to 75% for people earning more than a million euros, or about $1.3 million, a year.

Mr. Hollande has proposed softening the impact of an increase of the pension age to 62 years from 60 - a change introduced in 2010 by Mr. Sarkozy. The Socialist candidate said he would allow workers who contributed to the deficit-choked pension system for at least 42 years to continue retiring at 60.

Mr. Hollande has called for reducing France's reliance on nuclear power, which meets nearly 80% of the country's electricity needs, and said the country must accelerate the withdrawal of its troops from Afghanistan.

He said he would force banks to exit tax havens but has distanced himself from the legacy of France's last Socialist president, François Mitterrand, who nationalized most of the country's banks and industrial companies in 1981.

In seeking another five-year term, Mr. Sarkozy hopes to capitalize on his management of the euro crisis. The tandem formed by Mr. Sarkozy and Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel has emerged as the driving force behind most euro-zone decisions, but Berlin often appeared to have the upper hand.

Mr. Hollande has promised to rebalance his country's relationship with Germany, saying he would challenge Ms. Merkel's insistence on fiscal austerity and focus instead on boosting growth. He has offered to meet Ms. Merkel ahead of the election, but the German leader has yet to agree.

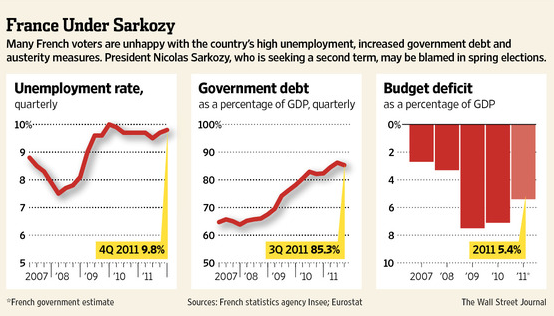

Many voters are unhappy with the country's unemployment rate of 9.8% and the recent stripping of France's triple-A credit rating by Standard & Poor's Ratings Services.

Some are irked by Mr. Sarkozy's personal life. After his election, his second wife Cecilia filed for divorce. Mr. Sarkozy began dating singer and former supermodel Carla Bruni. They married and had a child. A well-publicized lifestyle, including time aboard a billionaire's yacht, earned Mr. Sarkozy a nickname: the bling-bling president.

Mr. Hollande, who casts himself as a "normal man" compared with the president, said it was frustrating to see voter support not for his ideas but over resentment of Mr. Sarkozy. "For now, the echo I'm receiving is a rejection of Mr. Sarkozy," Mr. Hollande told reporters over lunch recently.

Mr. Sarkozy, a savvy campaigner, is trying to boost morale. "Don't you worry," he told members of his ruling UMP party in February, said people there. "We are not lepers."

His Socialist Party challenger has been close to the spotlight but never its subject. In fact, Mr. Strauss-Kahn's political fall was a rare bit of luck for a career otherwise marked by missed opportunities.

Mr. Hollande was born in Normandy to a "rather conservative family," according to his own description. His mother was a social worker, and his father, a doctor, made a few runs in local elections under the banner of far-right movements in the late 1950s and mid-1960s.

At age 13, Mr. Hollande, his elder brother and parents moved to Neuilly-sur-Seine, the upscale suburbs near Paris that would later become Mr. Sarkozy's electoral stronghold.

In 1978, Mr. Hollande joined the Ecole Nationale d'Administration, France's elite administrative school, which boasts as alumni two presidents and a long list of prime ministers. There, he began his relationship with Ms. Royal, who had also joined the Socialist Party. Among their other classmates were Dominique de Villepin, who became a prime minister, Henri de Castries, now head of French insurance giant AXA SA, and Jean-Pierre Jouyet, who heads France's stock-market watchdog.

After graduation, Mr. Hollande enrolled in the prestigious administrative corps of the Cour des Comptes, the national audit office, where technocrats crisscross the country to crunch the numbers of state agencies and local governments. At the same time, he and Ms. Royal joined the campaign staff of Mr. Mitterrand, who was running for president in 1981. She was 27 years old, and Mr. Hollande was 26.

© Wall Street Journal

Mr. Mitterrand won the election, and the couple followed him to the Élysée to work as junior advisers. During the legislative election that followed Mr. Mitterrand's victory, Mr. Hollande staged an audacious move: he challenged Jacques Chirac, then the leader of the conservative camp, in the rural constituency of Corrèze in central France.

Mr. Chirac, who had already served as prime minister in the 1970s, said his rival for a seat on the National Assembly was "less known than Mr. Mitterrand's Labrador." Mr. Hollande lost but settled on Corrèze as his political home base, even though it was a five-hour drive from Paris.

In the early 1990s, when Mr. Mitterrand was in his second term, the president sought to promote new figures. Mr. Hollande had won a seat in the National Assembly, and was on a shortlist to become a minister. But Mr. Mitterrand instead appointed Ms. Royal as environment minister. The president refused to have a couple, even if unmarried, in his cabinet, according to Socialist lawmaker Jean-Louis Bianco, who worked as Mr. Mitterrand's chief of staff.

In 1993, the Socialists lost control of the National Assembly, and Mr. Mitterrand was forced to pick a center-right prime minister. Like other Socialists, Mr. Hollande was sent into the opposition, where he remained stuck after Mr. Chirac won the 1995 presidential election.

The French Socialists returned to power in 1997, when Mr. Chirac's center-right coalition lost the legislative elections and the president appointed longtime Socialist Party head Lionel Jospin as prime minister. While Mr. Strauss-Kahn and other Socialist leaders got prominent seats in the new cabinet, Mr. Hollande, worried he would be confined to a junior role, chose to be head of the party. He also became mayor of the regional capital of Corrèze, Tulle, where he refurbished the historic center and organized meals for the elderly.

Mr. Chirac won a second term in 2002, thrusting Mr. Hollande into a prominent spot, chief of the opposition. But Mr. Hollande was soon criticized for his meekness and, in 2003, received a nickname from Socialist leader Arnaud Montebourg, who called him Mr. Jell-O.

"Mr. Hollande is conducting a rubber opposition," former Socialist Prime Minister Laurent Fabius said in late 2004.

"Rubber's main property is that it can bounce back," Mr. Hollande quipped in private, according to aides.

With the 2007 presidential election on the horizon, the Socialists began to prepare for the primaries. Ms. Royal disclosed her ambition to run in a gossip magazine story.

"I should have been the candidate," Mr. Hollande said in 2007. "But I thought, 'If Ségolène has more of a chance, I won't stand in her way.' "

Ms. Royal won the Socialist primaries, beating Messrs. Fabius and Strauss-Kahn, but lost to Mr. Sarkozy, 53% to 47%, in a May 2007 runoff election. The next day, she and Mr. Hollande announced their breakup.

Mr. Hollande saw his political career in tatters. He was head of a party that had lost three presidential elections in a row. "In 2007, François hit the bottom," said Ms. Trierweiler, his girlfriend.

Mr. Hollande quit the party leadership, and retreated to Corrèze. A year ago, he picked Tulle, Corrèze's capital, to announce his run for president.

© Wall Street Journal

"From here I draw the legitimacy of my commitment," Mr. Hollande said to scant media coverage. Footage showed a thinner, better-dressed man, wearing fashionable glasses - a more marketable look inspired by Ms. Trierweiler.

Close friends said Mr. Hollande, described as a bon vivant with a passion for chocolate mousse, thought being overweight would repel French voters who would think him lazy.

The initial reaction to his candidacy was apathy. Mr. Strauss-Kahn was the Socialist Party star. A year ahead of the 2012 presidential election, the IMF chief began to plot his campaign, which polls suggested would yield an easy win.

Mr. Hollande nonetheless believed he could win the primary because his low-key style was more in tune with a country hit by the financial crisis, his aides said. But it wasn't until Mr. Strauss-Kahn's arrest in New York - all charges were later dropped - that Mr. Hollande's campaign gained traction.

In June, Mr. Hollande received an unexpected boost. A TV crew recorded the conservative Mr. Chirac saying he would vote for the Socialist candidate in the 2012 presidential election.

A person close to the former president later said the comment amounted to "Corrèze-style humor." Still, the informal anointment by Mr. Chirac, who had compared Mr. Hollande to a pet 30 years earlier, gave Mr. Hollande a lift.

Late last month, Mr. Hollande went on a three-hour political show and avoided mentioning Mr. Sarkozy by name. "That's a piece of advice Mr. Chirac has given me," Mr. Hollande told reporters. "Never pronounce the name of your opponent."

Reminds me of that cynical saying about politics "Nothing happens by accicent. If it happens that way, then you can be certain it was 'planned' that way". Forget who said that, but its true.

He kind of looks a bit 'mediocre' to me, maybe that was 'planned' too?