Alvaro Munera - Make the Connection"And suddenly, I looked at the bull. He had this innocence that all animals have in their eyes, and he looked at me with this pleading. It was like a cry for justice, deep down inside of me. I describe it as being like a prayer - because if one confesses, it is hoped, that one is forgiven. I felt like the worst shit on earth."

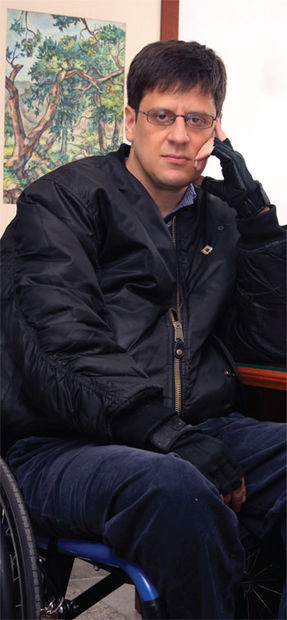

This photo shows the collapse of Torrero Alvaro Munera, as he realized in the middle of the his fight the injustice to the animal. From that day forward he became an opponent of bullfights.

Múnera became a hardcore animal rights defender and nothing less than the Antichrist for tauromachy [the art of bullfighting] aficionados. He currently works in the Council of the City of Medellín, using his position to defend the rights of disabled people and to promote anti-bullfighting campaigns.

An Ex-Bullfighter Tells His StoryA bull named Terciopelo [Velvet] gored the Colombian bullfighter Álvaro Múnera, aka "El Pilarico," in 1984, confining him to a wheelchair for life. Múnera was 18 years old back then. His best friend, "El Yiyo," was gored to death months later, and the manager of both bullfighters committed suicide three years after that.

Múnera became a hardcore animal rights defender and nothing less than the Antichrist for tauromachy [the art of bullfighting] aficionados. He currently works in the Council of the City of Medellín, using his position to defend the rights of disabled people and to promote anti-bullfighting campaigns.

Álvaro Múnera

I was born in Medellín, where my dad had taken me to see bullfights since I was four years old. The atmosphere at home was totally pro-

taurino [

taurino is the Spanish adjective for everything relating to bullfighting culture]. We didn't talk about football or any other thing, it was just bulls. Bullfighting was the center of the world for my dad. Since I grew up immersed in this

taurino atmosphere, it was logical that at the age of 12, I decided to be a bullfighter. I started my career and five years later I became successful at the Medellín Fair. This was when Tomás Redondo, who was the manager of El Yiyo, agreed to be my manager too. He took me to Spain. I fought 22 times in Spain until on September 22 of 1984, I was caught by a bull. It gored me in the left leg and tossed me in the air. This resulted in a spinal-cord injury and cranial trauma. The diagnosis was conclusive: I would never walk again. Four months later I flew to the US to start physical rehab, and I seized the opportunity to go to college. The US is a totally anti-

taurino country, and due to my former profession I felt like a criminal. I became an animal rights defender. Since then I've never stopped fighting for every living being's right not to be tortured. I hope I will continue to do so until the very last day of my life.

Did you ever think of quitting bullfighting before that bull confined you to a wheelchair?Yes, there were several critical moments. Once I killed a pregnant heifer and saw how the fetus was extracted from her womb. The scene was so terrible that I puked and started to cry. I wanted to quit right there but my manager gave me a pat on my back and said I shouldn't worry, that I was going to be an important bullfighting figure and scenes like that were a normal thing to see in this profession. I'm sorry to say that I missed that first opportunity to stop. I was 14 and didn't have enough common sense. Some time later, in an indoor fight, I had to stick my sword in five or six times to kill a bull. The poor animal, his entrails pouring out, still refused to die. He struggled with all his strength until the last breath. This caused a very strong impression on me, and yet again I decided it wasn't the life for me. But my travel to Spain was already arranged, so I crossed the Atlantic. Then came the third chance, the definitive one. It was like God thought, "If this guy doesn't want to listen to reason, he'll have to learn the hard way." And of course I learned.

Is there a lot of regret that you let it get to the point where you became paralyzed?I think it was a beautiful experience because it made me a better human being. After convalescence and rehabilitation, I started working toward the goal of amending my crimes.

Many animal rights defenders applauded your decision, but many others say they can't forgive you. They even call you "mass murderer" to this day.There are people who think that I'm just resentful for the accident. That's absurd. I've rebuilt my life and dedicated it to helping hundreds of disabled people get ahead, in addition to fighting for animal rights. On top of that, I don't know of any resentful person defending his victimizer. A bull confined me to a wheelchair and another one killed my best friend! I should reasonably be the last person on earth to care about bulls.

But as for the people who cannot forgive me for what I did to so many bulls? I have to say that I understand them and agree, to some extent. My only hope is to have a long life so that I can amend my many crimes. I wish to have the pardon of God. If He doesn't pardon me, He has good reasons not to do so.

Chiquilín, another repentant bullfighter, claims to have seen bulls weeping. He says that he cannot kill even a fly nowadays.I take my hat off to that man. He's a real hero who learned his lesson through reason and thinking.

Are you in touch with any other repentant bullfighters?Truth be told, I don't know if there are more repentant bullfighters. What is indeed known is that there are more and more ex-bullfighting aficionados every day. These are people who realized how macabre the show they were supporting really is, and so they stopped going to the bullrings. Sometimes they tell me their personal experiences and thank me for the articles I write.

What was the decisive factor that made you an animal-rights defender?When I went to the US, where I had to face an antitaurine society that cannot conceive how another society can allow the torture and murder of animals. It was my fellow students, the doctors, nurses, the other physically disabled people, my friends, my North American girlfriend, and the aunt of one of my friends, who said I deserved what happened to me. Their arguments were so solid that I had to accept that it was me who was wrong and that the 99 percent of the human race who are firmly against this sad and cruel form of entertainment were totally right. Many times the whole of the society is not to blame for the decisions of their governments. Proof of this is that most people in Spain and Colombia are genuinely anti-bullfighting. Unfortunately there's a minority of torturers in each government supporting these savage practices.

If the people of both countries are against bullfighting, why do bullfights still exist?Well, I believe that bullfighting eventually will disappear if it doesn't remove its elements of torture and death. There's a generational shift in values, and most well-educated young people are against cruel traditions.

In your articles you've associated tauromachy with a lack of culture and sophistication on the part of its aficionados. Isn't this a bit simplistic? How do you explain that intelligent people like Ernest Hemingway, Orson Welles, John Huston, and Pablo Picasso were into bullfighting?Look, to be a talented person doesn't make you more human, more sensible, or more sensitive. There are lots of examples of murderers with a high IQ. But only those who have a sense of solidarity with other living beings are on their way to becoming better people. Those who consider the torture and death of an innocent animal a source of fun or inspiration are mean-spirited, despicable people. Never mind if they paint beautiful pictures, write wonderful books, or film great movies. A quill can be used to write with ink or blood, and many terrorists and drug dealers of the 21st century have university diplomas hanging on the wall. The virtues of the spirit, that's what really counts in God's eyes.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter