© Neal N. Boenzi/The New York TimesJ. Edgar Hoover was F.B.I. director from 1924 to 1972.

The movie

J. Edgar is once again focusing attention on Director J. Edgar Hoover and the imperious way he ran the FBI for almost 48 years. Nothing illustrates that better than the case of John Dillinger.

Of all the gangsters of the era, Dillinger was the most notorious. Beginning in 1933, his gang commanded the attention of the bureau and the media with a crime spree through the Midwest. After a series of 10 bank heists, the murder of a police officer, and a holdup of a police station to obtain guns and ammunition, Dillinger escaped from jail in Crown Point, Ind.

On April 22, 1934, FBI agents received a tip that Dillinger, "Baby Face" Nelson, and other members of Dillinger's gang were at Little Bohemia Lodge, a summer resort 50 miles north of Rhinelander, Wisc. Melvin H. Purvis, the special agent in charge in Chicago, led his agents to the lodge, intending to surround it. But barking dogs gave them away.

Purvis told his men to be ready to fire. Alarmed by the commotion, three local residents who had stopped by the lodge for a cocktail ran outside and tried to drive away. In the dark, the men did not see the agents. Nor, with engines running, could they hear the command to surrender. The agents opened fire on them, killing one innocent man and wounding the other two.

Alerted by the gunfire, Dillinger and his gang escaped through the back windows of the lodge.

Everyone in the bureau assumed Purvis to be Hoover's favorite SAC. But Hoover called Purvis on the carpet, and Purvis submitted his resignation. Hoover did not accept it, but he put Samuel Cowley from headquarters in charge of the Dillinger case.

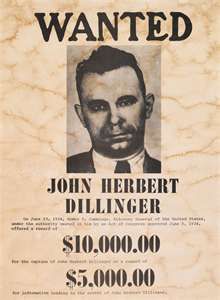

In a stroke of public relations genius, on June 22, 1934 Hoover declared Dillinger "Public Enemy Number One." Hoover increased the reward for Dillinger's capture to $10,000.

On July 21, 1934, the madam of a brothel in Gary, Indiana, told Sergeant Martin Zarkovich, a local police officer, that she would turn in Dillinger, a friend and customer, in exchange for reward money. She also asked for a halt to proceedings to deport her to her native Romania.

The officer told Purvis, who met with the madam, Anna Sage, whose real name was Anna Campinas. He verified that she indeed knew Dillinger.

Sage told Purvis that she and Polly Hamilton, a prostitute who was a favorite of Dillinger, were planning to go to a movie at one of two theaters the following night. Purvis sent agents to both theaters, and he kept an open line to Hoover. Parked outside the Biograph, Purvis saw Dillinger enter the theater with Sage and Hamilton.

To avoid harming innocent people, Purvis wanted to wait to capture Dillinger until he left the theater. At 10:30 p.m., Dillinger and the two women left the theater, and Purvis spotted them immediately. Seeing the grim-looking men in ties and white shirts, Dillinger ran into an alley alongside the theater.

"Stick 'em up, Johnny. We have you surrounded," Purvis shouted.

John Herbert Dillinger

Instead, Dillinger pulled a .380 Colt automatic from his jacket pocket. He was not able to get a shot off before three of the agents fired. They got their man.

Purvis called Hoover at home from the theater box office.

"We got him!" Purvis said.

"Dead or alive?" Hoover asked.

"Dead," Purvis said. "He pulled a gun."

"Were any of our boys hurt?" Hoover asked.

"Not one," Purvis replied. "A woman in the crowd was wounded, but it doesn't look bad."

"Thank God," Hoover said.

Hoover rushed to his office to alert the press. Asked later what the biggest thrill of his career had been, he said, "The night we got Dillinger."

Purvis talked freely with reporters about the well-executed confrontation. While he downplayed his own role and never claimed he had killed Dillinger, the press soon attributed the entire success to Purvis.

Later that year, Purvis led agents who confronted and shot "Pretty Boy" Floyd on an Ohio farm. A Hollywood studio announced that it intended to make a movie on the "man-hunting activities of Melvin H. Purvis."

Hoover was fuming, and the FBI announced that the Justice Department would not approve such a project. In Hoover's FBI, every agent was interchangeable and part of a team. Only Hoover was allowed to claim personal credit, his name always the first words in any press release. Now Purvis was Public Enemy Number One.

Because Purvis had become a hero, Hoover could not demote or fire him. Instead, he decided to make his life miserable. Hoover sent him on back-to-back inspection tours, downplayed his role in the Dillinger case to reporters, and let it be known within the bureau that he blamed Purvis for the fiasco at Little Bohemia.

Infuriated, Purvis announced his resignation from the bureau. Purvis wrote a book,

American Agent, which did not mention Hoover. It became a bestseller.

Purvis opened his own detective agency, but when Hoover put out the word that no cooperation should be given to him, law enforcement shunned him.

When Hoover learned that the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America wanted to hire Purvis, Hoover let the organization know that he would "look with displeasure, as a personal matter" at their hiring the ex-agent. If the organization wanted technical advisers, Hoover said he would supply them free of charge.

Hoover had the head of the Los Angeles office track Purvis' contacts with movie producers. When Purvis was close to landing a job, Hoover would move in with offers of free help.

In FBI personnel records, Hoover changed Purvis' departure from the bureau from a resignation to "termination with prejudice." Hoover deleted references to Purvis from official FBI accounts of the Dillinger shooting.

In 1960, after learning that he had cancer, Purvis shot himself to death with the gun agents had given him at his retirement party. After sounding Hoover out, Hoover's lieutenants sent him a memo recommending that he not send Purvis' widow a note. "Right," Hoover wrote on the bottom of the memo.

After the funeral, Purvis' widow telegraphed Hoover. "We are honored," she said, "that you ignored Melvin's death. Your jealousy hurt him very much, but until the end, I think he loved you." In the margin of the telegram, Hoover wrote to his underlings, "It was well we didn't write as she would no doubt have distorted it."

The Dillinger case and other gangster era cases such as "Pretty Boy" Floyd, Bonnie and Clyde, and "Machine Gun" Kelley showed Hoover at his best and worst. On the one hand, he built a cadre of professionals who had the intelligence, courage, and imagination to capture bad guys who had eluded local police.

Hoover tightly managed agents and provided direction that brought out the best in them. For example, just before Purvis began developing leads in the Dillinger case, Hoover wrote to him that he was "somewhat concerned" that Purvis did not seem to have underworld informants.

But Hoover's treatment of Purvis, who was most responsible for ending Dillinger's crime spree, showed what a petty, vindictive man he could be.

Ronald Kessler is chief Washington correspondent of Newsmax.com. He is a New York Times

best-selling author of books on the Secret Service, FBI, and CIA. His latest, The Secrets of the FBI,

has just been published. View his previous reports and get his dispatches sent to you free via email.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter